Lay the Hate: Forgotten Ruin Book 4 Review

Lay the Hate is the fourth book in the Forgotten Ruin book series, Jason Anspach and Nick Cole’s prose poem to the Rangers and D&D. [Amazon link] In book four, the Rangers decide to get into the domain-level game, Talker has an urban adventure, and the best of plans are waylaid by an unfortunate wilderness encounter. If you understood all that, you should just go buy this book. If you did not, allow me to explain.

Lay the Hate: Forgotten Ruin Book 4 by Jason Anspach and Nick Cole WarGate Books (September 1st, 2021)

However, in order to do so, we are going to need to take a detour into D&D internet sub-cultures. Trust me, this will be worth it.

Part of the magic of Forgotten Ruin is its juxtaposition of the brooding machismo of the Rangers with the utterly dweeby conceits of tabletop roleplaying games. That this works so well, when it seems like it should not, tells us something. In its current state D&D has lost touch with its roots in stereotypically masculine pursuits such as wargaming and an obsession with history. A largely Twitter based movement called the BROSR has arisen to join together what time and chance have sundered.

I’ve talked before about the OSR, a Biblicist back-to-the-texts type movement of the early 2000s that attempted to recover the early magic of D&D from forty years ago. Some real fruit came out of that, but the movement petered out as it became lost in the attempt to make money selling systems and supplements, an example of Emperor Norton’s thesis that social media has distorted artistic communities by turning hobbies into businesses.

The BROSR is very much a movement of the current moment, saturated in memes, deliberately performative in the manner of professional wrestling, and utterly without respect for anyone or anything. It is also very funny, so long as you can stand their style of humor. A major part of the BROSR message is that long-neglected parts of the infamously complicated and baroque AD&D 1st edition rules work together to create a more interesting, more enduring, and more flexible style of game.

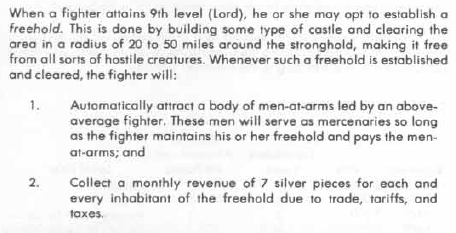

One of those elements is known as the domain game. The domain game comes from a provision in the AD&D rules that certain classes attract followers at a certain level, and may also construct a stronghold. Construction of a castle or tower or religious sanctuary allows a player to control a “domain”, to collect taxes, and to have standing military forces.

There are a variety of reasons this was neglected over the years. I’m sure to some the idea of administering a feudal mini-state seemed really boring. It was also notoriously difficult to raise a character to the required level in the high lethality 1st edition rules. The antiquarian interests of the OSR paved the way to recover this mode of play by looking to see what had been done before, especially the film Secrets of Blackmoor.

But the BROSR showed us how it could be done now, in the extravagantly ridiculous Trollopulous campaign. First, players could try to do anything they wanted within the game world, and so were free to start changing it in any method they could devise. You needn’t wait to establish a base of operations until the point at which you became so famous you automatically attracted followers. You can band together with other adventurers and buy something small, or find something small to call your own.

The other key recovery was the practice of allowing players to run what would normally be powerful or influential non-player characters in the campaign world. In theory, once domain play was established, this would just happen naturally, but like the in famous D&D precursor game of Braunstein, the dungeon master can create factions and their leaders and let players decide what those factions are going to do. Multiple levels of play are possible in the same campaign world, from grand strategy down to individual combat. This allows for players to have different play styles and interests in a bigger world.

Forward Operating Base Hawthorn

(from GURPS Witch World by Norton collaborator Sasha Miller and Ben W Miller, Steve Jackson Games, 1989)

So what does all this have to do with Lay the Hate? If we step back from Anspach and Cole’s characteristic grunt’s POV and look at the bigger picture, in the first book, a charismatic leader of a war band assaults and seizes a base of operations. In the second book, the company defends their base against an attempt to retake the castle. In the third, the war band’s alliance with an indigenous group is cemented by killing their ancestral enemy, which both provides security for the castle and a source of money to fund operations. This is the domain game that is hinted at in the D&D rules.

