Book Reviews and the Great Conversation: What Readers Like Versus What Authors Like

Dune is very different than its sequels

I am indebted to The Pulp Archivist for the title of this post, but I see it as an extension of my blog from 2020 What authors like versus what readers like.

As someone who really likes adventure books, and really likes to blog about adventure books, there is a fascinating tension in the whole field because it is fundamentally popular entertainment, but the people who like to create these stories and the people like me who like to talk about them often find these stories interesting for reasons at cross purposes with their being popular entertainment.

There is a commercial or business aspect here that a vocal portion of the readers, people like me, are not necessarily representative of the bigger pool of readers and buyers. As low art, adventure stories are about selling escapism and joy to the reading or watching public. Other genres are too, they just are selling different emotional experiences. However, there is a part of the market that wants more than that.

“Abs genre” for the win

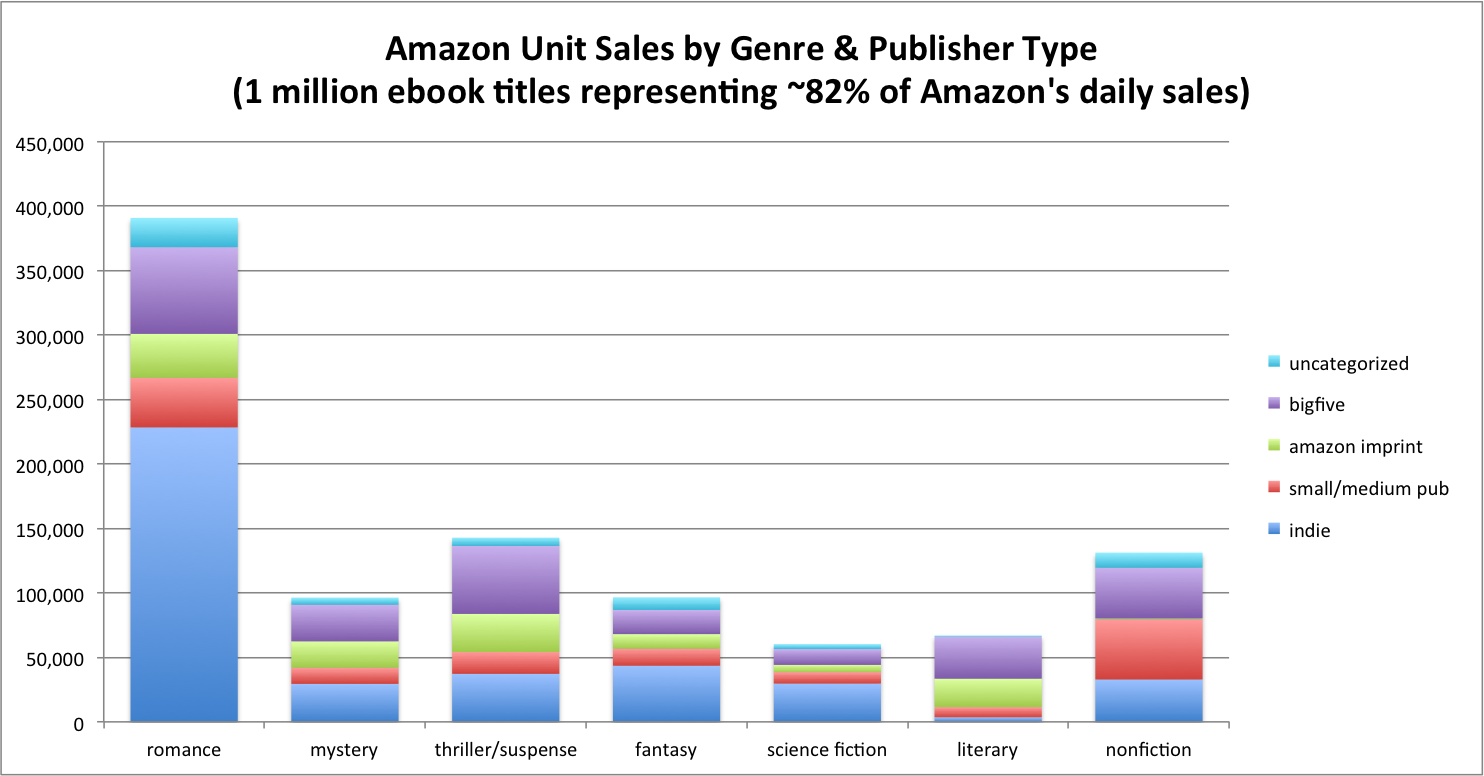

Among authors, there are different approaches to this. Some authors happily write exactly what the audience wants and nothing more. Think of the “abs genre” books that currently dominate ebook sales. Like the bulk of playwrights throughout history, these authors will pass from our collective memory unremarked. However, there are authors who are interested in ideas, in the Great Conversation that is part of the Western intellectual tradition.

But even among those who want something more than just entertainment, some pretty significant differences emerge. For example, one way of looking at it is whether an author is focused on story or entertainment first, or on message first. I find “message first” fiction rather grating much of the time, but this may partly be an artifact that the vast majority of message fiction right now is spreading a message I find abhorrent. So an interesting data point to consider is a "message first” author of futuristic and mythic fiction that I largely agree with: C. S. Lewis.

