2022 Book Market

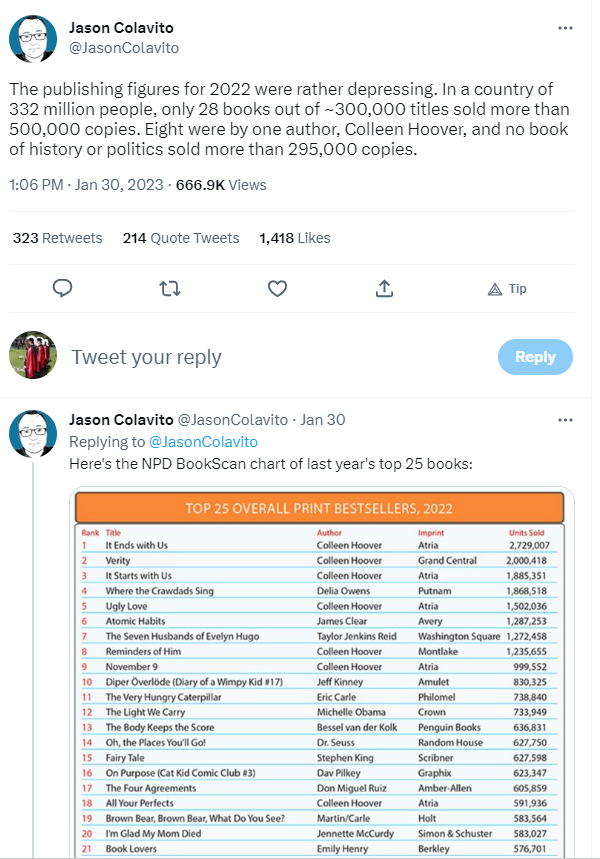

I stumbled on some great data on the book market for 2022 on Twitter, so I’m copying it here as it is so important to build up your quantitative sense with reference to handy facts. It is also good to have a reality check on how bestsellers can make huge sales and then vanish without a trace. I read a lot, but I had no idea at all who Colleen Hoover was, or how many books she sold. I’m glad to see a fellow Gen Y making it big. However, I’m guessing it won’t be too long before Hoover is as forgotten as Florence L. Barclay.

I also like to link things together, because this is an important skill in building up a coherent picture of the world. For example, these NPD Bookscan numbers are print only, and retail only. These numbers don’t include the physical books or the ebooks of the world’s biggest book seller, Amazon.

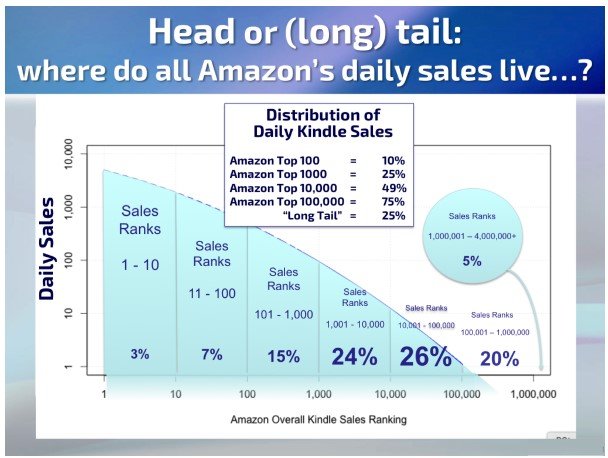

In my September 2022 post The State of the Book Market, I had some numbers on ebook sales from 2016. Just the top ten on Amazon come to 3,000 a day or so, which would be another million books a year just for the top ten. If the 3% daily volume number is right, then Amazon was doing 30ish million ebooks a year. Presumably that number has grown.