And now Lay the Hate can be situated in its context. With a solid base established, the charismatic leader, Captain Knife Hand, has gathered intelligence on the other factions in the world, and attempts to improve his strategic position by launching an expedition against a key enemy. But in a world without airplanes, that means months of travel. In the book, we never even get close to the objective the Rangers set out for, because they ran into a hostile force en route and needed to defend themselves.

This too, is a classic and often maligned D&D mechanic, the random wilderness encounter. In this kind of world, traveling takes time, and there are only a few methods for information to travel any faster than people can in the game world. The richness and dynamism of the campaign world require a fair bit of logistics to work out, and the now common practice at the gaming table of allowing the players to begin outside of wherever they were going robs the game of the texture of the world that more naturally emerges when it takes weeks to travel to a seaport and then weeks more to sail to your destination. A huge part of the story is just getting there.

Finally, the urban adventure. One way of looking at the kinds of things that can happen in a D&D game is to divide up play sessions into dungeon delves, wilderness encounters, and urban adventures. As we have seen, this only does justice to one possible level of play, but the different environments do tend to have different flavors. Since the Rangers needed to sail, they went to a seaport. And while they were preparing for their trip, Talker, our POV grunt, gets involved in some classic tavern roleplay.

This portion of the book is relatively short in the amount of space it occupies, but it looms large in the development of the story. I shan’t get too deep into it here, as I found the way Talker’s elliptical style tends to orbit around his point rather than engage with it directly enhanced the impact of this particular element. Here, the form of a novel takes pride of place. Much of the development of D&D over the last forty years has been attempts to create narratives like the one Anspach and Cole create here. I suspect that the novel is always going to win this contest, as the kind of improv theater combined with the illusion of player choice the game has settled into cannot create what you will find in the book. Read it for yourself and see. Or, wait a bit and hear the audio version performed by the exceptional Christopher Ryan Grant. This story is like the chansons de geste, meant to be performed in the firelight.

There is some pretty cool Ranger stuff that goes on in this book too, if you are into that.

I received a free review copy from the authors. Go check out their website: https://forgottenruin.com/

My other book reviews | Reading Log

Forgotten Ruin

Forgotten Ruin Book Review

Hit & Fade: Forgotten Ruin Book 2 Book Review

Violence of Action: Forgotten Ruin Book 3

Galaxy’s Edge season 1:

Legionnaire: Galaxy's Edge #1 Book Review

Galactic Outlaws: Galaxy's Edge #2 Book Review

Kill Team: Galaxy's Edge #3 Book Review

Attack of Shadows: Galaxy's Edge #4 Book Review

Sword of the Legion: Galaxy's Edge #5 Book Review

Tin Man: Galaxy's Edge Book Review

Prisoners of Darkness: Galaxy's Edge #6 Book Review

Imperator: Galaxy's Edge Book Review

Turning Point: Galaxy's Edge #7 Book Review

Message for the Dead: Galaxy's Edge #8 Book Review

Retribution: Galaxy’s Edge #9 Book Review

Galaxy’s Edge Season Two

Tyrus Rechs: Contracts & Terminations:

Requiem for Medusa: Tyrus Rechs: Contracts & Terminations Book 1 Review

Takeover

Takeover: Part 1 Book Review

Takeover: Part 2 Book Review

Takeover: Part 3 Book Review

Takeover: Part 4 Book Review

Takeover Book Review [summary for the omnibus edition]

Order of the Centurion

Order of the Centurion #1 Book Review

Iron Wolves: Order of the Centurion #2 Book Review

Stryker’s War: Order of the Centurion #3 Book Review

Through the Nether: Order of the Centurion #4 Book Review

The Reservist: Order of the Centurion #5 Book Review

Savage Wars

Savage Wars: Savage Wars #1 Book Review

Gods & Legionnaires: Savage Wars #2 Book Review

The Hundred: Savage Wars #3 Book Review

Forget Nothing

Comments ()