L. Sprague de Camp and Literary Convention

Twitter/X user The_Lord_Otter recently opined that L. Sprague de Camp was instrumental in preserving and promoting the work of Robert E. Howard, but that de Camp's own work was merely okay. I endorse this view, but I wanted to take a tangent into what I think de Camp was really good at doing in his stories.

de Camp was a heavy user of explicit literary convention, in an era which has often gone to great lengths to disguise conventions.

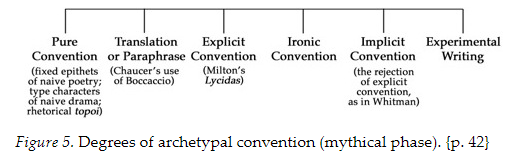

All art is equally conventionalized, but we do not ordinarily notice this fact unless we are unaccustomed to the convention. In our day the conventional element in literature is elaborately disguised by a law of copyright pretending that every work of art is an invention distinctive enough to be patented. Hence the conventionalizing forces of modern literature - the way, for instance, that an editor's policy and the expectation of his readers combine to conventionalize what appears in a magazine - often go unrecognized. Demonstrating the debt of A to B is merely scholarship if A is dead, but a proof of moral delinquency if A is alive. This state of things makes it difficult to appraise a literature which includes Chaucer, much of whose poetry is translated or paraphrased from others; Shakespeare, whose plays sometimes follow their sources almost verbatim; and Milton, who asked for nothing better than to steal as much as possible out of the Bible.

–Northrop Frye, The Anatomy of Criticism, Second Essay

Northrop Frye posited a range of literary convention, from rigidly fixed forms and types to work that avoids established patterns. From the twentieth century on, literary convention has largely shifted to ironic or implicit convention, partly spurred by copyright law, but also simply by a shift in literary fashion that emphasizes uniqueness and individual authors.

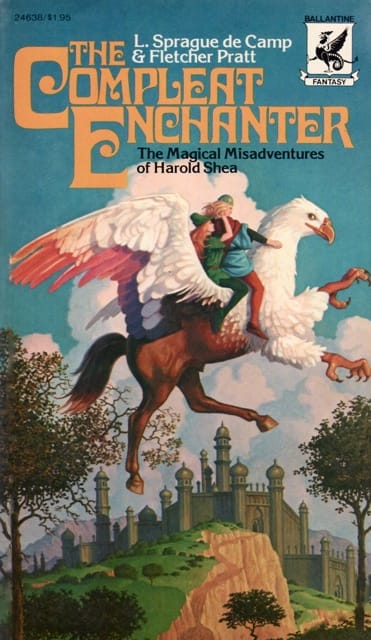

de Camp stands out to me as an author who was willing to make his conventions explicit. Let's start de Camp's collaboration with Fletcher Pratt, the Compleat Enchanter.

When Harold Shea magics himself out of his unsatisfactory mid-century life into fantastical adventures, he ends up in worlds that are recognizably those of the prose Edda, Spencer's the Faerie Queene, Horace Walpole's the Castle of Otranto, Ludovico Ariosto's Orlando Furioso, and Samuel Taylor Coleridge's Kubla Khan.

de Camp and Pratt are in conversation with all of those earlier works, but also telling their own story. As you might guess from the subtitle, Shea is a hero in the ironic mode: things mostly do not go the way he wants them to. The story is written in the idiom of its time, but probably served as an introduction to those other, greater stories to a great many genre readers.

Next, let us consider Lest Darkness Fall. de Camp's story of a modern man thrown back in time is in conversation with Mark Twain's A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, but not simply an imitation of that. Twain's book is a satire, with the books [or perhaps the audience] of Sir Walter Scott as a likely target. While de Camp is also engaged in a demythologized portrayal of the past, Lest Darkness Fall is firmly in the fannish technologically-oriented mid-twentieth century science fiction oeuvre.

de Camp did a great job of making these kind of literary links explicit, which I see as something that elevates his work above his plots, themes, and characters. I'm not greatly familiar with all of de Camp's output, but I do find that there is a kind of similarity in Harold Shea and Martin Padway. Specifically, they both strike me as massive nerds. The kind who got shoved in lockers.

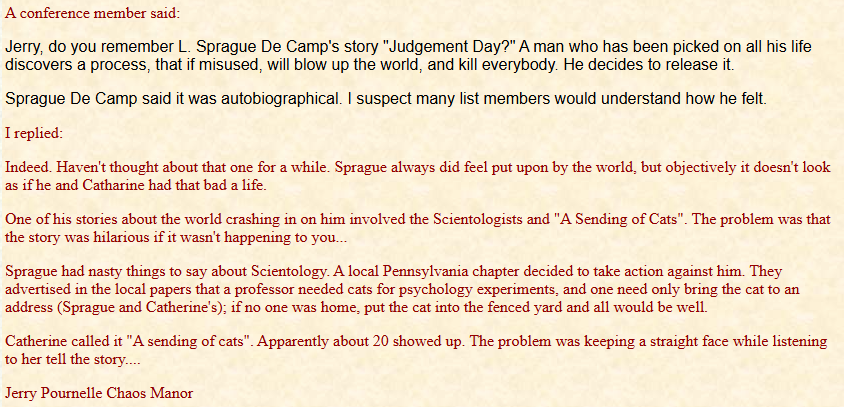

Which brings me to a funny story from Jerry Pournelle about the de Camps. A correspondent wrote to Jerry asking about de Camp's short story "Judgment Day", which is a nerd revenge tale.

Jerry said that Sprague felt "put on by the world". I think that I can see some of that coming through in the characters and themes of the stories by de Camp that I have read. The anecdote that Jerry relates is objectively pretty funny, and I can guess that neither Sprague nor his wife found it funny at all. A man with a different character might have shrugged it off, but Jerry is giving this as an example of how de Camp viewed the world. This all seems pretty consistent to me.

If you don't have that kind of a point of view, de Camp's work may not resonate strongly. But, I do want to give de Camp some credit for what he accomplished. Since de Camp is not my favorite author, I haven't read even a tenth of his prodigious output. I invite comments from anymore deeper in his corpus.

![The Great American [Adventure] Novel](/content/images/size/w720/2025/09/960px-Albert_Bierstadt_-_A_Storm_in_the_Rocky_Mountains-_Mt._Rosalie_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg)

Comments ()