The Great American [Adventure] Novel

![The Great American [Adventure] Novel](/content/images/size/w1200/2025/09/960px-Albert_Bierstadt_-_A_Storm_in_the_Rocky_Mountains-_Mt._Rosalie_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg)

Last week on X/Twitter I offered some suggestions in Travis Corcoran's thread about science fiction that belongs in the canon of Great American Literature. Lots of other people I know chimed in with good suggestions, but I wanted to step back from science fiction in particular in order to explore a broader topic.

I wanted to take some time to explore the concept of the Great American Novel (GAN) through the lens of criticism. The term comes from a 1868 essay by John William De Forrest and was expanded on by Henry James in 1880. And the very first thing I'm going to do is insist that we consider stories that aren't novels as candidates.

Surely the word fiction, which, like poetry, means etymologically something made for its own sake, could be applied in criticism to any work of literary art in a radically continuous form, which almost always means a work of art in prose. Or, if that is too much to ask, at least some protest can be entered against the sloppy habit of identifying fiction with the one genuine form of fiction which we know as the novel.

–Northrop Frye, Anatomy of Criticism, Third Essay

Novel is a very slippery term in contemporary usage. It can mean any fiction story. It can mean highbrow fiction as opposed to genre fiction. It can mean a prose story greater in length than 50,000 words. I insist, following Northrop Frye, that in the context of literary criticism the novel is a genre.

Eventually I will write an essay expanding on Frye's definition, but for now what matters is much of the greatest American prose is written in the form of the romance, and limiting ourselves [often unconsciously] to novels will produce very lopsided results, systematically excluding worthy works and elevating mediocre ones that fit the limitation.

I am also interested in explicitly including low art, which overlaps with but is not wholly identical to the form of the romance. Expanding our range of consideration in this way is important because I think the essence of America, what the Great American Novel is supposed to capture, will be better served in many cases by including low art.

A lot of people, Corcoran included, feel that the term literature refers primarily to high art, but I'm using literature as a synonym for stories. It is absolutely true that some classic works have high quality prose, but I argue that many of them don't. Quality of prose is not identical to quality of story.

I would also argue that a lot of people have no real objective standard for what quality of prose really means, and so fall back on using genre as a proxy. What is really important for our purposes here is that I am willing to include stories with simple or uncomplicated prose if the story captures something unique or striking about America.

I am going to exclude poetry. Not because it is bad, but just because poetry is a different thing with different rules and the whole critical apparatus needed for poetry is badly atrophied today. Prose is now the dominant literary form, and we can jump right in by limiting ourselves to prose.

I am also going to exclude adjacent media like comics, radio, and movies. There is a lot to be said for exploring the essence of America in these forms, it is just not what I'm doing here. This is about prose fiction.

Now I'll turn to Americanness. I'm going to consider works written by Americans, without bothering to delineate that any further. There can be interesting works written about a people by outsiders, but here we are talking about how a people see themselves.

The Great American Novel is also intended to represent what it means to be American, and so of course any attempt to define it is intensely divisive and political. It shouldn't surprise anyone that prior philosophical or political or religious commitments matter here.

Rather than attempt a top-down definition of the essence of America, I think a more fruitful approach is to look for works that seem to embody Americanness, using a sliding subjective scale, and see what they imply. I think that the pattern that emerges is likely to be more interesting than one I can come up with in advance. Note that this means I'm not looking for one singular definitive story. I'm happy to embrace a plethora of works that each have something to contribute.

Let's dig into a few examples.

"Legend of Sleepy Hollow"

Washington Irving's short story from the pseudonymous collection The Sketch Book of Geoffrey Crayon might be the oldest piece of enduring American literature. I think you could probably also find some things that embody Americanness from the colonial period, but "Legend of Sleepy Hollow" stands out in part because it was written far enough from the American Revolution to be self-consciously American, and also close enough to still be reflective of that time.

Edgar Allen Poe

Edgar Allen Poe might be the greatest American author to date, so it is hard to select something specific. Especially since I excluded poetry, and Poe is probably more famous for his poetry than his prose. Poe's influence is almost too big to be reduced to a brief mention like this. Nonetheless, we might note that Poe is credited with the invention of the detective genre with his short story "The Murders in the Rue Morgue".

However, I don't think "The Murders in the Rue Morgue" is a good example of the GAN, because it is set in Paris. It deserves a mention however, because later authors developed the detective story in ways that are distinctly American. Poe's macabre gothic horror works such as "The Cask of Amontillado" "The Fall of the House of Usher" or "The Pit and the Pendulum" are formative for later writers as well, but also don't quite express something uniquely American themselves, other than how awesome Poe is. Poe spun up a bunch of new things that later writers made their own.

