The Last Fanatics: How the Genre Wars Killed Wonder

The Last Fanatics by JD Cowan is an important piece of unaffiliated but not wholly unrespectable scholarship about the history of science fiction, fantasy, and horror in the twentieth century. No one else is asking, let alone answering the question of how we got here with the amount of detail you can find in this book.

The Last Fanatics: How the genre wars killed wonder by JD Cowan July 7, 2022

Cowan’s book is a re-discovery and a synthesis of five important sources that document how we got to where we are now:

Sam Lundwall’s Science Fiction: An Illustrated History

Cheap Thrills: An Informal History of the Pulp Magazines by Ron Goulart

Science Fiction: What it’s all About by Sam Lundwall

The Immortal Storm: A History of Science Fiction Fandom by Sam Moskowitz

The Open Conspiracy by H. G. Wells

Lundwall’s two volumes are pure distillations of the point of view of what Cowan calls Fandom, and I just prefer to refer to as fanatics: the inward-looking gatekeepers who created science fiction in the 1930s and whose intellectual descendants continue to police it. Lundwall wasn’t there at the beginning, but he is a true believer in the cause. Critically, Lundwall’s books were commissioned by Donald A. Wollheim, who was there in the beginning and was a very influential author and editor. Goulart’s book is a necessary corrective to the other four, as it explains in detail what the pulps, popular literature of the beginning of the twentieth century, were really like. Lundwall in particular defines his ideal kind of science fiction against the pulps. Moskowitz’ book is the ultimate insider account from the very beginning, revealing the coterie of letter-writers that coalesced into Fandom. Wells was not directly involved in the American fanatic scene, but their accounts make it clear that he served as a guiding light for what they were trying to do.

Essays on each volume are available on Cowan’s website, but this book is an expanded version that explicitly ties it all together. I will address this compilation as a cohesive argument about the reason for the long decline of genre fiction in the twentieth century, as I believe it to be one that is worthy of wider consideration.

The real power of Cowan’s work is that it allows us to read about the calamity that befell genre fiction in the twentieth century in the words of the people who did it. They will tell us what they did and why. Cowan is of course here to tell us why they should have not.

Cowan’s thesis is that a small group of committed ideologues created science fiction [and fantasy and horror] by intentionally dividing a previously unified genre. This tends to strike contemporary readers as an odd thing to say. We all know what science fiction and fantasy and horror are, why would you try to conflate them?

But of course we don’t actually know what they are. Arguments over what science fiction is, and what is in and what is out, are hilariously commonplace. There are few easier ways to start a serious fight on social media with avid readers than to try to provide a definition and mark popular works as in or out. No one ever fights about what mystery is, or what romance is. It is so obvious that once you know what the term means, a book is easily classified. Only science fiction is different.

Cowan uses Lundwall’s own summaries in Science Fiction: An Illustrated History and Science Fiction: What It’s All About of the various attempts to define science fiction between the 1850s and the 1970s to argue that the real problem is that the people who wanted to define science fiction cannot, because they are not actually defining a genre at all.

"Even though the origins of science fiction go back to the mid-19th century, nonetheless as a new literary genre, charged with special social functions, science fiction is the undoubted product of the nuclear age. The more meaningful the scientific and technological breakthroughs and their impact on modern life, the greater the role of science fiction, stimulating our vision for things to come, especially in the aspect of the changes wrought in man's mentality by the scientific and technological revolution. Science fiction brings home the awareness that the future will continue to bring radical changes in all areas of man's life; science fiction is there to prepare him for this eventuality." — Elka Konstantiova

"Science fiction is a branch of fantasy identifiable by the fact that it eases the 'willing suspension of disbelief on the part of its readers by utilizing an atmosphere of scientific credibility for its imaginative speculations in physical science, space, time, social science and philosophy." — Sam Moskowitz

"Science fiction is what you find on the shelves in the library marked science fiction." — George Hay

"Science fiction doesn't exist." — Brian W. Aldiss

Science fiction doesn’t exist.

The first and longest is clearly Lundwall’s preference. Cowan’s preference, and mine, is the shortest. Most readers, and even most authors, simply use the shelf label definition, because it’s easy. Let’s see what Cowan has to say about what a genre is to clear things up:

The larger point is that none of this describes the purpose of a genre.

