The Long View 2006-11-20: Steyn, Tesla, and Option Two

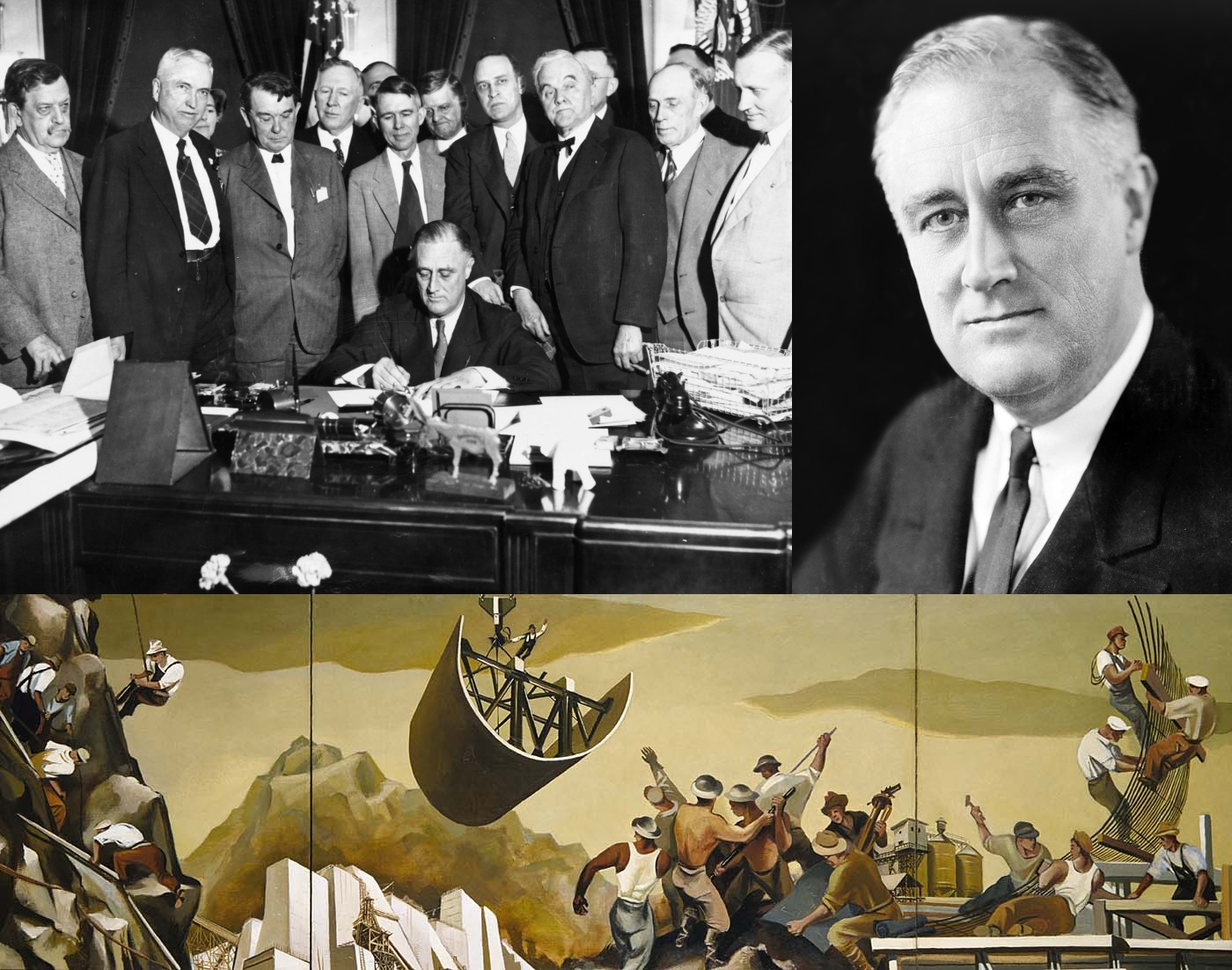

By LordHarris at English Wikipedia - Top left: (from here)Top right:(from here)Bottom:(from here).Transferred from en.wikipedia to Commons by Pass3456., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=17002806

Here is an interesting reflection on social democracy. In the United States, it is a relatively common political position on the Left to advocate for some kind of social democracy, with some people being confused, thinking this is a variety of socialism, or even communism. In history, social democracy has been inseparable with nationalism, which provided the power to execute on ambitious social projects and the social cohesion necessary for success.