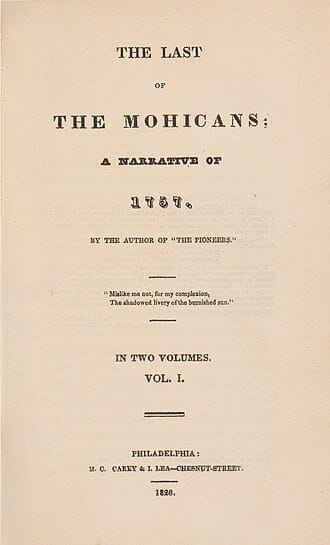

The Last of the Mohicans

James Fenimore Cooper's Leatherstocking Tales were hugely popular when written, and are also something like proto-Westerns, possibly the most American of genres. The frontier, resourceful heroes, the fraught and complicated relationship the settlers had with the native tribes, the hallmarks of the Western are here, just in an Eastern setting. Of course, at the time, Cooper's stories were about the West, it is just the West was further East back then.

Anne of Green Gables

Prince Edward Island is today part of Canada rather than the United States, but perhaps in an alternative history it could have conceivably been part of America. Anne of Green Gables is of course hugely popular, but I include it here because it is one of the purest forms of the pastoral in American-adjacent stories. The western, in its final form, is an inversion of the pastoral. But to appreciate the Western for what it is, I think we should first examine the pure form in an American context.

The Western

Westerns are foundational for American popular art because they are foundational for the American sense of self. The frontier, Westward expansion, conflicts with Native Americans and rival nations, and a scope for heroic action are a part of this very broad literature.

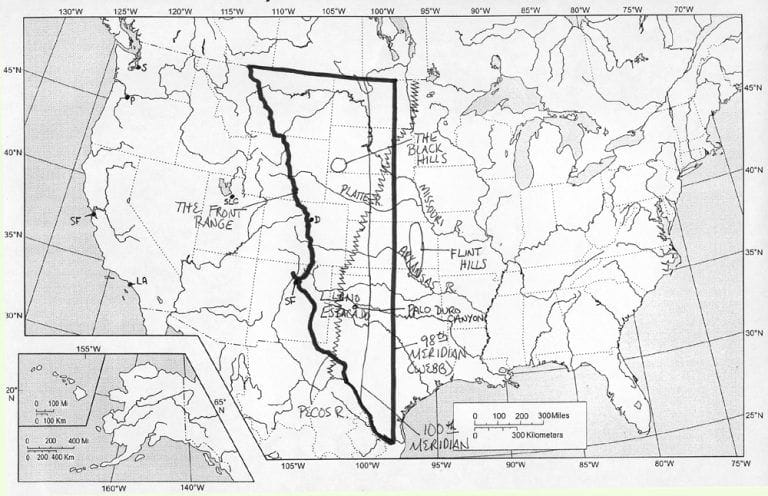

Over time, the form of the Western was shaped by the changing climate of the frontier. As you move West across the United States, the climate becomes progressively drier, and the landscape more hostile. The Leatherstocking Tales were mostly set in and around New York, except for the clearly signified The Prairie. Winters are of course famously harsh in that part of the country, but there is plenty of water. The area we typically call the Great Plains now used to be known as the Great American Desert, because the amount of rainfall wasn't sufficient for farming.

However, the vast panoramas of the plains and the jagged and dramatic features of the Mountain West are breathtakingly beautiful. The Western became a literature that expressed our love of this hostile but awe-inspiring landscape that most definitely does not love us back. Thus I say that the Western developed an inversion of the traditional form of the pastoral.

The western is largely a popular form of art, which places a primary emphasis on entertainment. I suspect that this causes the Western to be overlooked when considering the Great American Novel, unless the book is a romance hallowed by time, like the Leatherstocking Tales, or is self-consciously in the high art mode like Blood Meridian. But there are one hundred and fifty years of western stories in between those two books that I think collectively ought to be considered.

The range of stories represented by Zane Grey, Jack London, Max Brand, and Louis L'Amour might be about the most American thing possible. And we shouldn't forget the dime novels loosely inspired by Kit Carson and all the other ephemera that were enthusiastically read for more than 100 years.