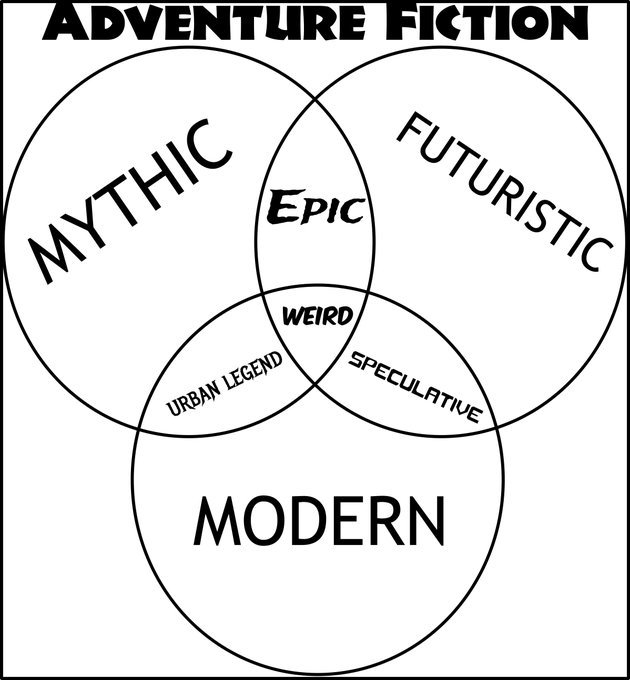

Unlike, say, Mystery which is about mystery, or Romance which is about romance, or Adventure which is about adventure, if your genre requires mental gymnastics to explain to a child then it is not sharply defined. One sentence should be enough. Genres aren't aesthetics or themes; genres are defined by what emotion and sensation they are meant to invoke in the reader. This is why the average reader picks up a book to begin with. They choose one based on the experience it will give them.

What the above writers are fumbling around to define is Wonder. It is the adventure of exploring new lands, peoples, and possibilities. Pair that with the fairy tale and Marchen origin and you will see where I am going with this, and why the battle for an original definition has been fruitless for well over a century. It's never going to have one, and that is a point that should be discussed more than it is.

Cowan focuses on Wonder as the emotion that defines the real genre here. Stories that we call science fiction and fantasy and horror can all fall within it. However, it is important to note that just because a contemporary story might be shelved as science fiction, that doesn’t make it a wonder story. Many such stories have been written to exclude a sense of wonder. Cowan suggests that is why they sell so poorly, and I would agree with him.

When a science fiction or fantasy or horror book sells well, it is almost always an adventure, if marketed to men, or a romance in the modern sense, if marketed to women. The ones that don’t sell well are something else entirely.

Wonder stories

So why did the fanatics break apart wonder stories into different categories? It starts with the Second Industrial Revolution. Lest that seem grandiose, that I mean is that the 1920s and 1930s really were the pinnacle of scientific and technological achievement in the United States. The very real technological marvels of this age gave science fiction its optimism and belief that the future would be fundamentally unlike the past.

This period also coincided with the peak of popularity for pulp fiction. Goulart says in Cheap Thrills:

"The pulps sold cowboys, detectives, lumberjacks, spies, Royal Canadian Mounted Police, sandhogs, explorers, ape men, aviators, phantoms, robots, talking gorillas, boxers, G-men, doughboys, spacemen, Foreign Legionnaires, knights, crusaders, corsairs, reporters, Masked Marvels, ballplayers, doctors, playboys, pirates, kings, stuntmen, cops, commandos and magicians—usually for ten cents and never for more than twenty-five cents."

