The Long View: The Red Book Liber Novus

The Red Book Liber Novus

I can't add anything to this. Enjoy.

The Red Book

Liber Novus

By Carl Gustav Jung

Edited by Sonu Shamdasani

Preface by Ulrich Hoerni

Translated from the German by

Mary Kyburz, John Peck &

Sonu Shamdasani

2009, W.W. Norton & Company

Philemon Series

416 Pages US$122.85

ISBN 0393065677

----------------------------------

An Actively Imagined Review

By John J. Reilly

---------------------------------

Most Respected Dr. Jung,

All of us here at Numinous Books were delighted to learn of the movement of your spirit in favor of the publication, almost fifty years after your passing, of what you called The Red Book or Liber Novus, the “New Book.” The Bollingen Foundation had long since completed the publication of your Collected Works. The matter of your unpublished work fell to the Philemon Foundation, in collaboration with your heirs. The Red Book was the largest piece of unfinished business, one that you were reluctant to present to the general public in your lifetime, but which was by no means a secret in the Jungian community; elements of it were already in limited circulation. We are pleased to report that we have succeeded in inspiring the proper parties among the living to bring this work to the light of day. Publication was preceded by a tasteful but effective publicity campaign, including the inevitable viral marketing.

During the course of your life from 1875 to 1961, you devised a model of therapy that required the reconciliation of the conscious mind with elements of the psyche of which the individual might not be aware or which were found intolerable. In this project you were at first Sigmund Freud's protégé and collaborator, but later a sort of ideological adversary. Like Freud, you held that some of the troublesome psychic material could be experiences that an individual has repressed, has tried not to know. You went beyond Freud, however, by insisting on the existence of supra-personal psychic elements, of a collective unconscious in fact, with which the ego must be reconciled for its own peace and ability to function in the human world.

Your view of history was the fundamentally Stoic vision of Eternal Return. You shared the view with Nietzsche that everything external has already happened before, but perhaps avoided the nihilist implications of that idea with the intuition that the internal is always new. Be that as it may, you had quite a lot of subtle influence on the apparent novelties of the external 20th-century. Certainly you have had more influence than did esoteric Tradition, whose precepts have many points of contact with your own but whose exponents charge you with spirit-destroying congress with the dead. The happy accident, if you believed in accidents, of your birth in neutral Switzerland may have been no small advantage in the first half of the 20th century (unlike poor Freud, with his base in disaster-prone Austria), if only because it allowed your work to assume the disinterested tone of a species of the perennial philosophy. Many of your century's most interesting artists and writers were influenced by your ideas, even if they were not necessarily actually Jungians. The same might be said of your connections with the Anglophone intelligence services, notably your long association with the Dulles family.

The Red Book is most important, perhaps, because it will clarify the identity of your teaching as a post-religious apocalyptic doctrine, a genre in which the 19th and 20th centuries were peculiarly rich. As you tell us yourself, you created the book because of visions and presentiments of disaster and carnage you began to experience around 1913. At first you supposed these to be precursors of an impending personal breakdown. When the First World War began, however, you understood them to reflect disruptions in the collective unconscious. The World War itself was only the outer manifestation of that inner turbulence. The commotions of the 20th century were caused by the failure of the Christian psyche to assimilate evil. Consequently, evil grew in the psychic shadow of Europe, whence it was projected onto national and class enemies.

All of this, you would explain with due tact in any suitable venue, was just a consequence of the passing of the Christian Age. Sometimes you expressed this change of dispensation in terms of the ending of the astrological age of Pisces, and sometimes in terms of the end of the Second Age of Joachim of Fiore. In any case, the myth of the God who saved the world by assuming the suffering of all individual men was losing its hold on the European mind. This meant disaster, since whatever novelties might be victorious in the conscious mind of Europe, Europeans still had a Christian psyche. The ghosts of Europe therefore could not rest, a proposition you showed little sign of meaning metaphorically. Your Red Book, like the Liber Inducens ad Evangelicam Aeternam of the Fraticelli, would thus be the evangel of the New Age. But let us review the structure and content of The Red Book itself now.