The Wizard of Oz

L. Frank Baum's Oz stories were his attempt to create fairy stories that were both modern and American. The Wonderful Wizard of Oz is aimed at children, but Baum's Oz stories changed how fantastic stories were written. Baum captured something of the feel of the Midwest in his stories, and thus they shouldn't be neglected if we want a sense of what it means to be an American.

The themes that I see in Oz are the hardships of farming/ranching, a constant struggle against predatory capitalists, and a kind of homespun Midwestern morality tale in the mode of the Brothers Grimm.

The Great Gatsby

Sometimes I actually agree with the conventional GAN lists. The Great Gatsby can be seen as a critique of the very American belief that if you just make enough money, all of your problems will be solved. Despite being almost entirely set in New York, the center of gravity of the book is middle America. All of the events that follow from Gatsby's doomed love for Daisy have to be seen in the context that Nick and Daisy and Jordan and even Jay Gatsby himself are all transplanted middle Americans pursuing vain dreams in the East.

A Princess of Mars

Edgar Rice Burroughs' A Princess of Mars owes much to the Western, right down to its setting, which is much like the part of Northern Arizona where Burroughs was stationed in the Army. Twentieth century adventure fiction of all types is downstream of John Carter's escapades on Mars.

And in the real world, Burroughs was a favorite of the kind of man who made America a world leader in airplanes and rocketry.

Dune

Frank Herbert wrote one of the finest tragedies of the twentieth century, but I think part of its enduring success is that the first book is a hybrid with and a critique of the themes of A Princess of Mars. There is an intense thematic resonance with Westerns in the purity of the Fremen desert life versus the corruption of the rest of the galaxy.

A Canticle for Leibowitz

Apocalyptic and post-apocalyptic themes are common in Western literature, but A Canticle for Leibowitz is rare because it is a Catholic story with apocalyptic themes, and one of only a handful of such stories have ever been published. John J. Reilly opined that

the traditional Augustinian eschatology of the Church has long discountenanced identifying particular historical events as the unique fulfillment of scriptural prophecy. For that matter, millenarianism has even been defined as a heresy (The Catechism of the Catholic Church, Section 676). This will put a kink in anyone's creativity.

Millennial movements have long been a part of American life, and so Canticle serves as an exemplar of the form.

Last Call

Tim Powers' Last Call is the myth of the Fisher King transplanted to America. I have argued that Last Call and Neil Gaiman's American Gods are parallel novels exploring the same mimetic space, but since Powers is my favorite, I'll go with him even though Gaiman is probably better known.

Part of the magic of Last Call is the way in which Powers enculturates mythical archetypes in an American context.

Raymond Chandler

The most American form of the detective is the hardboiled detective, and perhaps the greatest example of the type is Raymond Chandler's The Big Sleep. You can tell how important the hard-boiled detective is culturally because Bill Watterson parodied it in Calvin & Hobbes.

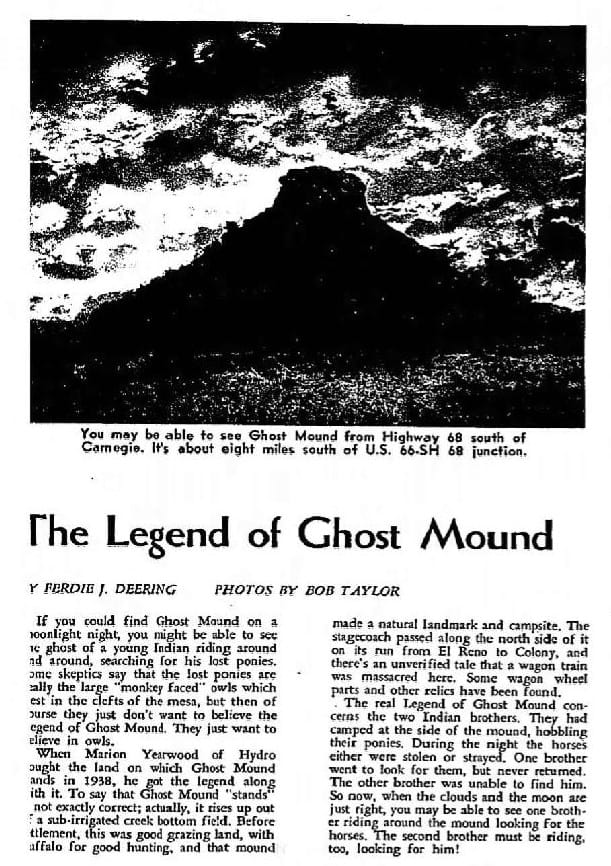

"The Mound"

Lovecraft is famous for his vision of a vast, uncaring cosmos full of indescribable horrors, but I want to zoom in on one specific story, "The Mound", because it embodies the sense that the American continent is haunted.