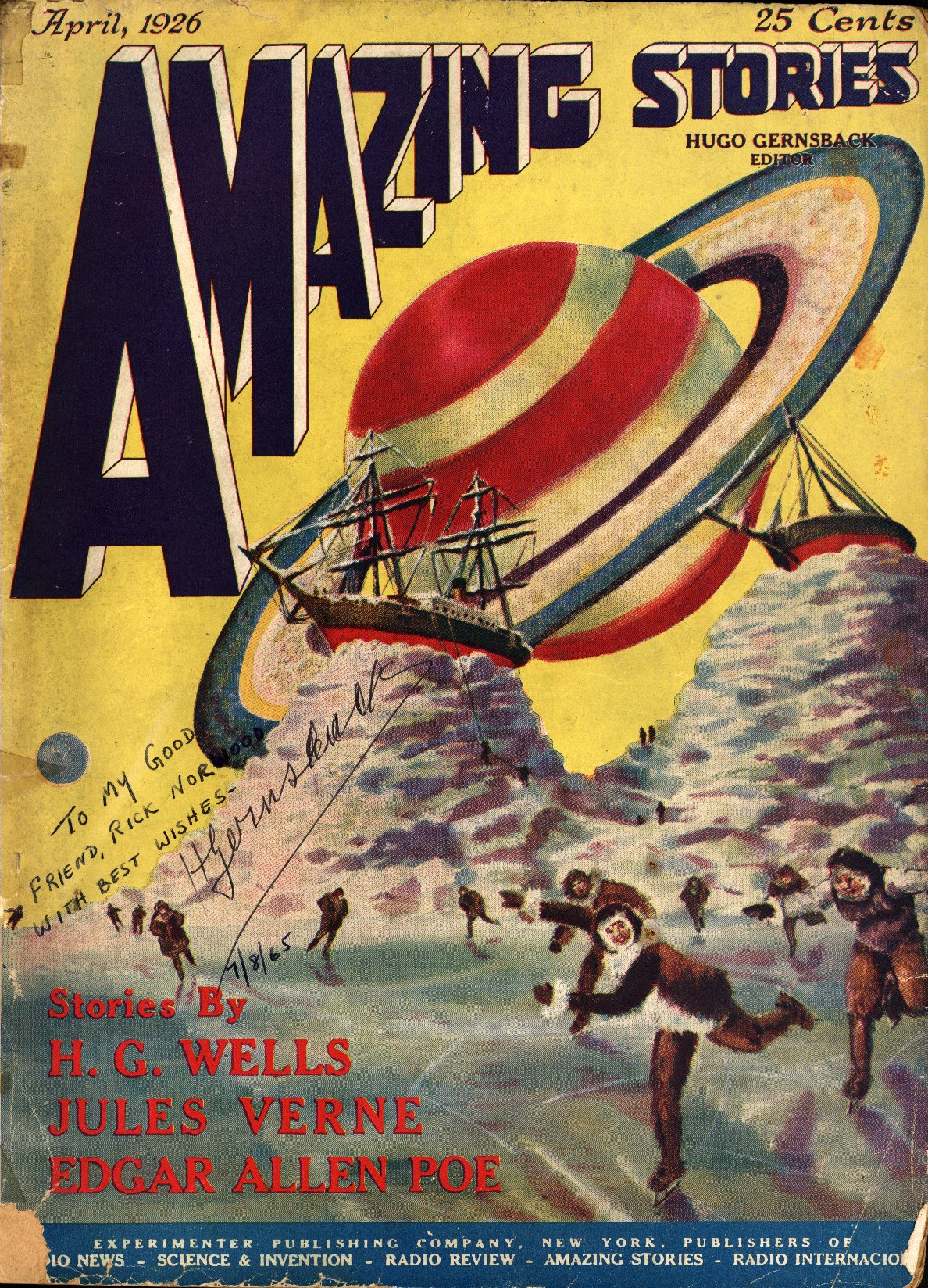

In this environment, clubs of like minded individuals formed on many and diverse topics, including many scientific ones. Science hobbyists loved science, and a man named Hugo Gernsback had some success fusing his science hobby with a pulp magazine called “Amazing Stories”.

The first issue of Amazing Stories

By Unknown author - see above, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=10503159

The early fanatics were formed by an alliance of science hobbyists and people who were into the fiction, the actual origins of the term “science fiction”. But over time, feuds and rivalries pushed the science enthusiasts out. Moskowitz’ book is hugely valuable in laying all this history out. One of the last science enthusiasts standing was a man named William Sykora, and he said this when he resigned from the International Scientific Association he had founded, a science enthusiast club that was eaten up in backroom wrangling over who would really be in charge:

“Scientifiction is only a means to an end, a bit of writing or a story that would make the reader want to get into the thick of the fight man is waging in his effort to better understand nature and life. But scientifiction, far from being the stimulus to scientific study it should be, had become an end in itself... a sort of pseudo-scientific refuge for persons either incapable of pursuing a technical career, or else too lazy to do so.”