* * *

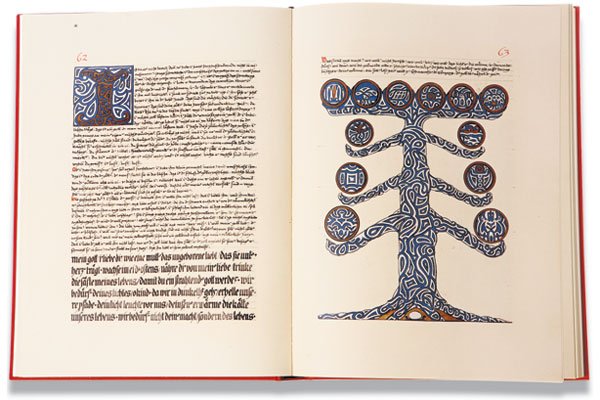

One of your oft-cited principles is the phenomenon of enantiodromia, which means that the excess of any force or tendency generates its opposite. We see that in the publication of your book: in an age when physical books are disappearing into cyberspace and their contents being viewed on handy plastic tablets, this book at about a foot wide by a foot-and-a-half long is so large and heavy that it can be read comfortably only if mounted on special furniture. The redness of the more informal title comes from the cover of the original. From 1914 to 1930 you recorded your dreams and visionary stories in a sort of italic book-hand, punctuated by illuminations and other graphics. These range in quality and style from naïve outsider art to intriguing mosaic and geometrical abstractions. Anyone familiar with your work has already seen some of these images, but The Red Book could launch your belated reputation as an artist. The graphics and even the text are almost devoid of explicit sexual references, by the way. Freud would have something to say about that.

The bulk of the published volume consists of your own illuminated calligraphic volume, divided into “Liber Primus” and “Liber Secundus,” the latter much longer than the former. The single largest item that does not consist of photographic reproductions is the English translation. (The German version of the book, incidentally, which presumably has a transcription rather than a transliteration, is a bit briefer but costs twice as much.) The critical additions include a biographical sketch in which you would find nothing awkward, as well as an able description of your system by the principal editor and translator, Sonu Shamdasani. The book ends with a final section, “Scrutinies,” including the previously published “Seven Sermons to the Dead.” There is an Epilogue containing some short pieces in your usual academic style. They and Scrutinies give a very detailed description of the cosmology underlying your psychological system, including the theology, or metaphysics, or whatever you prefer, concern the God Abraxas.

Liber Primus and Secundus are made of relatively short chapters with titles like “The Desert,” “The Murder of the Hero,” and “The Magician.” Here is a bit of “The Desert” from “Liber Primus.”

Sixth night. My soul leads me in the desert, in the desert of my own self. I did not think that my soul is a desert, a barren, hot desert, dusty and without drink. The journey leads through hot sand, slowly wading without a visible goal to hope for? How eerie is this wasteland. It seems to me that the way leads so far away from mankind. I take my way step by step, and do not know how long my journey will last.

As literature, this compares unfavorably to Khalil Gibran, but that is a bit unfair. Particularly in the earlier parts of the book, you are doing something very close to automatic writing. The unconscious is invited to speak for itself. The book in some parts echoes Luther's Bible (which inevitably produces an echo in the English translation of the King James Bible), in some parts it resembles Nietzsche's parody of Luther in Also Sprach Zarathustra, and in others Goethe's Faust Part II. You yourself, of course, believed that those works by Nietzsche and Goethe were written in the same way as The Red Book, by interrogation of the deep psyche. Some of your readers will no doubt be reminded from time to time of Hesse's Steppenwolf. In any case, in the manner of these works, you alternate prophetic discourses with passages that must be considered whimsical, like this from Liber Secundus:

S[oul]: “Have you got hold of him?”

I: “Welcome, hot thing of darkness! My soul probably pulled you up roughly.”

S[atan, here and hereafter]: “Why this noise? I protest against this violent extraction.”

I: “Calm down. I didn't expect you to come last of all. You seem to be the hardest part.”

S: “What do you want from me? I don't need you, impertinent fellow.”

I: It's a good thing we have you. You're the liveliest thing in the whole dogma.”

S: “What concern is your prattle to me? Make it quick. I'm freezing.”

