Federation by H. Beam Piper

Federation is a collection of five of H. Beam Piper's short stories, curated and re-published by John F. Carr in an Ace Paperback edition in 1981. The book leads off with a preface by Jerry Pournelle, who knew Piper through science fiction fandom before Piper's suicide. Carr has an illuminating introduction, giving a short history of Piper's life and work.

When I was in college for physics, my advisor really hated the World's Smartest Garbage Man character in the Dilbert comic strip. He insisted that it wasn't possible to have a job like that and still be intellectually fulfilled. I don't think my advisor was wrong, but it striking that Piper worked for the Pennsylvania Railroad from 1922 through 1956, never got a university education, and yet still managed to acquire a broad and deep education in science and history. That isn't the recommended, or the easy path, but it certainly worked for Piper. Or at least until it didn't.

A fair amount of Piper's writing is contemporaneous with his last decade at the railroad. According to Carr, Piper only left the railroad after the death of his mother, whom he supported in her dotage. Piper mostly seems to have written short fiction while also working for the railroad; Piper's novels, other than Uller Uprising, date from the post-railroad period.

As interesting as these biographical details are, it is of course the stories that matter. And what stories! The five stories that Carr selected for Federation give us a span of seven centuries or so in Piper's Terro-Human future history, and while there is an obvious similarity in their background, Piper is also clearly taking inspiration from cyclical theories of history, giving us a glimpse of the greater setting through indirect exposition.

Piper, like many authors of his generation, revised, reused, and reworked his ideas extensively. In this collection, there are alternate short story versions of two later novels, The Cosmic Computer, and Lord Kalvan of Otherwhen. The other three stories only existed in their shorter forms, although perhaps if he had lived Piper might have attempted to novelize them.

Let's now turn to these stories.

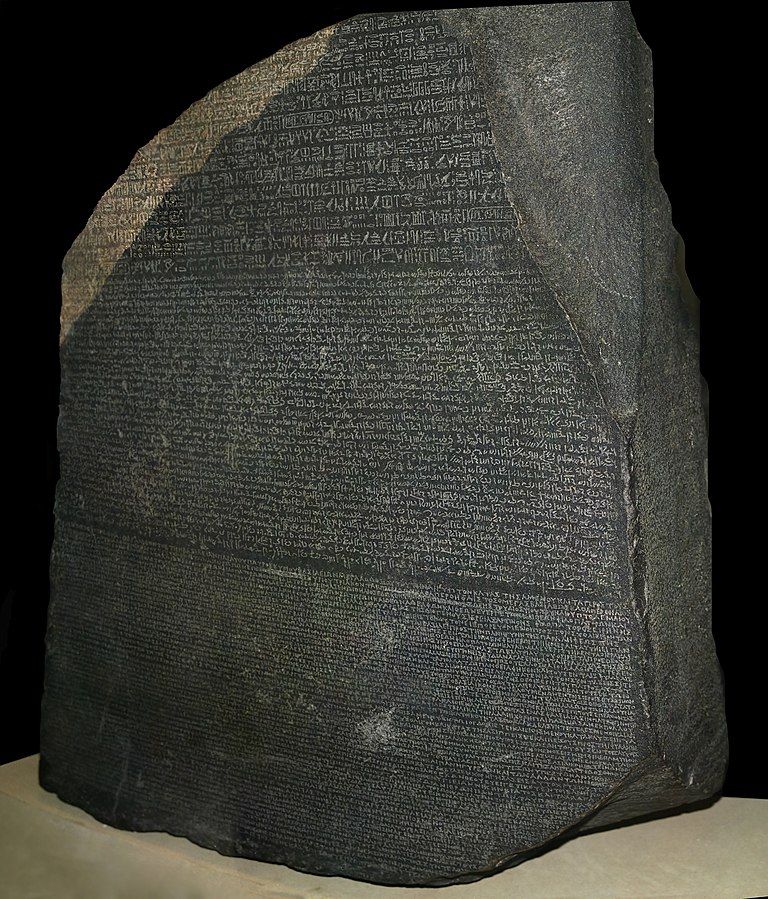

Omnilingual

"Omnilingual" may be the best single introduction to Piper's work for a contemporary audience. The story occurs in a mostly academic setting, albeit "in the field", with an active supporting cast of engineers, technicians, and soldiers who have accompanied the first expedition to Mars.

It features a female protagonist in an entirely bloodless status conflict with a credit-stealing male colleague, but has no romantic subplots involving either protagonist or antagonist. Piper had a bigger range as an author than his obsessions with militaria and logistics might indicate.

The story is something of a linguistic and anthropological detective story, so I shan't give away too much here, but the payoff is worth it. Go and read it, this really is a classic.

Naudsonce

"Naudsonce" is a tale of first contact mixed with bureaucratic ambition. Much like "Omnilingual", this too is something of a detective story, as Piper tries to envision a truly alien culture that grows out of a truly alien physiology, and how the scientists of the First Federation would have dealt with that. But this time Piper has also imagined what would have happened if the technological competence of the mid-twentieth century Americans went out to the stars possessed of the civilizational self-confidence and high-minded benevolence of the Victorians.