With the Western, the increasing physical harshness of the landscape is an important element in its development. But there is a spiritual dimension as well, with a brooding sense of watchful hostility coming from the land itself. The spread of civilization is in part the spread of institutions that suppress or contain eldritch entities.

Now that I've assembled a pile of examples, it is time to see what patterns emerge from the collected stories. I can see several slightly contradictory threads in the pile that I'm going to pull.

The first thread is that America, especially the still largely empty American West, is the natural home of Faustian Man. Oswald Spengler identified eight civilizations in his most famous book The Decline of the West. Each civilization was given a name that captured its essence. The name Spengler gave to our modern civilization was Faustian.

According to Spengler, the West is a "Faustian" civilization. Readers will recall that Faust was a legendary Renaissance scholar-magician who sold his soul to the devil in return for knowledge and power. To be Faustian is to be impatient of limits, to seek the hidden, to take terrible risks.

–John J. Reilly, Spengler's Future

There are characteristic symbols for each civilization as well. The ancient civilization of Greek and Rome was termed Apollonian by Spengler, and its symbol was the circle; perfect and eternally in the now. Faustian civilization on the other hand, is impatient of limits, oriented to the future, and its symbol is the line. In the physical world, this finds expression in the soaring skyscraper and the endlessly receding railroad. Anyone who has flown over the middle of the United States will know what this impulse looks like at scale.

Western stories are the unique American expression of Faustian civilization in a hostile landscape. But there is another aspect of the Faustian that the Western in its pure form doesn't quite express. The Second Industrial Revolution is also an achievement of Faustian Man.

Spengler's Faustian West, of course, is a being of immensely vaster scale and subtlety. Its science quite literally seeks the infinite and its technology is contemptuous of the human scale. It alone developed a mathematics which can deal with invisible forces, by means of which the West has probed the regions of the earth and of near space that have heretofore been closed not only to man, but to life itself.

–John J. Reilly, Spengler's Future

The variant form of the western that became science fiction captures our technological fascination. Burroughs is the pioneer, but later authors like Bradbury or Brackett married the conflicts of the old West with the fruits of technological progress. The Western and then science fiction were the literature of the men who first created powered flight and then took us to space.

However, in those same Westerns, there is also an anti-technological and sometimes even an anti-civilizational thread. It may be strongest in an author like Jack London; a fierce love of the land and its wildness runs headlong into the brutal efficiency and rapine nature of the extractive industries that followed the railroads into the West.

The wild and unpeopled West was seen as purer than the cities of Faustian man, which given the kind of pollution that followed the Second Industrial Revolution, is not an implausible metaphor. This strain is prominent in the non-futuristic branch of adventure stories that flowed from the Western, but Dune shows that it isn't entirely absent from the futuristic branch.

But the purity of the wilderness isn't only physical. Burroughs' Tarzan and Howard's Conan were both appalled at the corruption they saw in supposedly civilized men. Life in civilization is enervating, leading to moral lassitude on a grand scale.

Virtue is formed in the struggle against the forces of nature. The kind of man who cannot be bought or tempted is created in the plains, badlands, and mountains. But you don't spend 40 days in the desert just to deal with cattle rustlers. You go to the desert to do battle with the devil.

All the way back to Ichabod Crane, there is something eerie about the American landscape. Sometimes, it gets played for laughs like in the Disney version of that tale, but ghost stories and the American wilderness are an old old tradition. The battle to tame the West wasn't waged merely against flesh and blood, but against principalities and powers.

Taken all together, these examples suggest to me that the American character is a somewhat contradictory blend of pride in settling the American continent and disquiet at having done so. The struggle to impose Faustian civilization on the raw unformed landscape produced a very specific breed of men and women. But today's solutions are often tomorrow's problems, and the frontier turned out to be a depletable resource.

Once the frontier was closed, popular art turned to lamenting the effects of civilization on the character of Americans. I see both hardboiled detective stories and horror as an expression of this. The futuristic branch of popular art waxed a bit more optimistic at the start of the 20th century, but by the mid-twentieth century science fiction had become a literature of despair.

In retrospect, perhaps we can see this as a leading indicator of the massive loss of civilizational self-confidence that hit the Faustian civilization shortly after the middle of the 20th century.

Comments ()