Fixing Herbert's Mistake

I came across this article yesterday about how there is an opportunity with Denis Villeneuve's Dune: Part Two to "fix" Herbert's mistake. That was a bold enough statement to give me an opportunity to explore what Frank Herbert was doing with Dune.

The way Paul was built up in the first Dune movie sets him up to display his true powers as the Kwisatz Haderach and a relative messiah to the Fremen in Dune: Part Two. That said, his inability to control the effects of the Jihad undermines this hugely, and the movie format would not allow enough scope to resolve this effectively. Though it would undoubtedly be an enormous change, altering how the Jihad plays out in the wake of Paul's victory could help him retain his core characteristics in the eyes of the viewer. In any case, the practicalities of the situation may make this a necessity rather than a choice based on artistic license.

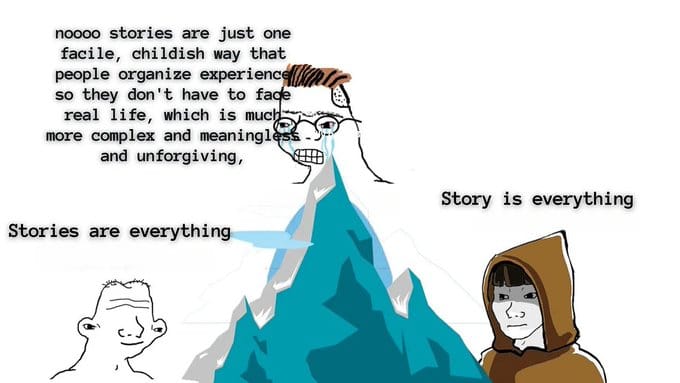

This is a misunderstanding, but I think an understandable one. Herbert did set up Paul to be a messianic conquering hero. But to understand the theme of Dune we need to see Paul get everything he wants, and then hate it.

Dune is an typical adventure story, insofar as it really does have an arc consisting of the unjust death of a father, followed by the son working out his revenge from the shadows. It ends with the bad guy getting dead, and the hero marries the princess. But this is not happily ever after; everything is shot through with sadness.

We don't need to fix Herbert's mistake by making Paul an uncomplicated conquering hero. We already have that story. It's A Princess of Mars. Dune is a deconstruction of Burroughs' planetary romance about a man who conquers a desert planet by becoming the hero they thought was a myth.

We *do* need a movie version of A Princess of Mars that is as thematically appropriate as Villeneuve's Dune. The recent Disney version looked good but lacked heart, or understanding of the character of John Carter.

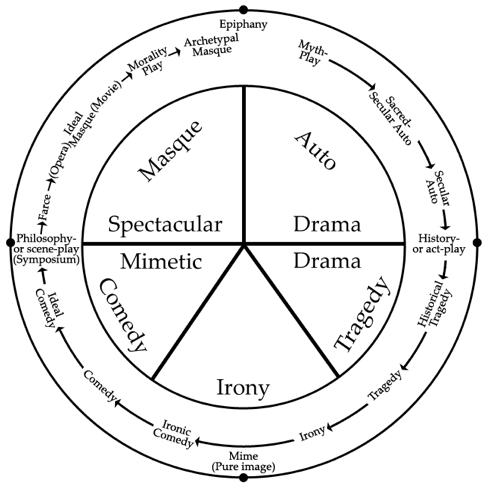

If you want to understand Dune, you need to understand what Burroughs was doing in A Princess of Mars and its sequels. A Princess of Mars is a romance, and a comedy. A romance is a series of wondrous adventures. A comedy is a newborn society rising in triumph around a hero and his bride:

Comedy, however, is based on the second half of the great cycle, moving from death to rebirth, decadence to renewal, winter to spring, darkness to a new dawn

Mars is a dying world, and John Carter brings it new life by his union with Dejah Thoris. Dune is the antithesis of this, the opposite part of the cycle Frye spoke of.

The first half of this cycle, the movement from birth to death, spring to winter, dawn to dark, is the basis of the great alliance of nature and the sense of nature as a rational order in which all movement is toward the increasingly predictable . . . the pervading feeling is of something inevitable working itself out

Dune is an adventure, but it is also a tragedy. This is harder to see if you only read the first book, or see the first movie of this most recent adaption. Oftentimes in tragedy, triumph and defeat are in fact the same thing considered from different points of view, and that is what we see here.

Paul Atreides, the product of thousands of years of eugenics, a man who can literally see the future, cannot avert the disaster he not only sees coming, but creates through his own actions. In a way, Paul achieves everything he aims to do; the cost is only everything.

If Dune were the adventure suggested in the original post, then the protagonist would not be Paul, but Leto. Leto is the best man in the aristocratic Landsraad assembly that comprises one of the three pillars of Dune’s futuristic society.

If it were a comedy, then Leto and Jessica's love would restore their civilization. But that isn't what Herbert wanted to do.

Duke Leto represents a more humane future for the Imperium, one that will never be because the best man, in ordinary terms, is simply inadequate to the task. Despite being an enthusiastic participant in the Byzantine politics of the Imperium,

Leto cannot see just how devious and depraved his enemies are because of his essential nobility. Leto is loved by his peers and his subordinates for that nobility; even the Padishah Emperor who allies with the grasping Baron Harkonnen to destroy Leto wishes that Leto was his son.

This is of course possible, because despite Leto’s love for Paul’s mother, she is officially a concubine, in order to allow precisely the kind of Habsburg-style political marriage that could have made Leto the Emperor’s son.

Thus Paul is both greater and lesser than his father. Greater, because he can revenge the death of his father and frustrate the wicked schemes that brought Duke Leto down, but lesser because Paul is not loved by his followers, but worshipped instead.

Paul lost the nobility and magnanimity of his father. This theme runs even to the relationship between Paul and his mother, the Lady Jessica. Jessica is disturbed at what Paul has become, while Paul is resentful at what he has been made to be. And like his father, but at the same time disturbingly unlike, Paul must put aside the woman of his heart in order to allow for a dynastic marriage.

All this is setup in the first book! But you have to look to see it. When the jihad scorches the universe, that is something inevitable working itself out.

Comments ()