I: “Listen, something has just happened to us: we have united the opposites. Among other things, we have bonded you with God.”

S: “For God's sake, why this hopeless fuss? Why such nonsense?”

I: “Please, that wasn't so stupid. This unification is an important principle. We have put a stop to the never-ending quarreling, to finally free our hands for real life.”

S: “This smells of monism. I have already made note of some of these men. Special chambers have been heated for them.”

I: “You're mistaken. Matters are not as rational with us as they seem to be. We have no single correct truth either. Rather, a most remarkable and strange fact occurred: after the opposites had been united, quite unexpectedly and incomprehensibly nothing further happened. Everything remained in place, peacefully yet completely motionless and life turned into a complete standstill.”

Jungians to this day have a sense of humor not always to be found among Freudians. Or indeed elsewhere.

The reconciliation of psychic opposites, of instinct and reason, of male and female, of good and evil, occurs by creating a conscious relationship with the collective psychic structures. These are the archetypes. In their most familiar forms, they turn up as the story templates for characters in popular fiction, from the young hero who rises from obscurity to save the world, to helpful talking animals (the latter recently tend to be helpful talking robots). The archetypes are also the foundations of the great characters of myth.

Throughout the book, but especially in Liber Primus, you talk to your soul. The soul is revealed to you by the cultivation of your anima, the minor-key female side of yourself, which is also a manifestation of the more basic reality of Eros. (Women, of course, have an animus.) The soul links the personal with the collective; it becomes for the ego the symbol of the psyche. You speak also to the Logos, enigmatic reason, which has its own motives and its own life, but which it is a necessity of mental health to reconcile with Eros. You remind us that the archetypes are multiform. The pair of Logos and Eros appear frequently in myth and fiction, right down to stories that involve a mad scientist and his daughter. In this book, they appear at first as Elijah and Salome, who of course do not appear in the Bible together, but the venerable Elijah seemed to you a better representation of Logos than would John the Baptist. The pair also appear as the more or less historical couple, Simon Magus and Helen; the former rescued the latter from prostitution because she incarnated Sophia, divine Wisdom. Your mature image of this relationship is Philemon and Baucis, who appear in a Greek myth about the happy fate of those who offer hospitality to the Gods unknowingly. (“God” is almost always capitalized in this book, by the way; an echo of the German practice with all nouns, perhaps). Philemon became an important figure in your life, almost a personal prophet. The Red Book uses the Greek spelling of the name: ΦΙΛΗΜΩΝ.

Conventionally religious people might object that what you teach your followers to do would be the worst kind of prayer. Prayer, however, is not what is intended. This process of active imagination that you use in interacting with the archetypes is familiar to many writers of fiction. You solidify psychic entities with whom you may then converse like a novelist talking to his characters. To the extent the characters are the forms of activated archetypes, however, they are not wholly of your devising, and they are not entirely under your control.

The collective unconscious as you describe it is not merely a standard unconscious that everyone has, like a standard pulmonary system. Rather, it is a networking the whole human race, present and, to some degree, past. Thus, you understood that the assassination of poor Archduke Ferdinand was not merely an attack on a high-status person, but part of a general movement of the European spirit to kill the hero within.

You popularized the hypothesis that the collective unconscious is exterior to individual humans in uncanny ways. Coincidences occur, the famous “synchronous events,” when the archetypes are activated, thereby enabling them to make an impression on an otherwise inattentive ego. The collective unconscious, as you were never slow to acknowledge, bears a family resemblance to Immanuel Kant's “noumenon,” the dark subsurface of the knowable world, a darkness where causality does not apply. Physicists of the caliber of Wolfgang Pauli have attempted to explain the phenomenon, even if its reality has never been satisfactorily demonstrated except to those who have experienced it. The “quantum entanglement” of the Copenhagen Interpretation of quantum mechanics is still sometimes mentioned in this connection. That is hardly surprising; the Copenhagen Interpretation is just Kant without the Hilbert space.

Objective observers, if there are such creatures, would be forgiven for suspecting that your invocations of science were just a patina of modernity that you applied to a system that you knew quite well was a kind of magic. Magic of some sort is necessary to deal with the collective unconscious, though even magic cannot control it. The collective unconscious deploys that weapon first, of course. It appears as the uncanny and at first glance inexplicable glamour that for your patients attached to certain people and things. Jungian analysis is about coming to terms with that glamour, especially if it inhibits life and growth.