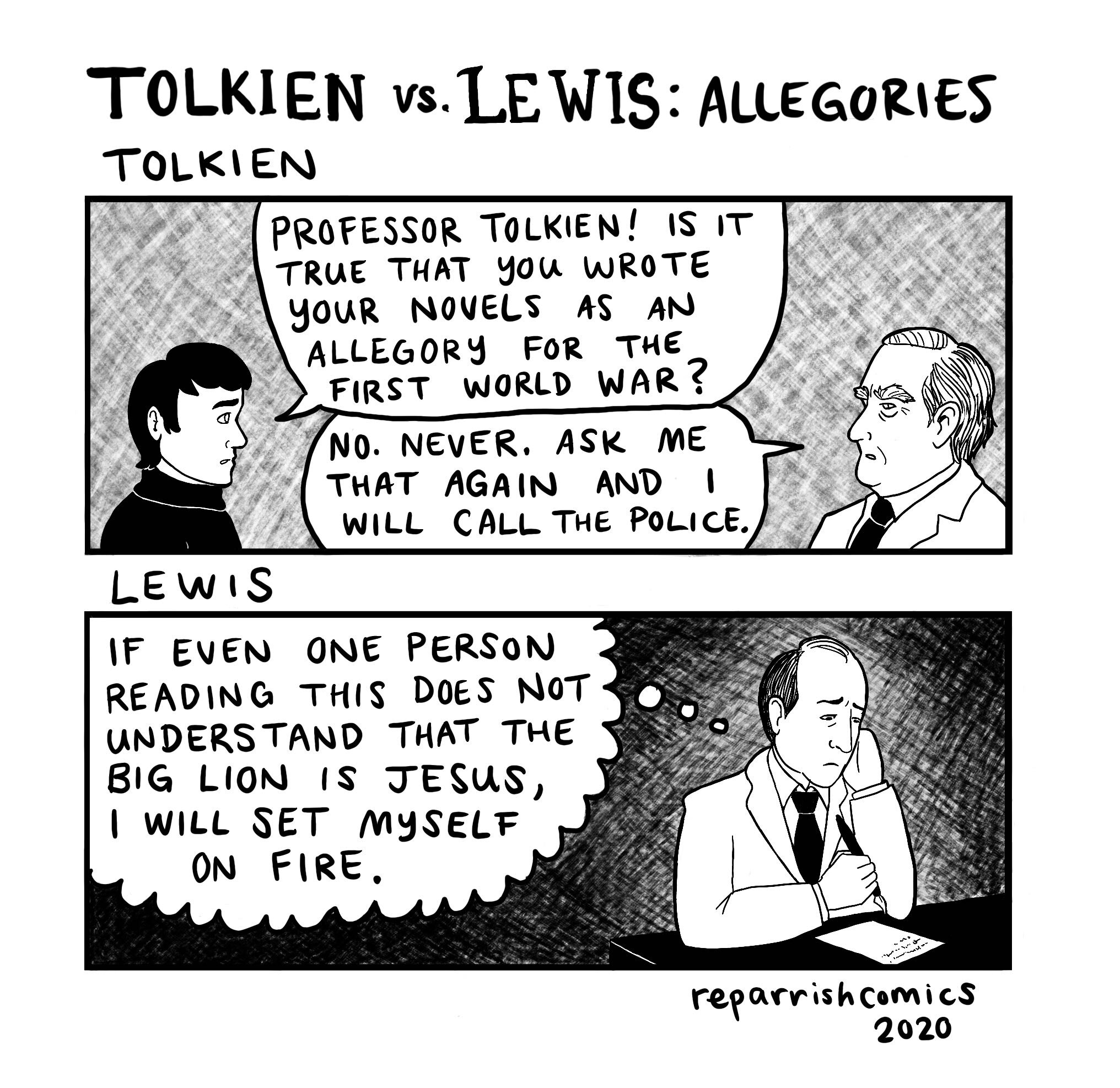

Absolutely no one has ever doubted that Lewis was trying to use The Chronicles of Narnia as a tool of Christian evangelization. Since I am in favor of that, it bothers me less, but I still find that I prefer authors who take a more subtle approach. C. S. Lewis and J. R. R. Tolkien famously didn’t agree on this subject, although it is usually limited to the topic of whether The Lord of the Rings is an allegory.

Tolkien strenuously insisted that LoTR is not an allegory, which is true in a technical sense. However, people often use that word in an expanded sense to mean writing a story that engages in the Great Conversation in some way, so this assertion is often confusing. Once you know what to look for, the Christian symbolism of Tolkien’s work is overwhelming, but many people miss it nonetheless. It has been cruelly but not unfairly noted that the Good Professor may have led more people to Wicca than Catholicism with his magnum opus.