Of course, people who actually just loved science could still be members of the Telescope Maker’s Society, or any of thousands of groups just like it that existed at the time. Sykora, like Gernsback, wanted to use the stories as propaganda to get people into science. That is how he got involved with the fanatics in the first place, because they also wanted to propagandize. The fanatics just won the battle for control and pushed Sykora out.

So what did the fanatics want? Here, I think we should turn to John B. Michel’s famous Mutation or Death speech, given in October of 1937, about six months after Sykora was cast out of his own club. Michel’s work is so definitive that for a while this set of ideas was just called “Michelism”, but eventually the group he was in took to calling themselves a more aspirational name that you might know: the Futurians.

Futurians. Left to right: Cyril Kornbluth, Chester Cohen, John Michel, Robert A.W. Lowndes, Donald A. Wollheim. Photo Credit: Jack Robins (1939)

Michel didn’t actually orate his speech, it was given by Donald A. Wollheim due to Michel’s poor health, but let’s see what Michel wrote:

…

What are you people looking for, anyway? Do you really intend to go on harping for more and better science fiction? Do you really think that merely asking for more and better science fiction is, in some miraculous way, to lift the field out of the slough? What makes you think that the editors and publishers of the magazines are going to give you their ears? Have they in the past? No. Can it actually be your intended purpose to continue arguing on the pros and cons of the literature of science fiction forever?

…

Because, gentlemen, there is something in each and every one of you fans which places him automatically above the level of the average person; which, in short, gives him a vastly broadened view of things in general. The outlook is there, the brains are there. Yet, nothing has happened!

…

Science fiction has to do something about it because its very life is bound up with the future and today practical events are working to shape the outline of that future in bold, sharp relief.

Today we are face to face, FACE TO FACE, I repeat, with the choice: CIVILIZATION or BARBARISM -- reason or ignorance.

As idealists, as visionaries, we cannot retreat before this challenge. We must accept it and carry the battle into the enemy's camp. Hitherto, this challenge has not even been recognized, much less accepted.

So come out of your secure cubbyholes of clubrooms and laboratories and meeting places and look at the world before you.

It is swiftly sinking in darkness and chaos. Why? Because the masses are being led by stupid men to a dreary doom.

…

On one hand we are faced with the sickening spectacle of scientists throughout the world turning their backs on cold logic for the magic tinsel of colored military trappings, of a Pirandello in art and a Marconi in radio stooging for the Fascist dictator and general dirty rat, Benito Mussolini. On our own side of the Atlantic, renowned scientists and savants such as Millikan and others bow hypocritically before a standardized version of a God (of which none of them could possibly conceive) and attend rallies and demonstrations to uphold our military pride and honor.

…

Great guns! We have brains, technical brains, introspective brains, thoughts and ideals that would put the greatest minds to shame for scope and insight. Put these brains to work before it is too late! The planet is ready for work, for practical work to wipe clean the slate and start anew. We must start anew if we have to smash every old superstition and outworn idea to do it.

We fans can do a lot towards the realization of this rational idea. We can do that because determination very often means achievement. And how sick we are at base of this dull, unsatisfying world, this stupid asininely organized system of ours which demands that a man brutalize and cynicize himself for the possession of a few dollars in a savage, barbarous, and utterly boring struggle to exist.

We say: "Put a stop to this -- NOW!"

…

The thought of Michel penning at the tender age of twenty these lines so critical of scientists with actual achievements is simply astonishing. Millikan and Marconi had both already won a Nobel prizes! But this is illustrative of the immense self-regard of the fanatics, and of what they wanted to do.

As we get into why science fiction was split off from the rest of wonder stories, you can start to see why it has been so hard to define science fiction as a genre. The people who originated it wanted to use science fiction as a tool to reshape the imaginations of the public. This does not a genre make, according to Cowan’s definition. However, this is a method that I agree with. Art is supposed to form your imagination, to guide and shape your emotions. For example, C. S. Lewis said in The Abolition of Man:

Until quite modern times all teachers and even all men believed the universe to be such that certain emotional reactions on our part could be either congruous or incongruous to it—believed, in fact, that objects did not merely receive, but could merit, our approval or disapproval, our reverence or our contempt.