For your true adepts, the point of all this is “individuation,” the formation of the Self around which the elements of the psyche revolve like the planets about the sun. The Self is emphatically not the ego. Should the ego identify with the Self, or with any of the archetypes, it becomes divine in a pathological sense.

* * *

Let us return to one of the key features of this book, that it falls into the genre of apocalyptic prophecy. The meaning of the religion of every age is the religion that succeeds it: so says the psychic entity that appears in the Liber Secundus under the name “The Anchorite.” (Readers may be confused about how seriously to take this figure, since his personality later deteriorates and he becomes interested in liturgical reform, particularly liturgical dance.) In any case, the religion of the New Age would be a kind of depth-psychology monotheism, with the Self at the center of every individual recognized as identical (and not merely very similar) to the Self at the center of every other individuated individual. On the other hand, it would be an age of polytheism, since the archetypal complexes of the collective unconscious are real Gods. It would, however, be singularly dangerous to worship them; that would invite possession. As for the divine of the old dispensation, it apparently has an honorable retirement to look forward to, if this passage near the end of the Scrutinies is to be believed. Here you show us what seems to be Jesus talking to a later version of Simon Magus:

ΦΙΛΗΜΩΝ said, “You are, Oh master, here in the world of men. Men have changed. They are no longer the slaves and no longer the swindlers of Gods and no longer mourn in your name, but they grant hospitality to the Gods. The terrible worm came before you, whom you recognize as your brother insofar as you are of divine nature, and as your father in so far as you are of human nature. You dismissed him when he gave you clever counsel in the desert. You took the counsel, but dismissed the worm: he finds a place with us. But where he is, you will be also. When I was Simon, I tried to escape him with the ploy of magic and thus I escaped you. Now that I gave the worm a place in my garden, you come to me.”

The religion of the New Age follows the Pleroma's tendency toward individuation. The collective savior is no longer possible because each person must become his own savior. The soul can no longer identify with the collective Christ archetype.

Late in the book, you, or the archetypes who speak through you, reveal that the essential stuff of reality, or the perfect vacuum in which reality shimmers, is the Pleroma, the fullness. It is simple, in the sense of perfectly uniform; a sea of unrealized possibility. The first emanation of the Pleroma is Abraxas, the lord of the material world. He is a time God: his name is a nonsense word that simply incorporates the numerological value “365.” He is neither good nor evil, but effective cause of the horror of history and its wonder. His creations are God (or “Helios,” as you prefer) and the devil. Abraxas should not be worshipped, you caution, but neither can he be neglected. Within each psyche, your readers are promised, the Self can become Abraxas to the rest of the psyche's contents, including to the ego.

Readers will be confused, as may have been your intent, about whether everyone can or should seek individuation. Many people, perhaps all, seek that degree of psychological integration needed to function socially. Maybe individuation, which links the personality to cosmic forces, was for an elite? Those who achieve it would have a numinous quality marking them as unusually substantial persons. That is as may be, but surely you must question now whether your prophecy of a new spiritual regime has been fulfilled in any but an ironic sense.

You did correctly intuit that the later 20th century would see a revulsion against the collectivism that had increasingly characterized Western Civilization since the middle of the preceding century. However, the libertarian trend has been notably antinomian. Far from embracing depth psychology, it has been characterized by an ebbing of the psychic sea rather than a deepening. As for conventional religion, that too has suffered from the general desiccation, but your work has not served to drive people from traditional religion, or even in many cases to provide a spiritual alternative. Rather, it has served as a bridge to systematic spiritual examination for people who otherwise would not have been able to approach the question seriously. People who do this are likely to find the transcendent God at least as interesting as the immanent God. Often enough, they find that not all spiritual entities are really the fauna of the psyche, even of the collective psyche.

That is none of our affair, of course. We just publish this stuff.

With friendly greetings,

Basilides Screwtape

Numinous Books

Developmental Editor

Copyright © 2010 by John J. Reilly

The Red Book (Philemon) By C. G. Jung

Comments ()