The Long View: The Life of Thomas More

Two Thomases

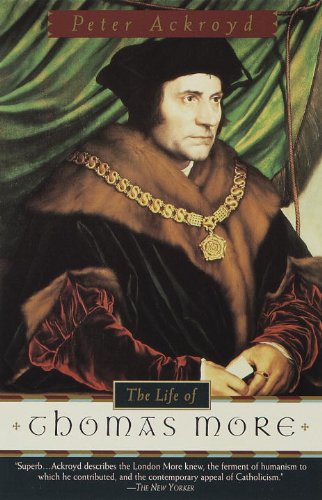

The two oak panel portraits by Hans Holbein the Younger above are a fascinating study in contrasts. Holbein painted the two men only six years apart or so. Each man sat for a portrait at the peak of his power, More in 1527, Cromwell between 1532 and 1534. Yet the two men couldn't be more different in these paintings. More leaps off the panel, full of intensity and life, yet also humanity. Cromwell, on the other hand, seems to blend into the background, and all the details are more muted.

In life, the two men could not have been more different as well. Both eventually were executed by Henry VIII for crimes against the state, but only More could plausibly have been said to have died for principle rather than simply falling victim of his enemies at court.

The hardest part about understanding Thomas More is that he inspires either love or hate that is disconnected from the reality of his life. As a canonized saint in the Catholic Church, More is guaranteed defenders. On the other hand, in the English-speaking world, it is easy to find equally negative portrayals from Protestants who remember that More was involved in the interrogation and execution of dissenters before Henry broke with Rome.

On the gripping hand, More truly was a remarkable man; funny and educated, notably honest and fair in an era not known for either trait. He was also ambitious, and heavily involved in the politics of the day, which often meant using disgraced former colleagues as stepping stones. Cardinal Wolsey comes to mind.

Unfortunately for More, and for everyone who lived through it, the Renaissance started on an enthusiastic reformist note, and ended in bloodshed and tears.

The Life of Thomas More

by Peter Ackroyd

Doubleday, 1998

447 Pages, US $30.00

ISBN: 0-385-47709-0

Nothing so concentrates the mind of biographers as the execution of their subject for political crimes. Even more than assassination, such a death gives a life a rare degree of dramatic coherence. There have been few people in history of which this is more true than Thomas More, who was beheaded in 1535 for refusing to swear an oath accepting Henry VIII as head of the Church in England. Born in 1478, just at the end of the English Middle Ages, More was one of the choice spirits who helped bring Renaissance Humanism to his country. The close friend of Erasmus and the author of the enigmatic "Utopia," he is sometimes presented as the token of a better Reformation that did not happen. He was "the best lawyer in Europe," by some accounts: his reputation for honesty and impartiality as a municipal magistrate was still a feature of popular culture in London fifty years after his execution. He worked on the international level as a successful commercial negotiator for the English guilds and as a diplomat for the young King Henry. Everything in his life followed a logical if not inevitable progression to his term as Chancellor from 1529 to 1532, and then to his death so soon thereafter. Far more than his mercurial contemporary, Martin Luther, More could "do no other."

Thomas More was also very smart and very funny, unlike some of the people who interpret his life and works. On one hand, Sir Thomas More is also Saint Thomas More, canonized on the 400th anniversary of his death, and much of the writing about him has always been literally hagiographical. On the other hand, More has attracted his share of debunking, both from historians with a psychological bent and from Protestant polemicists. More figures in a sinister fashion in Foxe's "Book of Martyrs," and any appreciation of him has to take into account that he was involved in the execution of Protestants while Chancellor.

This perceptive and well-informed biography by Peter Ackroyd must rank among the best. The author of "Hawksmoor" and "First Light," Ackroyd is that rarity, a tough-minded spiritual writer. He knows the period and the personalities. He quotes liberally in the pithy English (and Latin) of the period, so that, as much as possible, these very articulate people seem to speak for themselves. Most important, though Ackroyd tries to address all the major questions that have been raised in the literature, he does not claim to have "solved" Thomas More. Ackroyd returns again and again to that famous Hans Holbein portrait of More as Lord Chancellor, beautifully reproduced in the book with a small selection of other fine illustrations. The personality it displays is composed, acute, and as enigmatic in its own way as the Mona Lisa. What is hidden is as important as what is revealed: underneath the ermine and velvet, we are reminded, More is wearing a hair shirt.