Art, especially popular and low art, is how emotional reactions are taught. Not always in a deliberate or didactic way, but often simply by harnessing our emotions to entertain us and by expressing shared culture.

But the originators of science fiction and I have very different ends to which we wish to form men. They were committed materialists, hostile at worst or indifferent at best to religion, and from a political spectrum of socialists that believed in the scientific perfectibility of mankind. The Mutation or Death speech is the juvenile expression of this position. I mean that literally, as Sam Moskowitz’s The Immortal Storm makes it clear that the originators of science fiction as a pseudo-genre were in fact teenagers when they did it. The mature expression of these ideas is found in H. G. Wells’ The Open Conspiracy, and gives you a more developed idea of what the original science fiction fanatics were aiming for.

Cowan summarizes Well’s influence:

Mr. Lundwall goes on to mention that the “Vernian monopoly” used to be the dominant form before it was forcibly ejected by editors such as Donald A. Wollheim and those in Fandom. Now Wells’ influence ruled the roost and would define the “genre” going forward. There is a bigger point here. The "Wells' influence" is not the same for readers as it is for Fandom. This influence Mr. Lundwall speaks of is that of political and social engineer, not as a teller of weird tales. The latter is why he was popular and remained so over time. Simply look at any portrayal of him or his works in the mainstream over the decades. There is a reason no one remembers the man's nonfiction, and you will understand why in a future section. But the messaging is what Fandom took from him, and it is what led this group down the dark and dingy path to where it is today. This agenda was pushed by a small crowd who slipped in the door of the industry and decided what the audience should and should not get to read. This was not a natural evolution, and it is not even treated as such. Nonetheless you are expected to accept it unquestioningly.

However, I think my objection to what they were doing is best summed up C. S. Lewis again:

…the difference between the old and the new education will be an important one. Where the old initiated, the new merely ‘conditions’. The old dealt with its pupils as grown birds deal with young birds when they teach them to fly; the new deals with them more as a poultry-keeper deals with young birds—making them this or thus for purposes of which the birds know nothing. In a word, the old was a kind of propagation—men transmitting manhood to men; the new is merely propaganda.

The things we call fantasy and horror were excluded by the science fiction fanatics as too reactionary for their project. Fantasy usually has supernatural elements, and horror relies on traditional morality. Neither of these things fit within the fanatics’ materialistic and scientific vision of the future, and so they had to be cast out.

The most common mechanism for doing this was to claim that works that had these elements were shallow and trite. Let’s go back to Cowan’s summary of Lundwall to see this in action:

But here is where we get the writer's real opinion of adventure. His description of The Castle of Otranto, the single most important and popular Gothic novel, is more or less described as having surface level spooks with nothing under the hood. He describes it as the equivalent to the Penny Dreadfuls and the pulp magazines to come: all surface level, but no deeper content.

What he means is that the horrors are spiritual, implied, and obvious to those reading, and not explicit or bloody. That the characters were not psychologically damaged means they were not deep to him. But what he completely missed was that the horror is an underpinning of a deeper and richer world than the ones the good people are struggling to live through on the page. In other words, he reads Gothic romance for the debauchery and not the spiritual danger under the surface that makes the style work so well. He could not grasp the mindset of the audience it was written for.

Lundwall was not one of the original fanatics, he was simply repeating what they had said, But you can see a similar attitude from Isaac Asimov, another one of the Futurians, when he said that women only existed in the pulps to scream and be rescued.

Rescued from whom, Asimov?

Like Cowan’s assessment of Lundwall’s snark, I think the problem with Asimov was him and not his literary predecessors. You could go read the unbridled femininity of C. L. Moore, a hugely popular pulp author, or the first wave feminism of something like The Well at World’s End, and then compare that with the fact that Asimov was a pervert and a sex pest who couldn’t keep his hands off women he’d barely met.

The pulps weren’t rotten; their critics were stunted and warped by their philosophy and their sins. What is really remarkable is that this calumny was so successful. Anything that was deemed “unscientific” was labeled “fantasy”, an incredibly broad term in practice. Things that were clearly futuristic, and enjoyed by readers who liked science fiction, were labeled “science fantasy”.