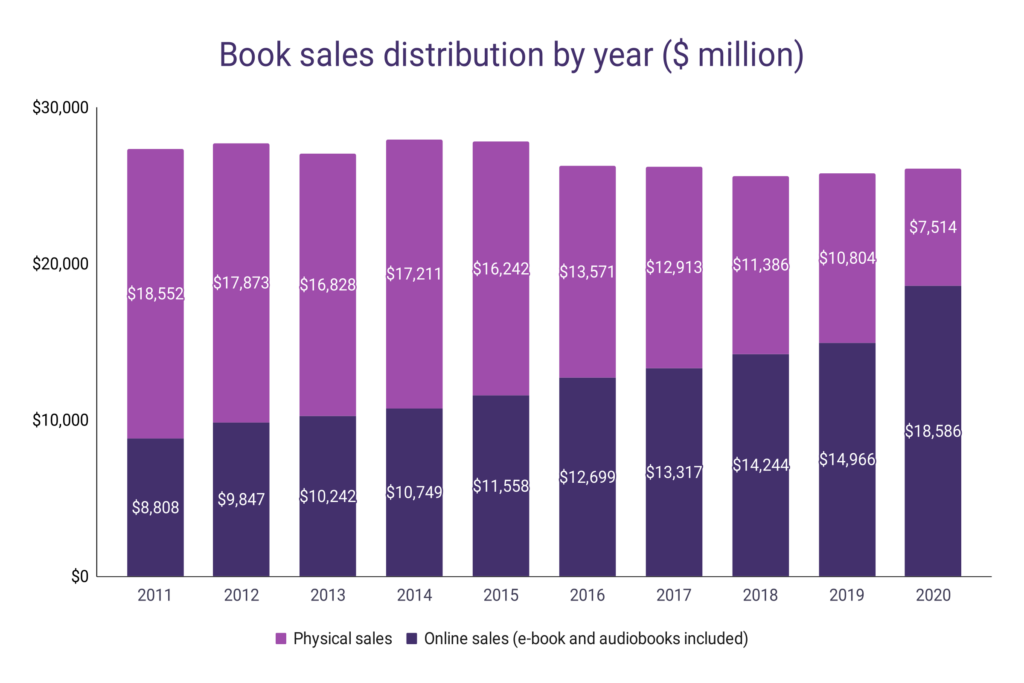

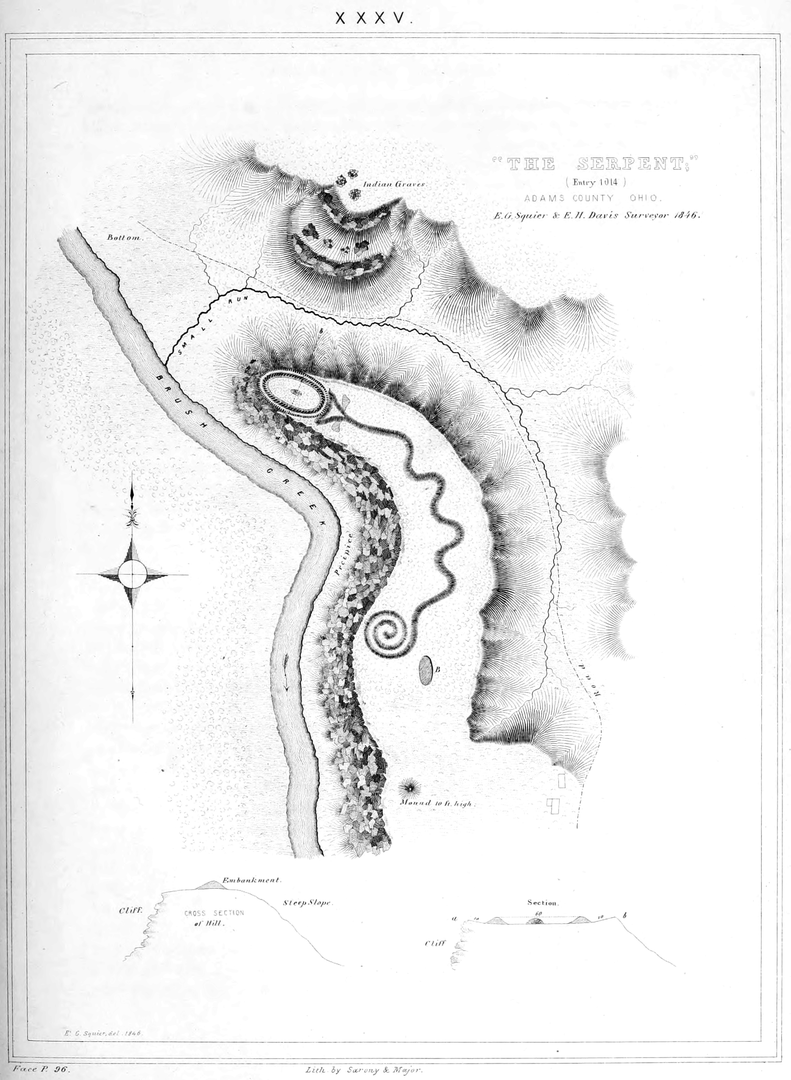

That same Twitter thread links to WordsRated.com, which offers this chart of book sales channels:

At this point, NPD Bookscan numbers will be going down simply because the point of sale barcode scanning that is the heart of their data is a shrinking share of how people get books. To a first approximation, you could probably double any number from NPD Bookscan as an overall market estimate.

Unfortunately, the methodology of WordsRated is far less transparent than the now defunct AuthorEarnings I used for the Amazon data, so keep that in mind as you weigh the importance of this data.

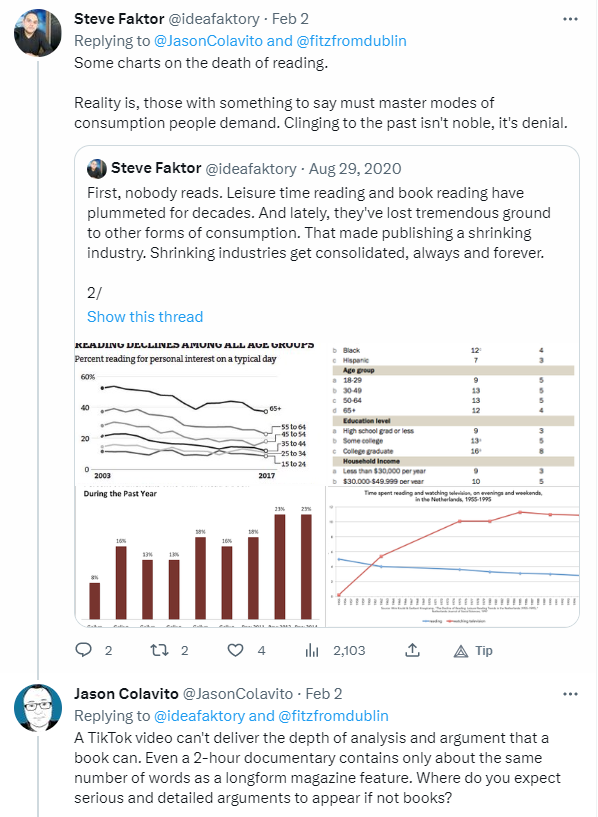

Further on down the Twitter thread, we get to an argument I find more compelling: reading in general and books in particular are a higher-bandwidth way of transmitting information.

Much like with the decline of the pulps, a big part of the decline of reading is substitution. People watch TV or play videogames. They might also scroll Twitter. In some cases, this represents a real shift in intellectual engagement. In other cases, I’m not so sure.

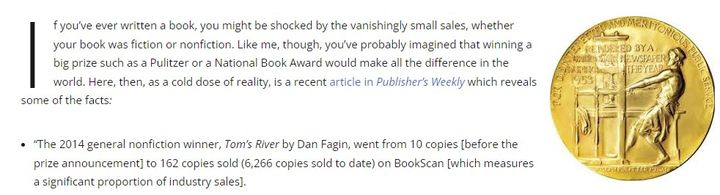

Jason Colavito laments in the top post that no book on history or politics sold more than 295,000 copies [590,000? using the market correction for print?], but in my experience almost all serious political commentary moved first to blogs, then to Twitter, and now maybe to Substack.

I think Twitter can be great for politics and history. And I keep finding new Substacks that make serious, book-length arguments on a variety of in-depth topics. So while I read a lot more than average, my non-fiction book reading is only a handful in a year, because I get all that information in another way.

However, I do read it. Podcasts are super popular, but frustratingly low bandwidth for me. In my professional life, webinars are the hot thing, but they just take too long for me! For people who can’t read ten times faster than they listen, that might not be the case. I do love YouTube for repair videos though, even as an engineer, manuals suck for explaining things like that.

So while I love complaining about the decline of reading too, I’m not actually worried.

Comments ()