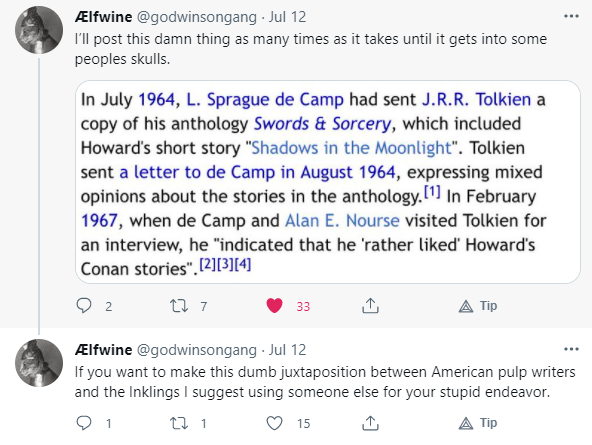

I find it more understandable to see this dispute between Lewis and Tolkien as part of a bigger dispute in the twentieth century over whether entertainment or message came first. Ultimately, I would probably place both of them as mostly on the side of story versus message. Tolkien said some nice things about Robert E. Howard, while Lewis said that he wanted a more speculative element in science fiction but was bored by Campbelline Big Men with Screwdrivers.

Pulp era science fiction was very much in the entertainment first mode, which much vexed the Futurians. John Campbell’s signature style certainly moved science fiction towards the message, but I think much of the enduring appeal of the Campbelline-era is that adventure and entertainment can hybridize well with the kind of social science fiction that Campbell pushed as editor of Astounding.