More's complexity is apparent from his most famous work, "Utopia," first published in 1516. All that most of us remember about the book is that the title is Greek for "nowhere" and that it is a description of an ideal society. The name does indeed mean "nowhere" (More had originally planned to call the book "Nusquama"), but the rest of that characterization is wildly misleading. To a large extent, the work is actually a satire on Plato's "Republic." The island of Utopia has more in common with Jonathan Swift's flying island of Laputa in "Gulliver's Travels" than with the behaviorist paradise in B.F. Skinner's "Walden II." There is more to it than satire, of course. Ackroyd follows other perceptive 20th-century critics in highlighting the fact that the book is, among other things, an exploration of the limits of philosophy in ethics and social theory.

The society described in "Utopia" is a land of the "pagan virtues." Catholic natural law theory holds that human beings, unaided by revelation, can still discover quite a lot of the moral universe, but very far from everything. Thus, for instance, a virtuous pagan polity might have an honest, largely democratic government, but still not know enough to forbid infanticide and euthanasia. This was the paradox that Christian Humanists of More's generation wrestled with every day: there was so much in the Classical tradition that was obviously good and true, and yet even the wisest of the ancient philosophers advocated doctrines that they found morally and theologically repugnant. More's "Utopia" does not presume to resolve the paradox. Rather, when More wrote "Utopia," he was a reform-minded young man, in a generation of reform-minded young men, who was cautioning that even the best society devised by unaided reason would still not be good enough.

Nevertheless, as a politically active, well-connected young lawyer, More believed that a little application of reason would do both his country and the Church a world of good. More was raised in the reign of Henry VII, the grasping, efficient monarch who ended the long period of civil strife known as the Wars of the Roses. Along with peace, Henry brought the first whiff of autocratic government as he struggled to expand the powers of the monarchy against the local civic corporations. (His use of the Archbishop of Canterbury as his Chancellor, not in itself an innovation, was not seen at the time as the beginning of a wider co-optation of the Church.) Though London had come through the civil wars with little damage, the countryside was in distress because of the increasing tendency of the wealthy to enclose and claim land for their own use, in effect displacing peasants with sheep. As for the Church, from 1503 to 1513 the successor of St. Peter was Julian II, the warrior-pope whom Erasmus called, with some reason, "Il Terribile." At ground level, the Church was almost universally acknowledged to be corrupt. Many local clergy regarded their parish appointments as no-show jobs, while the people were drawn to superstitious novelties that had little to do with Catholic theology but that did enrich their proponents.

More and the other London Humanists looked to the accession of 18-year-old Henry VIII in 1509 as an occasion to start to put things right. The Renaissance just before the Reformation was an extraordinarily hopeful time. (This was most true in the north of Europe. In Spain, the spirit of the Reconquista was already limiting the sense of possibility, while central Europe was in danger of being overrun by the Ottoman Empire.) If educated people did not have faith in progress like that of the 19th century, still they no longer had a sense of the Classical past as either overwhelmingly superior or incomprehensibly strange. Like the medievals, they continued to consider the appearance of Christianity as the decisive event in history, but they also realized that there were things that their own culture could and should learn from antiquity. Additionally, they realized that there were ways that antiquity could be improved upon, even in secular matters. In the years just after 1500, many intelligent and powerful people were of a mind to make proposals for moderate reform, and others were of a mind to listen to them. This was not true 30 years later, and Thomas More's career coincided with the period during which intellectual positions hardened and public life became more brutal.

