The Pulp Mindset: A NewPub Survival Guide by JD Cowan Book Review

For the most part, here at With Both Hands I review fiction, but since this book is about the current state of adventure fiction, it makes sense to discuss it. Major changes are underway in fiction publishing, especially in fantastical adventures marketed mostly to men, and JD Cowan is here to propel us forward with The Pulp Mindset: A NewPub Survival Guide [Amazon link].

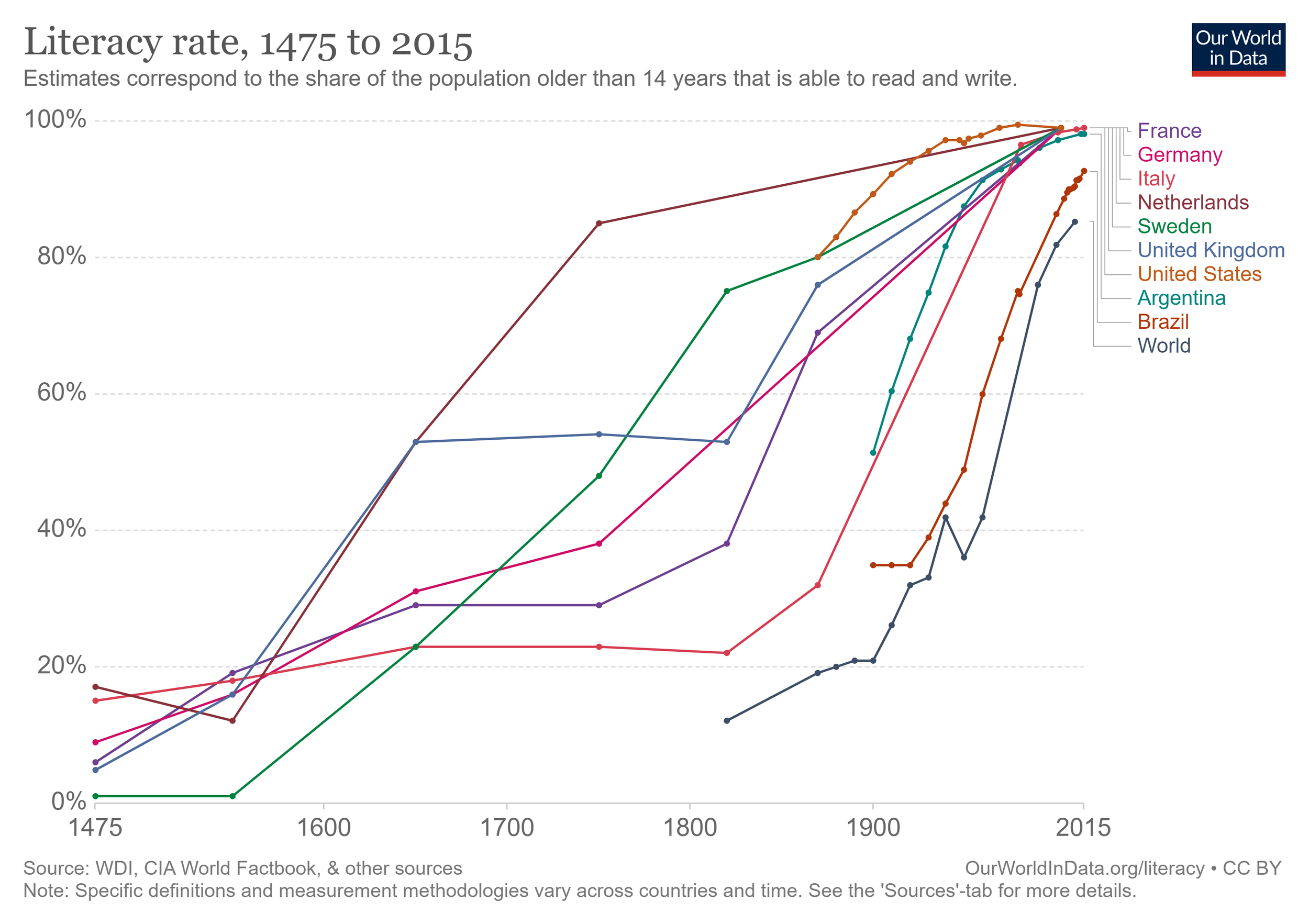

Cowan is here to offer advice on how to recover what has been lost. What, exactly, has been lost? A world were people, and especially men, read for pleasure. Marilynne Robinson wrote in The Death of Adam [Amazon link], that part of the reason that literacy was so important in nineteenth- and early twentieth-century America was that Protestantism prioritized reading the Word of God. I’m not averse to that thought, but looking at the data, nearly universal literacy [outside of groups explicitly marginalized] was present in all of Europe and most of its diaspora more than a century ago.

In late nineteenth century America, many of the bestsellers were written by women, for women. But there was a healthy market for adventure fiction for men as well. The dime novels, penny dreadfuls, and pulp magazines sold well for a long time, roughly until the middle of the twentieth century, when fiction marketed towards men went into a long decline. The Pulp Mindset isn’t primarily about the reasons for this decline, although Cowan has an illuminating series of posts on that subject that I have in the back of my mind as I review.

