Chesterton: Introduction to the Book of Job

A perhaps unexpected source of my style of book criticism, and how I understand popular adventure stories, can be found in G. K. Chesterton's essay "Introduction to the Book of Job".

This is an explicitly theological investigation of one of the most mysterious and allusive books in the Old Testament, and yet it contains a number of reflections on stories as such, because that is how Chesterton approaches the Book of Job.

The very first thing Chesterton addresses is the unity of pre-modern stories, with various parts being written by different people at different times. Yet, he insists that this does not compromise the unity of these works, and I wholly agree:

Controversy has long raged about which parts of this epic belong to its original scheme and which are interpolations of considerably later date.

...

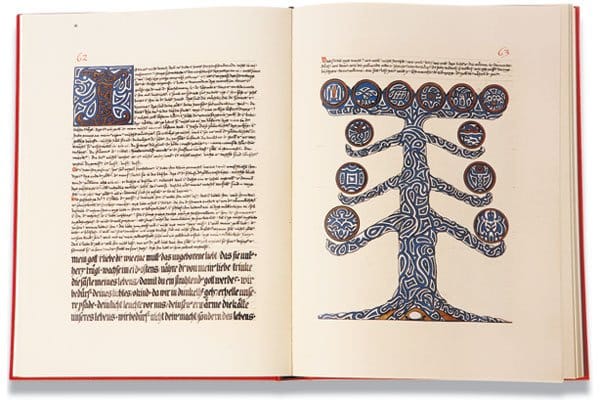

But whatever decision the reader may come to concerning them, there is a general truth to be remembered in this connection. When you deal with any ancient artistic creation, do not suppose that it is anything against it that it grew gradually. The book of Job may have grown gradually just as Westminster Abbey grew gradually. But the people who made the old folk poetry, like the people who made Westminster Abbey, did not attach that importance to the actual date and the actual author, that importance which is entirely the creation of the almost insane individualism of modern times.

...

But the thing really to be remembered in the matter of the Iliad is that if other people did interpolate the passages, the thing did not create the same sense of shock as would be created by such proceedings in these individualistic times. The creation of the tribal epic was to some extent regarded as a tribal work, like the building of the tribal temple.

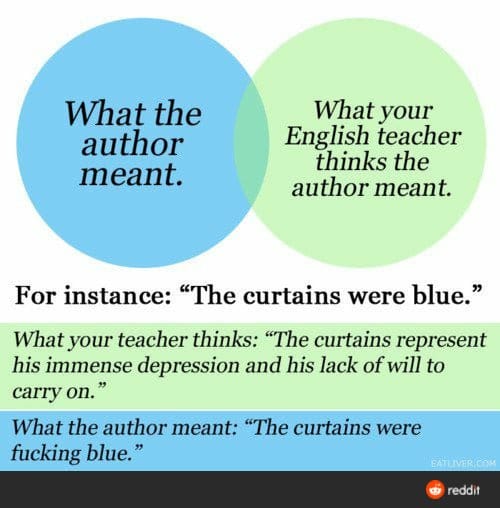

It does of course outrage our contemporary sensibilities, which put much emphasis on the individual intent and craft of the author of a story, but one of the things I took away from this is that it is possible for a story and its characters to have an essential unity independent of the author. The form and structure of the story impose certain things upon it, which the author cannot truly ignore.

For example, I think this helps explain why two of the most popular fantasy authors of the last twenty years, Patrick Rothfuss and G. R. R. Martin, have not finished their works. Each of these authors, in their own ways, tried to write a romance that undermined the concept of a romance. And each of them seems to have come to a point where they could no longer continue their stories without doing violence their own self-conceptions of being good artists.

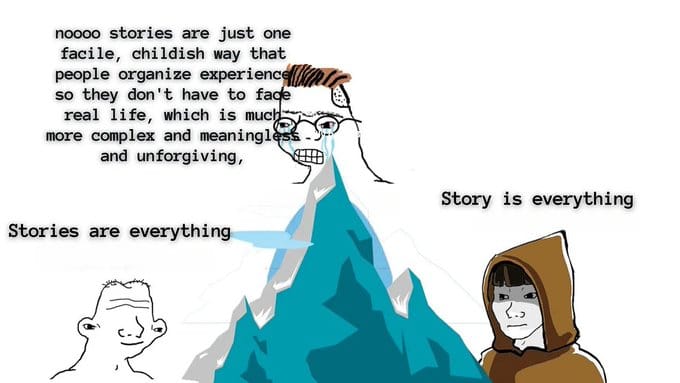

I am not here arguing for the thoroughly modern concept of the death of the author. That concept is just as individualistic as what it attempts to overthrow, simply substituting the reader as primary determiner of meaning. No, what Chesterton has said here, is that a story can have a meaning bigger than either the author or any individual reader or listener, that it is inherently a collective enterprise.

I think Chesterton is also not arguing that the meaning of a book or a story is a kind of Platonic essence or Jungian archetype, a truly independent thing that is more real than we are. Stories are things we tell ourselves, and are thus creations of our minds.

This argument is then extended when Chesterton talks about the remarkable subtlety hiding behind the simplicity of pre-modern stories:

This we may call the third point. Job puts forward a note of interrogation; God answers with a note of exclamation. Instead of proving to Job that it is an explicable world, He insists that it is a much stranger world than Job ever thought it was. Lastly, the poet has achieved in this speech, with that unconscious artistic accuracy found in so many of the simpler epics, another and much more delicate thing. Without once relaxing the rigid impenetrability of Jehovah in His deliberate declaration, he has contrived to let fall here and there in the metaphors, in the parenthetical imagery, sudden and splendid suggestions that the secret of God is a bright and not a sad one – semi-accidental suggestions, like light seen for an instant through the crack of a closed door.

...

Nothing could be better, artistically speaking, than this optimism breaking though agnosticism like fiery gold round the edges of a black cloud. Those who look superficially at the barbaric origin of the epic may think it fanciful to read so much artistic significance into its casual similes or accidental phrases. But no one who is well acquainted with great examples of semi-barbaric poetry, as in The Song of Roland or the old ballads, will fall into this mistake. No one who knows what primitive poetry is can fail to realize that while its conscious form is simple some of its finer effects are subtle. The Iliad contrives to express the idea that Hector and Sarpedon have a certain tone or tint of sad and chivalrous resignation, not bitter enough to be called pessimism and not jovial enough to be called optimism; Homer could never have said this in elaborate words. But somehow he contrives to say it in simple words. The Song of Roland contrives to express the idea that Christianity imposes upon its heroes a paradox; a paradox of great humility in the matter of their sins combined with great ferocity in the matter of their ideas. Of course The Song of Roland could not say this; but it conveys this. In the same way, the book of Job must be credited with many subtle effects which were in the author’s soul without being, perhaps, in the author’s mind.

One of the lessons I learned here is that explicit complexity and challenging works of literature are not necessarily the height of the author's craft, nor the only place where the most profound insights are to be gained.

The Song of Roland, one of the most influential examples of the chanson de geste, is a very simple work. But complexity is not subtlety. One of the things that I do here is look for the subtlety that can be found in romances, those tales of fantastic adventure that are today sold under the labels of science fiction, fantasy, or horror.

But at the same time, I defend the works that are genuinely simple, again following Chesterton.

…people must have conversation, they must have houses, and they must have stories. The simple need for some kind of ideal world in which fictitious persons play an unhampered part is infinitely deeper and older than the rules of good art, and much more important.

I believe that you don't need to write a fancy-pants story to have something to say. And I also want people to have stories that are fun. That intersection where something truly sublime results is what I look for most.

Comments ()