Here is Lundwall’s definition of the difference between science fiction and fantasy from the book Science Fiction: What It’s All About, as excerpted by Cowan:

…let us look at the “split” in the genre through Lundwall’s eyes. On one side is “sf” which “deals with man and his relation to scientific and sociological innovations, probable physical occurrences like catastrophes,” in other words, materialism. This is a genre because it focuses on one aspect of the universe: the surface level. The other side is described as “where the scientific side is removed and the logic is constructed to suit the idea,” such as J. R. R. Tolkien’s work. The difference is the latter doesn’t involve “the physical reality as we see it.”

It is true that the Futurians were thorough-going materialists, and that they looked down on anyone who wasn’t. Lundwall’s definition of science fiction is so restrictive it can’t even accommodate space opera:

“With the risk of evoking the wrath of every science fiction old-timer, I am including the Space Opera branch of science fiction in this chapter [on “Fantasy”], as being the direct descendant of the fantasy tale. It is really the same branch, only with some of the old symbols exchanged for new.”

This kind of endless creation of sub-genres to preserve the purity of the ur-genre crept into fantasy too, with the distinction between “High” and “Low” fantasy. Cowan notes:

Unfortunately, the “fantasy” fad left us with a "genre" that is basically Tolkien pastiche built on hard materialism (disguised as "High" Fantasy, the "Low" designation is naturally the inferior one) and nothing else.

This is of course funny because the fantasy designation had been created in the 1930s to wall off things that were insufficiently scientific from the secular scripture of science fiction. I suspect part of the reason why this process kept going on is that readers who liked science fiction often also liked fantasy and horror and weird tales.

Readers, and authors too for that matter, just wouldn’t respect the fanatics made up genre boundaries. I think this is more evidence of Cowan’s fundamental correctness that wonder stories are the real genre, because that is what the audience gravitates to.

Here is an example I came across while writing this review, from the blog Investigations and Fantasies:

Alternatively, we might describe these elements not as a return of the occult to fantasy, but rather as a reflection of the weakening of genre boundaries themselves, with fantasy (already having spawned an “urban fantasy” sub-genre in the 1980s) combining with, for instance, elements typical of the horror and thriller genres.

The occult in fantasy often signals a rejection of (or boredom with) the conventions of Tolkieniesque epic fantasy.

The last sentence in particular stood out to me, as what is the occult in a fantasy book if not a way of rejecting materialism? Materialism was part of the original fanatic definition of science fiction, and then forty years later it crept into fantasy itself as the defining element of “High” fantasy in a kind of mimetic contagion. A high fantasy defined in these terms is anything but Tolkienesque, but for the derivative works of fantasy that became common in the 1980s, authors and editors looked at the massive success of the Lord of the Rings and decided to make books real long, do a detailed backstory, and write trilogies.

But I do think something is missing when we try to understand the contempt with which the Futurians regarded wonder stories that weren’t sufficiently “scientific” in their eyes. I think the key item missing from Cowan’s narrative is: who did the Futurians see as their real competitors in re-shaping the future?

When it comes down to it, Lundwall doesn’t actually care about “scientific and sociological innovations, probable physical occurrences like catastrophes”, which space opera has in spades. Something else is the real problem. You can get a hint of what it is from Goulart’s book, which is in general pretty positive about the pulps, except for one thing: the weird tale. Cowan summarizes Goulart’s views:

The centerpiece of this era was undoubtedly Weird Tales, which started in 1923 and wrapped up in 1954, spanning both the peak of pulp as well as its downfall. Few magazines encompass the pulp era better than it did.

"A rallying point for every sort of monster, ghost and fiend, Weird Tales was edited in the '20's and '30's by Farnsworth Wright . . . The pulp, in its nearly (I believe he means "over") thirty years years, offered readers a smorgasbord of horrors . . ."

It was at this point reading that it became clear to me that Mr. Goulart was not much of a fan of these sorts of stories. That is fine, we all have our tastes, and I do enjoy that unlike Mr. Lundwall, that he even mentioned them at all, but he does not spend much of any time on these stories nor does he mention their clear Gothic influence, which is a bit more than the hokey horror cliché that era is painted as being.