What The Pulp Mindset is about is: what do we do going forward? I say we, even though I am not a writer of fiction, which seems to be the primary intended audience, because I am broadly in support of Cowan’s mission to add more escapism and fun into fiction. Cowan’s prescription for doing so is to write more like authors from the Pulp Era: fast-paced action, good guys and bad guys, and above all entertain the reader.

Since I have been on a quest to familiarize myself with the Pulp Era, and also with the authors listed on Gygax’s Appendix N, I can verify that I do tend to find fiction written in the 1920s and 1930s both more exciting and more fun. Neither I nor Cowan would claim that you can’t find a good book written after that, but I would say that the proportion of fiction written that is both exciting and fun has gone down since the Pulp Era.

One of the few practical pieces of advice that Cowan gives to aspiring writers looking to restore fun to their fiction is to never violate the reader’s trust.

The rules are actually very simple. In fact, there’s only one really big law no writer should ignore: Don’t violate the reader’s trust. You can deliver plot twists to your audience; you cannot promise them an action story and then deliver a non-fiction account of dolphin riding in Florida. Give them what they came for. Subversion is not a synonym for “good” and it is about time that becomes common knowledge once more.

…

Unfortunately, many modern writers (especially in OldPub) cannot help showing how brilliant their twists are, which leaves their potentially exciting stories limp and flat with nothing to them but said shallow table flip.

…

Do not risk trying to fool your readers by deceiving them with flashy twists that undercut the beginning of the story. It will not end well for you.

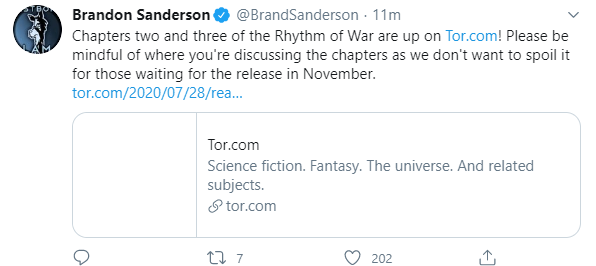

The emphasis that Cowan puts on this can be expanded upon by looking at a related phenomenon in fans: excessive fear of spoilers. I’ll illustrate this with a recent tweet from Brandon Sanderson, perhaps the last beneficiary of the system Cowan calls OldPub.

Sanderson is here giving a sneak peak of a new book of his coming out this year. He is doing his fans a favor, and also ideally gaining new fans by giving away some of his work for free as an advertisement. Yet, he feels compelled to undercut this goal by warning his readers to be mindful of actually talking about this work to people who aren’t familiar with it.

There is something special about the first time through a book you really enjoy. I wouldn’t want to take that experience away from anyone. I do question whether a book that could truly be ruined by loose talk about what happened in Chapter 2 is in fact an enjoyable book at all. The style of writing Cowan warns against, I suspect, is the root of the problem. If the only really interesting thing about your book is the clever twist, then yes, I suppose it can be ruined by spoilers.