Ackroyd's biography is not a hagiography; to a large extent, it is a social history. We learn about the life of the professional classes in London (Thomas More's father, John, was a prominent barrister and judge in his own right). We also learn about the various levels of the English judicial system, right up to the Star Chamber, on all of which More served. Much of this system More managed to colonize with his relatives and "affiliations" during his illustrious career. In some ways, the most interesting part of the book is its description of More's large household, with its resident fool and staff of tutors for the children. Tudor England was notable for its learned ladies, but More's eldest daughter, Margaret, may have been the best-educated woman of her day. More's first wife, Jane Colt, had died young, after giving birth to his four children. He soon thereafter married a wealthy widow, Alice Middleton. As the ever-practical Dame Alice, she was the terror of wandering scholars who overstayed their welcome. She also seems to have inspired Thomas More to devise a repertoire of jokes of the "Take my wife -- please!" variety. She gave as good as she got, however, and a high time seems to have been had by all.

You don't get to be Lord Chancellor by accident, and Thomas More, though unusually honest for a Tudor official, was also very ambitious. By his own admission, he told minor lies for effect. (He once said that "Utopia" had been published without his knowledge, though in fact he had been preoccupied with getting it into print for almost a year.) He was also not above denouncing the conveniently dead or disgraced to whom he had once been allied. Whatever faults Henry VII may have had, Thomas More's father had certainly prospered under his patronage, yet the son denounced the old king as a tyrant when Henry VIII came to power. The same pattern applied after the disgrace of Thomas More's one-time colleague and predecessor as Chancellor, Cardinal Wolsey, with the difference that More himself had owed the imperious old prelate many debts of gratitude. After More's own fall from power, he denounced the Maid of Kent, Elizabeth Barton, after her execution. He did this despite the fact he had met with her on several occasions and had, at one time, lent much credence to her prophecies about the doom that would fall on the king because of his divorce of Catherine of Aragon.

Then there is the fact that Moore himself died with blood on his hands. Though he did not, as the "Book of Martyrs" alleges, torture suspected Lutherans personally, nevertheless he did interrogate them, and he approved of burning heretics on principle. One of the striking aspects of the period covered by the book is the way that the treatment of religious nonconformists got harsher and harsher as the 16th century progressed. In the early part of the century, people caught distributing heretical literature were let off with a warning or a fine. Indeed, nothing at all was likely to happen to people who kept their opinions to themselves. More's own son-in-law, William Roper, was one of the early Lutheran party, though More eventually dissuaded him. Still, the maximum penalty was always theoretically available for religious nonconformists, and as time went on it was applied more and more frequently.

Similarly, More's own opinions became less plastic with the passage of time. Once he had favored a vernacular translation of the Bible and criticized the excesses of monasticism. He derided much of the traditional body of scholasticism in favor of the New Learning. He wanted theology to give higher priority to the Fathers of the early Christian centuries, rather than to Aquinas and his successors. Early in his career, apparently, he had believed in only a very moderate version of papal supremacy, with the pope as little more than the president of the college of bishops. Except for his devotion to the Fathers, none of these ideas remained with him by the time he became Chancellor. It was not so much that he had changed his mind. His early ideas about the role of the papacy, for instance, were unconsidered notions that did not survive his sustained study of the question. It was his sense of the times that changed. Believing that he might be living in the days just prior to the appearance of Antichrist, he felt that reforms were a luxury that could not even be discussed.

Though More was involved in prosecutions for heresy, questions of faith were not really central to his job as Lord Chancellor, which was concerned primarily with fiscal questions and the administration of civil justice. (More was, by all accounts, a respected and efficient chief judge.) His major contribution to the religious strife of the first three decades of the century was in the form of polemics. Earlier in his career under Henry VIII, he had exchanged polemics with Martin Luther, who had ventured to criticize the king. As Chancellor, he continued to write polemics. (He has the distinction of have written the longest religious polemic in English, which weighed in at 500,000 words.) These were increasingly desperate in tone, for the excellent reason that he knew that the very opinions he was refuting, the opinions for which he was willing to send men to be burned alive, were becoming fashionable at court.