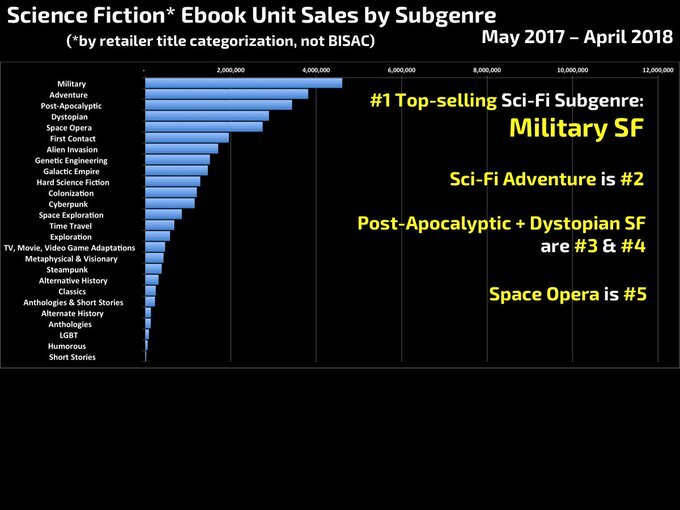

However, in retrospect, it also seems pretty clear that an exaggerated focus on message kills your audience. Campbell’s editorship of Astounding coincided with a large decline in circulation. His successors in science fiction moved further away from adventure, with message coming to dominate the field. Today, Amazon numbers make it clear that contemporary science fiction and fantasy [which don’t exist!] are worst selling genre of fiction.

However within science fiction, it is pretty clear that the best selling works tend more toward adventure. Fantasy may be a different story, with grimdark doorstoppers the name of the game. On the other hand, every time Will Wight releases a book in his popular Cradle chinoserie series, he hits #1 on the Amazon ebook sales.

To return to the core theme here: Campbell and the Futurians and Damon Knight and others like them made it clear that they wanted to participate in the Great Conversation. They felt like science fiction was a way to express ideas and explore new worlds, and maybe most importantly become influential among the right people. Having read some pulp era science fiction, I don’t think the Futurians’ criticisms were entirely valid, but there was also a lot of real talent in their group that ensures their memory and their ideas will endure.

Unfortunately, I think that the kind of book reviews that I like to do, or that my late friend John J. Reilly used to do contribute to the problem. Let me give you a recent example. Jason Anspach and Nick Cole are currently some of the most popular authors in futuristic adventure fiction, with Galaxy’s Edge and Forgotten Ruin. For the most part, Anspach and Cole write military sci-fi, which has largely supplanted space opera. However, they occasionally do something a little crazy.

The recent Gods & Legionnaires makes for a fascinating case study. As elements of the book borrow heavily from A. E. Van Vogt’s “Centaurus II”, I think this makes it all the more appropriate. Van Vogt was a popular Campbelline era author, although his star was later eclipsed by Damon Knight, who found him unworthy, or more likely just guilty of professing the wrong ideas. Van Vogt was one of the authors who simultaneously made science fiction more serious and less popular, and Gods & Legionnaires is a imitation of that.

The “Gods” section of the book is allusive, multilayered, and difficult to interpret. It was masterfully done. It was also extremely unpopular with the fans of Galaxy’s Edge, who were mostly baffled by it, but a significant minority actively hated it. I of course loved it, and said so. Anspach and Cole don’t really seem like they are motivated by critical opinion, and for the most part they stick to what the fans like.

But I bet it was fun to write that book. I can see how if you wanted a certain kind of attention, you would write a whole lot more books like that. Pleasing me, as a book reviewer with an eye towards allusion and history, probably isn’t a route to commercial success. I think the most skilled authors can do so, but there are authors who sell a lot of books who write things that don’t provide grist for the review mill.

I’ve read books that are perfectly enjoyable, but don’t leave me with much to say. Thus, the books I review will always be slanted towards the thought-provoking, rather than the simply entertaining. And if no one talks about your books, you can’t really participate in the Great Conversation, because there is no conversation.

At the end, I don’t think this tension can be or should be resolved. It is at root a creative tension, with the need to entertain pulling away from the desire to be interesting or thoughtful or explorative. Sometimes, a particular story succeeds at combining entertainment and speculation by luck rather than skill. I think you can find lots of examples of this, with Dune being a particularly striking one. Thus, when the author follows up and fleshes out their ideas, the entertainment tends to fall away. The books might still be interesting, to a reader like me, but in such cases the sequels will be less popular.

Right now, I advocate for more adventure and more escapism, because that is what I think readers want and are not getting. But I would be sad if all the interesting books went away.

Comments ()