There is another thread of influence in both the pulps and science fiction: the occult. My own theory, which developed as I was reading The Last Fanatics, is that the contempt with which the fanatics held the spiritual world was a reaction to their main competitors. If you want to look for another individual with similar connections in genre literature as the original fanatics, I might suggest Jack Parsons. Parsons was both a founder of rocketry and a black magician:

Jack Parsons seems to have known, and sometimes rented rooms to, most of the great names of the Golden Age of science fiction. His circle included Ray Bradbury, Robert Heinlein, L. Sprague de Camp, and many others. L. Ron Hubbard was of their number: Parsons not only performed apocalyptic ritual magic with him, but was fleeced out of more than $20,000 by him. Moreover, Parsons moved at the fringes of the Communist underground of scientists and technicians; he attended Leftist salons with Robert Oppenheimer's brother, a known Party member, which was among the reasons for Parsons' many awkward interviews with the FBI in later years. In retrospect, however, we see that politics was the least of his subversions; he was actually trying to inaugurate a new age through magic. Most dreadful of all, there was this: Jack Parsons wrote macabre poetry that makes Lovecraft's look good.

There is a strange lacuna in Lundwall’s account around “Weird Tales”. Almost like he didn’t mention it on purpose. “Weird Tales” was the home of the kind of theosophically-influenced genre fiction that was quite popular for a long time. But Lundwall does take time to denounce Richard Shaver and the Shaver Mysteries that ran in “Amazing Stories”. Perhaps the amount of vitriol heaped on Shaver and Raymond Palmer by the fanatics for publishing Shaver was that the opposing camp had published heresy in the magazine that had started the materialist fanatic movement in the first place.

A. E. Van Vogt is also an interesting case. Van Vogt was one of the authors promoted by John W. Campbell during his editorship of “Amazing Stories”, but later generations of science fiction fans, especially Damon Knight, tore Van Vogt down. But Van Vogt was associated with the theosophical, mystical side of genre literature, so perhaps this was another instance of the occult/materialist conflict among genre authors. Even Campbell himself seems to have been involved in both sides of this. However, I have not done the kind of research that Cowan did in order to substantiate this, so I’ll leave it be.

Cowan has done an excellent job of providing written evidence that the fanatics intentionally split wonder stories into science fiction and a fantasy rump, on the basis of what they found best for their purposes. Cowan has also provided us with vast detail on what the fanatics wanted. I only included select bits in this very long book review, there is much, much more in the book. Their intent was to create a better future by creating better men through fiction. In order to do that, they needed to eliminate mimetic competition, but what they actually ended up doing was driving their audience away.

Here is Cowan’s summary of what happened:

You see, industrialization and World War I changed human nature forever and now our standards and imaginations must change to match Neo Reality. We live in a material world now, so pretending we do not is harmful and must be fought against with all manner of deceitful tactics. Don't live in the past! Kill it if you have to. This is essentially Fandom's entire thesis statement as to why they created an anti-human space that would consume Wonder and Imagination throughout the 20th century.

You should go read The Last Fanatics for yourself [Amazon link]. Reading it changed how I see the kind of fiction I like to read, and even helped open up new vistas of things I might like to read. I do think there is more to be said on the evolution of genre fiction and the background influences of its authors.

In particular, I’d like to learn more about the later life of Donald A. Wollheim. Wollheim is something of a villain in Cowan’s telling, but most of the material here focuses on things he did as a teenager. Later in life, Wollheim was a prominent author and editor and publisher [DAW Books}. Wollheim published a number of authors who didn’t fit the Futurian mold, so it is clear that his life cannot be solely judged on the things he said and did when so young.

I’d also like to find out more about the theosophical/occult strand of influence in genre fiction. I can see it pretty clearly, but I don’t yet know where to get the kind of first-person accounts that made The Last Fanatics so compelling an argument. Cowan’s not at fault for not indulging my interests here, I’m simply identifying where I can see that his thesis can be expanded.

Don’t let those things keep you from reading this book, and from engaging with the key insight that science fiction doesn’t exist.

I was provided a review copy by the author.

My other book reviews | Reading Log

Other works by JD Cowan

Gemini Man series

Gemini Warrior: Gemini Man Book 1

Comments ()