Why exactly was Thomas More beheaded on Tower Hill in 1535? On a historical level, the problem was that it had suddenly become convenient for King Henry to believe that the pope had no jurisdiction in England. The matter was complicated. The pope had granted a dispensation to Henry to marry his brother's widow, the Spanish princess Catherine of Aragon. (See Leviticus 18:16, 20:21; cf Deuteronomy 25:5) When she failed to produce a male heir, however, and as he became more and more besotted with Anne Boleyn, Henry decided that it would be a good idea if he had never been married to Catherine after all. This required the discovery that the pope had never had the power to grant the dispensation in the first place. The Lutheran books that the king's courtiers had been urging upon him provided theoretical arguments for why the pope had never had the jurisdiction the papacy had so long claimed. The books even argued that the civil leaders of a state should also be the head of its Church.

Henry never became a Lutheran: he was quite capable of executing people who espoused Luther's view of the Eucharist, for instance. Nevertheless, he did adopt Luther's views on the relationship of Church and State. He also caused parliament to require that everyone in England take an oath accepting the validity of his marriage to Anne and accepting his role as the head of the Church in England. Because Thomas More refused to take the oath, he was beheaded for treason. (This was an unusually mild punishment, by the way: priests executed by Henry's government for the same reason were drawn-and-quartered, a procedure that involved disembowlment, among other things.)

On a personal level, Ackroyd argues that More held out to the end because he was the last medieval man. Ackroyd attributes More's decision to More's immersion in the ancient consensus of Catholicism. More's conscience, in this reading, is quite different from Luther's conscience, which was personal, almost Faustian. More's conscience was a "con scientia," a "knowing with" that encompassed the faithful on Earth, the suffering in Purgatory and the Blessed in Heaven. More's refusal to take the oath was therefore an act of submission rather than of self-assertion.

The problem with this contrast of More and Luther is that it gets things backwards. Thomas More was a cosmopolitan, a man who lived at the level of his times. Of the two, the disgruntled theologian Luther, with his private ecstasies and his personal devils, was by far the more medieval figure of the two. In any case, we must remember what an extraordinarily tyrannical development the early Reformation was. It was associated with the enclosure of land and, in Germany, the strengthening of serfdom. It diminished or destroyed the local municipal governments and corporations in favor of centralizing monarchies. It was also oddly frivolous. The last medieval English monarch, Henry VII, had chipped in some of the royal gold to back the exploration of North America by the merchants of Bristol. His reforming son, Henry VIII, frittered away the treasury in senseless European wars. These were the trends and policies that More had always opposed.

It may be possible to explain the negative side of how More could have chosen to suffer the full penalty of the law, despite the many opportunities he was given to join the rest of his countrymen in the new definition of English patriotism. It seems terribly strange, here at the end of the 20th century, that a man whose job it had been to deny freedom of conscience to others had the temerity to demand it for himself. However, I think that way of putting the matter somewhat misstates the way that More saw it. Protestantism of different sorts had its English adherents in More's day, especially in certain guilds and at the universities, but it was not a popular movement. When he sought to stamp out heterodox teaching in England, he was seeking to maintain public order, as it had been defined for a thousand years, from zealots who were trying to disrupt it. That is somewhat different from trying to compel the conscience of individuals, which is what King Henry tried to do when he required all his subjects to swear loyalty to his marriage and his new Church. All More was asking for was to be left alone. This may seem to be a lawyerly distinction, but then Thomas More was the best lawyer in Europe.

As for the positive explanation of why More acted as he did, the matter really is fundamentally mysterious. Sir Thomas More is also Saint Thomas More, who said this to the jury that condemned him:

"More haue I not to say, my Lordes, but that like as the blessed Apostle St Pawle, as we read in thactes of the Apostles, was present, and consented to the death of St Stephen, and kepte their clothes that stoned him to deathe, and yeat be they nowe both twayne holy Sainctes in heaven, and shall continue there frendes for euer, So I verily truste, and shall therefore hartelye pray, that thoughe your Lordshippes haue nowe here in the earthe bine Judges to my comdemnacion, we may yeat hearafter in heaven meerily all meete together, to our euerlasting saluacion and thus I desire Almighty God to preserue and defende the kinges Maiestie, and to send him good counsaile."

Copyright © 1999 by John J. Reilly

The Life of Thomas More By Peter Ackroyd

Comments ()