Timothy Zahn's Quadrail Series

I recently finished a re-read of Timothy Zahn’s Quadrail series. My first time was in 2018, and I was curious how well this mystery-like science fiction would hold up once I already knew whodunit. As it turns out, just about as well as the first time, maybe even a few things were better.

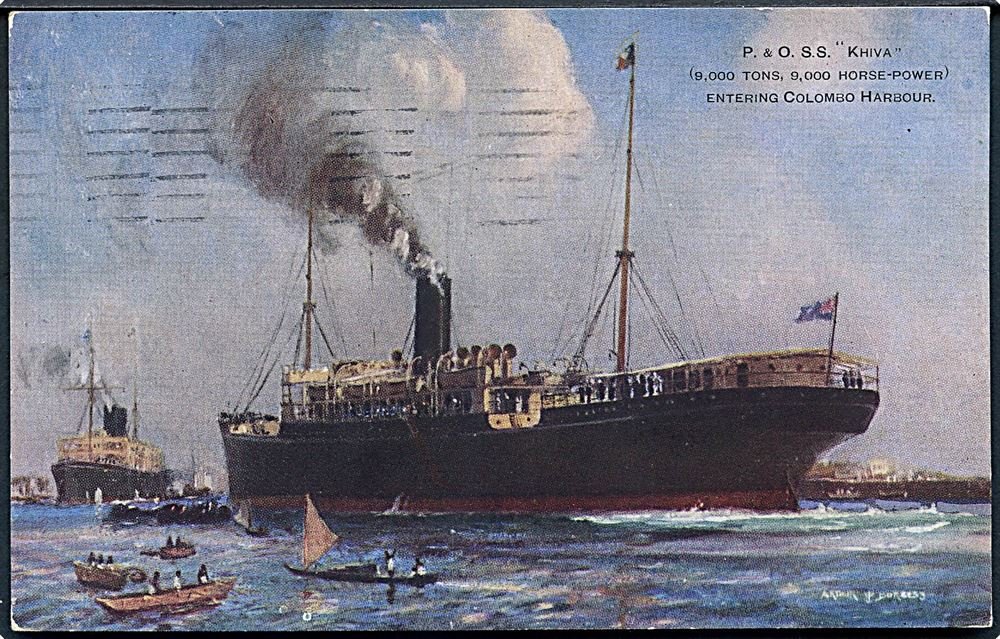

I have to guess that Zahn had a lot of fun writing the Quadrail series, which is very much Murder on the Orient Express, in spaaace! When I talk about Zahn writing things that wouldn’t meet Campbelline standards, the trains in space method of interstellar travel that Zahn invented for this series probably drives hard scifi purists nuts, but it produces a really neat setting, so who cares?

If you can get past the idea of trains between the stars, Zahn’s ability to build a self-consistent setting really shines. In some science fantasy, futuristic technology serves as nothing but a vehicle for moving the plot wherever the writer wants it go. This can be fun, but I do think that some of the most interesting works that are now called science fiction do what Campbell pushed for, taking an idea and extrapolating it into the unknown.

In Quadrail, the only way to move people and goods around the galaxy is on the Quadrail system, controlled by the mysterious Spiders. The Spiders enforce a kind of pan-Galactic status quo, limiting the movement of major weapons to only recognized governments, and strictly curtailing any kind of dangerous object in their train system. In general, messages move faster than people, due to a telegraph like message system the Spiders run along the tracks, but you still need to get the message from the station, providing interesting dynamics that everyone must account for.

In this case, what Zahn has done is take the feel of a late-nineteenth to mid-twentieth world connected mostly by ships and rails but with the border stasis of the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, and then create a secret battle of assassins to see who will control the transportation network, and thus the fate of the entire galaxy. Oh, and the players all feel like they come from a late Cold War espionage milieu, minus the threat of nuclear war. A real wilderness of mirrors where you cannot trust anyone but the stakes are immense.