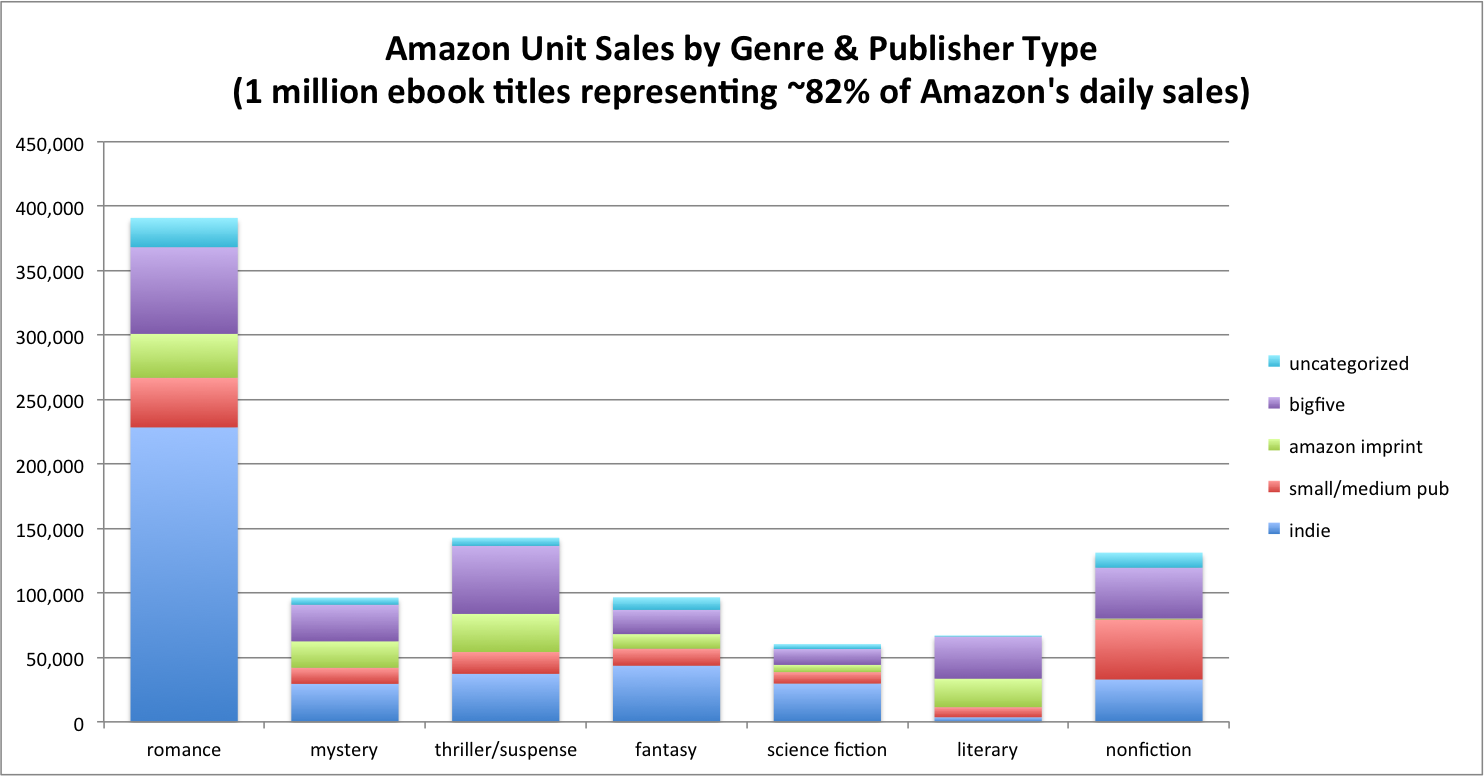

This also supports Cowan’s assertion that genre fiction in general has abandoned its audience in lieu of a captive fanbase that will simply consume any new item from a given IP. If you can’t talk about a new book or watch a trailer for an upcoming movie outside of a special forum reserved for spoilers, then you aren’t going to attract any new readers or watchers. And the sales numbers back this up. Genre fiction sells really poorly, especially compared to the Pulp Era.

Do you think the readers of romance novels care about spoilers?

I’m not going to pick on Sanderson [too much], as I have read his books and liked them, but pulpy his books are not. Will Wight also writes fantasy adventures with detailed magic systems, but writes faster, and has more interesting things happen in a single chapter than Sanderson does in whole books. And his sales are possibly as good, or better, than Sanderson, even though Wight self-publishes. Wight isn’t associated with any of the pulp restoration movements that I know of, but seems to have independently come to much the same conclusion as Cowan for what works now.

Cradle is not exactly pulp, but exciting adventures always sell well

Cowan also recommends fully embracing that adventure fiction is low art. He defines low art as:

Low art deals with visceral and tangible goals and stakes, while high art deals with ephemeral and heady concepts…If you wish to be a pulp writer, you must master the craft of low art creation.

…

If you’re reading a book by Dostoevsky or Flannery O’Connor, you are not there to be greeted with fast-paced stories of heroes shooting villains and rescuing space princesses. This sort of fiction exists for an entirely different reason than the pulps.

This is a pretty good way of looking at it, although it is of course true that many works of fiction blend the two to some degree. John J. Reilly used to define hard science fiction as a story that left the reader usefully instructed in some principle of physics or biology after reading a story that otherwise closely resembles a Western. A lot of the changes that happened in the mid-twentieth century to science fiction were attempts to change the mix of high and low art in the field by deliberately changing the balance from action and adventure to science and social reform.

Granted, this isn’t exactly what most people mean by high art, but it was definitely about ephemeral and heady concepts over the visceral. And if you want an excellent example of what it looks like when a pair of authors shift the balance between low and high art in the middle of the series, take Gods & Legionnaires by Jason Anspach and Nick Cole.

A short detour into High Art by Anspach and Cole

The book was divisive among the Galaxy’s Edge fans, with many complaints that the dream-like Gods section, a retelling of Van Vogt’s Centaurus II in the Galaxy’s Edge universe, was too hard to understand, and didn’t feature enough action. Cole and Anspach only did this once, and got away with it, but I don’t think they would have gotten as popular as they are if the whole series was like this.

I loved Gods & Legionnaires, but I also admit that my tastes are unusual, and looking back in history, as Cowan has done, should provide a cautionary tale for trying to shift the balance too much in this direction. I think there is a real temptation, a pull from authors who want to do something challenging, and a push from clever reviewers like me who love that kind of thing, but it seems off-putting to the broader audience.

That broader audience is whom Cowan is trying to serve, and in my own small way, I am too. I think aspiring authors might find some interesting inspiration from Cowan’s work, which after all mostly serves as a signpost to the successful story tellers of the past. What has worked before can work again, if you know about it. This work could be the catalyst that makes that possible.

I was provided a copy of this book by the author.

My other book reviews | Reading Log

Other works by JD Cowan

Gemini Man series

Gemini Warrior: Gemini Man Book 1

Comments ()