A Bad Case of Dead by Jim Breyfogle

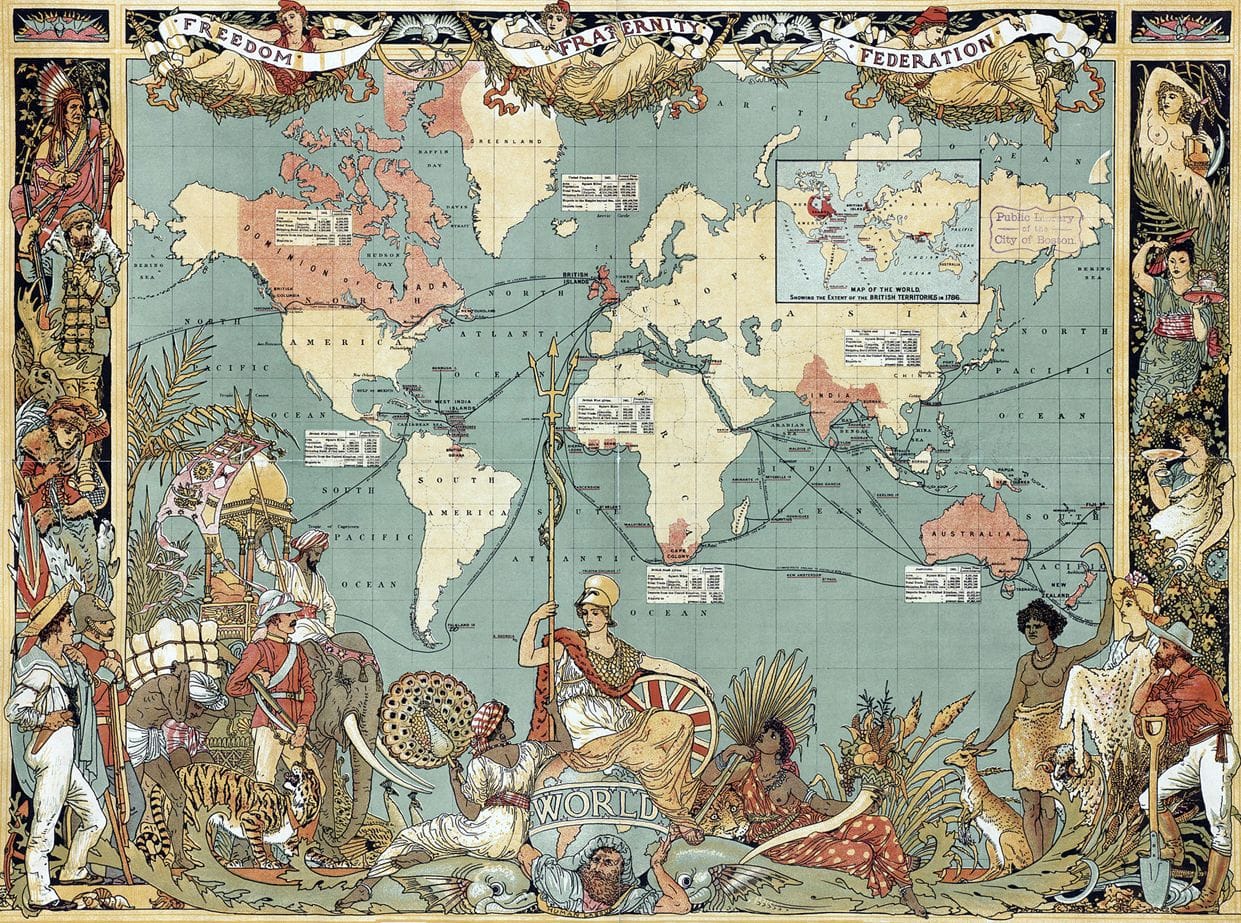

Jim Breyfogle's A Bad Case of Dead is in some ways a very traditional romance in a Victorian setting. We find a grim and dirty, but quite lively London with many economic opportunities available to the bold and the lucky. Queen Victoria's overseas dominions give Englishmen a sense of living in a much larger and more interesting world than the one they are accustomed to.

The hero Edward clerks in one of the innumerable businesses that service trade in London. He hopes to save up enough money to marry his sweetheart Rebecca, but is torn between the risk of it taking too long with his more traditional job, leaving an opportunity for some dubious gentleman to spirit her away, or the risk of not returning at all from one of the many adventures in the colonies that promise quick riches.

Yet Edward, in an extraordinary turn of bad luck, contacts a case of Dead before either of these eventualities come to pass. To save himself, he must must immediately embark on a perilous adventure not into the Wide World, but the Narrow one, where magic still lingers and Edward might find some hope of curing himself and returning to Rebecca.

At this point, A Bad Case of Dead becomes very much unlike many Victorian romances I have read. Recent Victorian adventures have tended to be Steampunk, with a profusion of brass and clockwork covering up very dull and unimaginative stories. In my experience, many authors become enamored of the trappings of steampunk and lose sight of world it symbolizes, collapsing their stories into mechanical contrivances.