That benevolence will be tested by the unforeseen consequences of two utterly unlike peoples coming together for the first time. Piper was too well-versed in history to write an ending to this that is unambiguously positive, but neither did he seek to identify villains here: there really were only the best of intentions combined with considerable cultural sophistication. It is just that isn't always good enough.

Oomphel in the Sky

Piper was not a religious believer, and there is no significant place for organized religion in his Terro-Human future history. He definitely did not support Toynbee's contention that the primary end of civilizations was to produce a distinctive religion.

Yet, for all that, I find his moral vision generally sympathetic with mine, more so than some ostensibly Christian authors. Maybe the reason for that is organized religion in the mid-twentieth century had so often become the outward appearance without the inward disposition. Much like with the hilariously childish idea of God that some internet atheists reject, I too find the institutional Christianity of that era conspicuously lacking.

"Oomphel in the Sky" is a story not just about religion, but about a millennial religious movement that is threatening to spiral out of control. The setup for all this is a planetary government dominated by some rather doctrinaire Marxists from a certain university back on Earth who have no ability to deal with the geometric progression of a movement that will end up being the death of all the local humans when the kind of food that humans can digest gets burned up in a flagration of ecstasy.

Another item of note here is the POV character and protagonist is the owner of a news company, from a time before the current conjunction of journalism with the nexus of state and non-state actors that define the current ruling coalition. Miles Gilbert, the son of a very successful colonial trader, knows and respects the locals far better than the colonial administration does, but things get real interesting when Gilbert proposes a religious solution to a religious problem (a political one too, but in this case politics is downstream of religion).

Graveyard of Dreams

This story is a version of what can be found in the novel The Cosmic Computer. I haven't read the novel yet, but Carr says there are a few key differences between the two versions, including details about the Systems States Alliance that do not exist in any other of Piper's stories.

The fountains are dusty in the Graveyard of Dreams;

The hinges are rusty and swing with tiny screams.

...

We sit in the twilight, the shadows among,

And we talk of the happy days when we were brave and young.

Piper's reading of history gave him a keen sense that the fortunes of colonies could rise or fall with economic shifts driven by forces entirely external to any particular colony. Poictesme (a James Branch Cabell reference) has not necessarily done worse or better than other colonies in the grand scheme, but at the time of "Graveyard of Dreams" is in a pronounced economic slump, without good markets for the goods and materials it can produce.

Yet, there is vitality left in the peoples of Poictesme, who conspire to reverse their fortunes, concocting a plan to identify the location of a treasure, a pearl of great price, that will give them the ability to control their own destiny. We come in to the story at the penultimate moment, as eager as the conspirators to see what has come of their efforts.

Again, this is good enough to leave at that, you should read this for yourself.

What I noticed about "Graveyard of Dreams" is how the setup would make for a really great setting for Traveller, or maybe a Traveller/AD&D 1st edition mashup where you added in fantastical monsters and unholy demons to a backwater decaying planetary system to provide extra challenges to the bold young men seeking their fortunes in the Graveyard of Dreams.

Opportunity abounds on Poictesme, for those who can seize it.

When in the Course–

Carr says that this story was unpublished until included in this 1981 Ace paperback. In broad outlines, it is Lord Kalvan, without Lord Kalvan. The same setting is used, with the same major players, and even the broad outline of events is the same. Just no Calvin Morrison, formerly of the Pennsylvania State Troopers.

Lord Kalvan of Otherwhen was my introduction to Piper's work. I am almost a little surprised that I might like this version the same idea better. Whereas Lord Kalvan was set in Piper's Paratime setting, multiple Earths following different courses of history in a probabilistic fashion, "When in the Course–" is a part of the Terro-Human future history, with space faring humans exploring their galaxy.

This significantly simplifies one of the major challenges facing stories like Lord Kalvan or Lest Darkness Fall: how much knowledge can one man actually have in his head, and then not only remember but manage to successfully re-create that technology using the people and tools to hand?

When you arrive in a space ship with machine shops and stores of modern materials and a database of plans, all of that becomes straightforward. The story then turns on the political plans and alliances of the spacemen. It also allows for a broader cast of characters to play their roles in what unfolds. For Lord Kalvan, everything has to revolve around him. Kalvan delegates and instructs, but he is the fundamental source of everything. That doesn't have to be so when a spaceship full of people shows up.

I had long assumed that Lord Kalvan of Otherwhen was Jerry Pournelle's primary inspiration for Janissaries, but now I start to suspect it might have actually been "When in the Course–". John Carr says in the preface to this story that Pournelle told him about this story a couple of years before the publication of Federation, which would make some sense with the 1979 publication date of Janissaries, and the 1981 date of Federation.

That is of course a bit speculative on my part, but I think that is all part of the fun.

This was a fantastic collection. Carr curated two other collections of Piper's short stories for Ace Books in the early 80s, so I will likely look for those as well. It appears that most or all of Piper's work has fallen out of copyright, you can find free versions of just about anything, but I do like Carr's introductory material, as it gives a bit of context to Piper's work.

Piper deserves to be better remembered.

With Both Hands Classics | My other book reviews | Reading Log

Mini-reviews

Buy Federation from Abebooks Affiliate Link

Comments ()