Option One is to recondense the social democratic state of the earlier 20th century. A necessary part of that project would be to dismantle the social-consumer state of the last third of the century, which actually produced the pathologies that Steyn deplores.

Option Two would require the judgement that social democracy is now anachronistic. A.J.P. Taylor remarked that one of the consequences of the First World War was that the fate of the English people and of the English state merged for the first time: that merger was "social democracy." The second option, then, would be to undo that merger in every advanced country. In the 18th century and in prior times the state was not that much more prominent than other corporate bodies. Government was the business of elites. The difference between civilized and barbarous states was that, in the civilized ones, government had reached a truce with civil society. People were allowed to go about their business without the need to worry much about what their "country" was doing. The survival of the state did not depend upon the patriotism of the population. Option Two is to reestablish that condition.

This observation dovetails nicely with the theory that we are due for the formation of a universal state sometime late this century. One of the reasons that nationalism has a bad reputation is that the need for social cohesion and the stakes of the struggle genuinely resulted in oppression. What usually isn’t taken into account is that social safety nets, environmental and workplace regulations, and civil rights were enforced upon recalcitrant minorities and dissenters as well, using the increased state power that nationalism made possible.

The minimalist states of the eighteenth century could never have done any of these things. It is possible that the states of the twenty second century will not be able to either.

Steyn, Tesla, and Option Two

Late modern monuments are usually appalling, but Mark Steyn finds some more appalling than others:

On the tomb of the great architect Sir Christopher Wren at St Paul’s Cathedral is a famous inscription: si monumentum requiris, circumspice; if you seek my monument, look around.” Conversely, if you’re seeking the tomb of western civilization, look around at the monuments. Not the old ones to generals and potentates, but the new ones. ...

Sharing the heart of the capital with King George IV, General Sir Charles Napier and Major General Sir Henry Havelock these days is Alison Lapper, an armless woman heavily pregnant. At the unveiling, Miss Lapper said the new statue would force Britons to “confront their prejudices” about disability...

Another monument: the Arizona 9/11 Memorial. It is a remarkable sight. ...the Arizona memorial is an almost parodic exercise in civilizational self-loathing, festooned in slogans that read like a brainstorming session for a Daily Kos publicity campaign: “You don’t win battles of terrorism with more battles.” “Foreign-born Americans afraid.” “Erroneous US airstrike kills 46 Uruzgan civilians.” And this is the official state memorial.

A third monument, a third country: France. This one was unveiled at the end of October in Clichy-sous-Bois. If that name rings a bell, it’s the bell on the fire truck racing through the streets to douse the flaming Citroens and Renaults in last year’s riots....Clichy-sous-Bois has put up a monument to the unfortunate Zyed Benna and Bouna Traore...

[I]f these monuments truly represent the spirit of each nation as those monuments to Nelson and Napier did in their day then you would have to be an unusually optimistic sort to bet on the long-term prospects of all three countries.

In Ayn Rand's The Fountainhead, I believe, a character remarks on a bestselling autobiography by someone who had spent a lifetime doing nothing more than holding a routine job and chatting with neighbors: in such a cultural climate, the character explains, the fact that someone else has designed an excellent cathedral becomes invisible and unreportable. I wonder whether that is actually true: we can usually distinguish between important public figures and mere celebrities. However, it is true that new public monuments have become like cable-television stations: some have merit, but they are pitched to a niche audience, like the old broadcast television networks were. So, to some extent, the phenomenon is just another consequence of the evaporation of the mass public of the first half of the 20th century. The question is whether we want to recondense that mass.

The 911 monument that Steyn abhors really is just an other example of the general principle that modern monuments are almost invariably designed to reprove rather than to unify. This is not a defect of national spirit, I suspect, but of a lazy arts establishment.

* * *

The reply of 38 Muslim scholars to Pope Benedict's Regensburg Address has already been discussed on this blog. Here is a rather less temperate criticism of the reply, from Islam Watch. Readers may find it interesting for its account (a rather jaundiced one) of the early days of Islam, but it is too angry and diffuse to be an effective polemic.

* * *

So you thought Nikola Tesla was mad, mad, did you? Well, he may well have been, but he seems to have been right about broadcast power:

US researchers have outlined a relatively simple system that could deliver power to devices such as laptop computers or MP3 players without wires....

The answer the team came up with was "resonance", a phenomenon that causes an object to vibrate when energy of a certain frequency is applied.

"When you have two resonant objects of the same frequency they tend to couple very strongly," Professor Soljacic told the BBC News website...the team's system exploits the resonance of electromagnetic waves. Electromagnetic radiation includes radio waves, infrared and X-rays.