Early Tom Clancy feels a lot like the Quadrail, with the protagonist, Frank Compton, being the kind of highly competent spook that Jack Ryan was. Compton can fight, and fight well, but he is an exceptionally devious and resourceful man. His real weapon is his mind, which is top-notch. He is also a prickly and difficult man, which is why at the beginning of Night Train to Rigel, he is a former intelligence agent who has no friends, having burned every last bridge in the act that got him cashiered.

The psychological portrait of Compton alone is probably worth the price of admission. Anyone who has thought deeply about outsized success in the modern world is familiar with the strange personalities that loom behind every major accomplishment. However, most of the time people are apt to think of autists, and Frank Compton is not an autist. He is far too good at understanding his enemies from the inside. He is more like Steve Jobs, a sociopathic empath, exceptionally skilled at manipulating others by understanding them better than they understand themselves. Except instead of being the world’s greatest salesman, Compton is the galaxy’s greatest investigator, motivated by a kind of grumpy and lonely integrity that cares nothing for the opinions of others.

Compton, as a master spy, also has a kind of moral callousness that shocks. It is not that he cannot feel, for he understands the feelings of others far too well. He is simply ruthlessly focused on the ultimate goal, too logical not to sacrifice a piece when the game calls for it. It’s no wonder no body likes him, even when he’s right.

And so, like a lot of men who have made violence their profession in the name of the good, the only people who really understand and appreciate Frank Compton are his enemies, or maybe perhaps a few fellow practitioners of the art of instrumental aggression. Tim Zahn isn’t as great as Cole and Anspach are at getting you into the head of the rough men who stand ready to do violence while you sleep in your bed, but he does understand that one of the few people in the galaxy likely to see Frank Compton for who he truly is would be a special forces operator of another species.

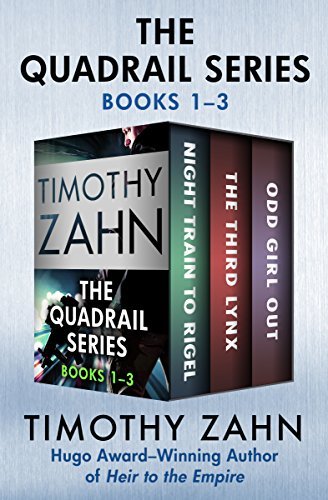

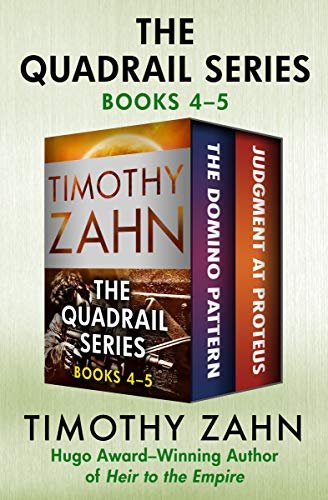

The series as a whole wraps up its interstellar conflict in five volumes. A respectable length, but not drawn on too long. I almost wonder whether Zahn might have initially planned something else, as the fifth book is about half again as long as any of the others, but the story hangs together pretty well in the last one, perhaps the most exciting volume, so maybe he just needed a little more space to do the story justice.

A little patience can get you a sale on the two collections of ebooks that this series is broken up into, often for less than $5 each. I think that patience should be rewarded.

My other book reviews | Reading Log

Other books by Timothy Zahn

New Thrawn series:

Thrawn

Thrawn: Alliances

Thrawn: Treason

Quadrail series:

Night Train to Rigel: Quadrail book 1 review

The Third Lynx: Quadrail book 2 review

Odd Girl Out: Quadrail book 3 review

The Domino Pattern: Quadrail book 4 review

Judgement at Proteus: Quadrail book 5 review

Original Thrawn Trilogy:

Heir to the Empire

Dark Force Rising

The Last Command

Blackcollar series:

The Blackcollar: Blackcollar series book 1 review

The Backlash Mission: Blackcollar series book 2 review

Dragonback series:

Dragon and Thief

Dragon and Soldier

Dragon and Slave

Dragon and Herdsman

Dragon and Judge

Dragon and Liberator

Comments ()