The Victorian Age was a time of mechanical marvels and scientific progress. Yet at the same time, the Victorian Age was one of great faith, with fervent Christianity jostling up against alternative ways of seeing the world, spawning a profusion of esoteric philosophies and spiritualisms. This setting should readily produce a great sense of wonder, but one of the few Steampunk stories to really capture this well is Genndy Tartakovsky's Unicorn: Warriors Eternal. So many others miss the spirit of the age.

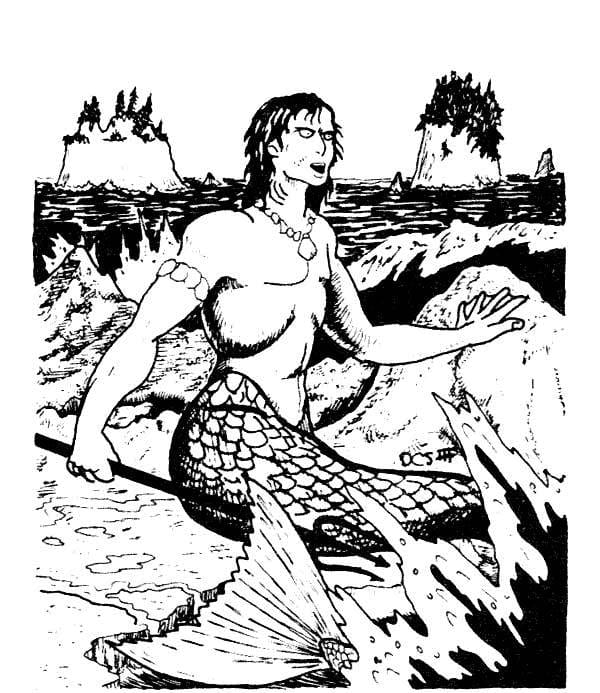

But you can go further, and A Bad Case of Dead does. A sense of the occulted and the uncanny, which Tartakovsky captured quite well, isn't enough. In the Gothic romances that spawned the penny dreadfuls of the Victorian age, there is sense of the numinous that uneasily coexists with the wild and untamed magic of the fae. While there are monsters that lurk just out of sight, there is also a sense that there are far greater perils in the Narrow world than simply being eaten in the dark.

"You have Dead, but you are Not-Dead."

"Talk sense, if you please."

"You are one of the Not-Dead, the walking corpses. A zumbi, a revenant."

Edward flinched. He had heard of the West African zumbis. "No, they are horrors, while I, I think I am feeling better."

Breyfogle's innovation is to write a zombie story, with a zombie as the hero, that retains a human perspective. Zombie stories enjoyed a great vogue fifteen or twenty years ago, but stylistically they all suffered from the mindlessness of the zombie. The themes you can explore with zombies as the primary element of horror can be limited. As John J. Reilly noted on All Hallows Eve in 2007:

Vampires are evil (or penitent) and werewolves have pathos, but zombies are just meatpuppets. They do not imply a moral universe.

The usual setup for a zombie story has plenty of horror, but the zombies themselves are simply a mechanism for that horror. A character may be bitten, die, and turn, but the end is certain. Breyfogle has found a way to manufacture a greater narrative space within a zombie story by making his hero into one, but granting him an interlude within which he can attempt to avert his fate:

Undulark rose and walked into the next room. Glass clinked and he returned with a dark bottle. He held it up to the light and swirled it, and shook his head. "Wrong bottle," he muttered and left the room again. He did this twice more before handing the bottle to Edward. "If you drink this, it will slow the process."

The bottle nestled in Edward's palm. It was an odd size, more than half a pint, less than a full one. It felt solid; either it contained a heavy liquid, or the black glass was thick. "How long?"

"You don't need much, so quite long. Six months perhaps, before you start to see any real effects of Dead. Then Dead starts to take over."

The narrative is relentlessly driven by Edward's desperate attempt to find a way to cure his case of Dead and return to Rebecca. Breyfogle's pacing emphasizes for the reader Edward's mounting dread and anxiety, throwing Edward into action and never giving the reader time to ruminate on Edward's condition. Instead, Edward and the reader alike must simply respond to events has they occur and hope against hope that some solution might be found before Edward's time runs out.

This rapid pacing is supported by a panoply of remarkable characters. Edward meets many people on his journey, some unaccountably helpful, some indifferent to his fate, and others who would do almost anything to harm Edward. Edward's interactions with the denizens of the Narrow world give the book considerable depth from a wide variety of brief encounters.

Each character, even relatively minor ones, feels like they have a story of their own, which Edward only briefly interacts with, granting a satisfying illusion of a living world. That living world, in combination with the sense of the numinous that lurks just out of sight, gives this zombie story a moral universe so unlike the many many examples that inspired John Reilly's comment.

Because for Edward, there are far worse fates that could befall him than turning into a mindless killer. His choices matter, even though he is in extremis almost from the first page. That is what gives this story a heart, and makes it worth a read.

I was given a review copy of A Bad Case of Dead by the publisher

Buy A Bad Case of Dead from Amazon

Comments ()