Typically, systems that use electromagnetic radiation, such as radio antennas, are not suitable for the efficient transfer of energy because they scatter energy in all directions, wasting large amounts of it into free space.

To overcome this problem, the team investigated a special class of "non-radiative" objects with so-called "long-lived resonances".

When energy is applied to these objects it remains bound to them, rather than escaping to space. "Tails" of energy, which can be many metres long, flicker over the surface.

"If you bring another resonant object with the same frequency close enough to these tails then it turns out that the energy can tunnel from one object to another," said Professor Soljacic...Nineteenth-century physicist and engineer Nikola Tesla experimented with long-range wireless energy transfer, but his most ambitious attempt - the 29m high aerial known as Wardenclyffe Tower, in New York - failed when he ran out of money.

Broadcast power used to figure occasionally in science fiction, since you needed it to power the flying cars. The MIT project is not so ambitious. Still, I wonder whether this might have some application to, say, the Space Elevator. There is the lift question, for one thing. Also, magnets that don't need cables could come in handy in other ways.

* * *

Getting back to the condensation issue, Mark Steyn laments the rift in the Republican Party between the Win the War faction and the Small Government faction. He reasons thus:

I support the Bush Doctrine on two grounds -- first, for "utopian" reasons...second, it also makes sense from a cynical realpolitik perspective: Promoting liberty and democracy, even if they ultimately fail, is still a good way of messing with the thugs' heads...The president doesn't frame it like that, alas. Instead, he says stuff like: "Freedom is the desire of every human heart." Really?...The story of the Western world since 1945 is that, invited to choose between freedom and government "security," large numbers of people vote to dump freedom -- the freedom to make your own decisions about health care, education, property rights, seat belts and a ton of other stuff...If ever there was a time for not introducing a new prescription drug entitlement, wartime is it. Yet the president and Congress apparently decided that they could fight a long existential struggle abroad while Big Government continued to swell and bloat at home. ...Someone in the GOP needs to do what Ronald Reagan did so brilliantly a quarter-century ago: reconcile the big challenges abroad with a small-government philosophy at home. The House and the Senate will not return to Republican hands until they do.

This is an odd reading of the post-World War II West. While perhaps our right to drive without seat belts has been alienated from us, can we really be said to be less free in a world in which censorship has been almost entirely abolished? Conversely, perhaps the most odious thing about the health-care regime in the United States has been its evolution into a system that turns people into the indentured serfs of unsatisfactory employers.

I can only repeat: the expanding welfare state (well, welfare-and-regulation states) was characteristic of the participants in the world wars. Their establishment was part of the defense effort, even during the lulls between the wars, when people did not realize that war was what they were preparing for. Let me put it this way: socialism is war by other means. At least in the years from 1865-1945, the ability to wage an existential struggle abroad presupposed more welfare-and-regulation at home.

If there is another existential threat, there are just two options to deal with it.

Option One is to recondense the social democratic state of the earlier 20th century. A necessary part of that project would be to dismantle the social-consumer state of the last third of the century, which actually produced the pathologies that Steyn deplores.

Option Two would require the judgement that social democracy is now anachronistic. A.J.P. Taylor remarked that one of the consequences of the First World War was that the fate of the English people and of the English state merged for the first time: that merger was "social democracy." The second option, then, would be to undo that merger in every advanced country. In the 18th century and in prior times the state was not that much more prominent than other corporate bodies. Government was the business of elites. The difference between civilized and barbarous states was that, in the civilized ones, government had reached a truce with civil society. People were allowed to go about their business without the need to worry much about what their "country" was doing. The survival of the state did not depend upon the patriotism of the population. Option Two is to reestablish that condition.

Certain necessary features of such a regime are immediately obvious, such as a genuinely mercenary military. Also, tax revenues would have to be raised from more narrowly defined, institutional sources: levies on individuals would have to almost disappear, lest the taxpayers ask what their money was being used for. By the same token, popular control over government expenditures would have to be limited, since otherwise the electoral franchise would become just a license to spend other people's money. Option Two, in fact, would be very like the universal implementation of "petrolism," the sort of regime we often find in oil-producing countries where the government is funded by petroleum revenues and does not need to levy taxes domestically.

All this has current or historical precedent, and could be made to work. The one question is what motive the rulers of such a system would have for maintaining the societies from whose interests they had been at such pains to divorce themselves.

Copyright © 2006 by John J. Reilly

Comments ()