The Long View 2007-07-07: Summorum Pontificum

Whether Summorum Pontificum actually heralds the beginning of the Second Religiousness is, not clear, at present, but at the very least the SSPX has improved its status within the Catholic Church in the last decade.

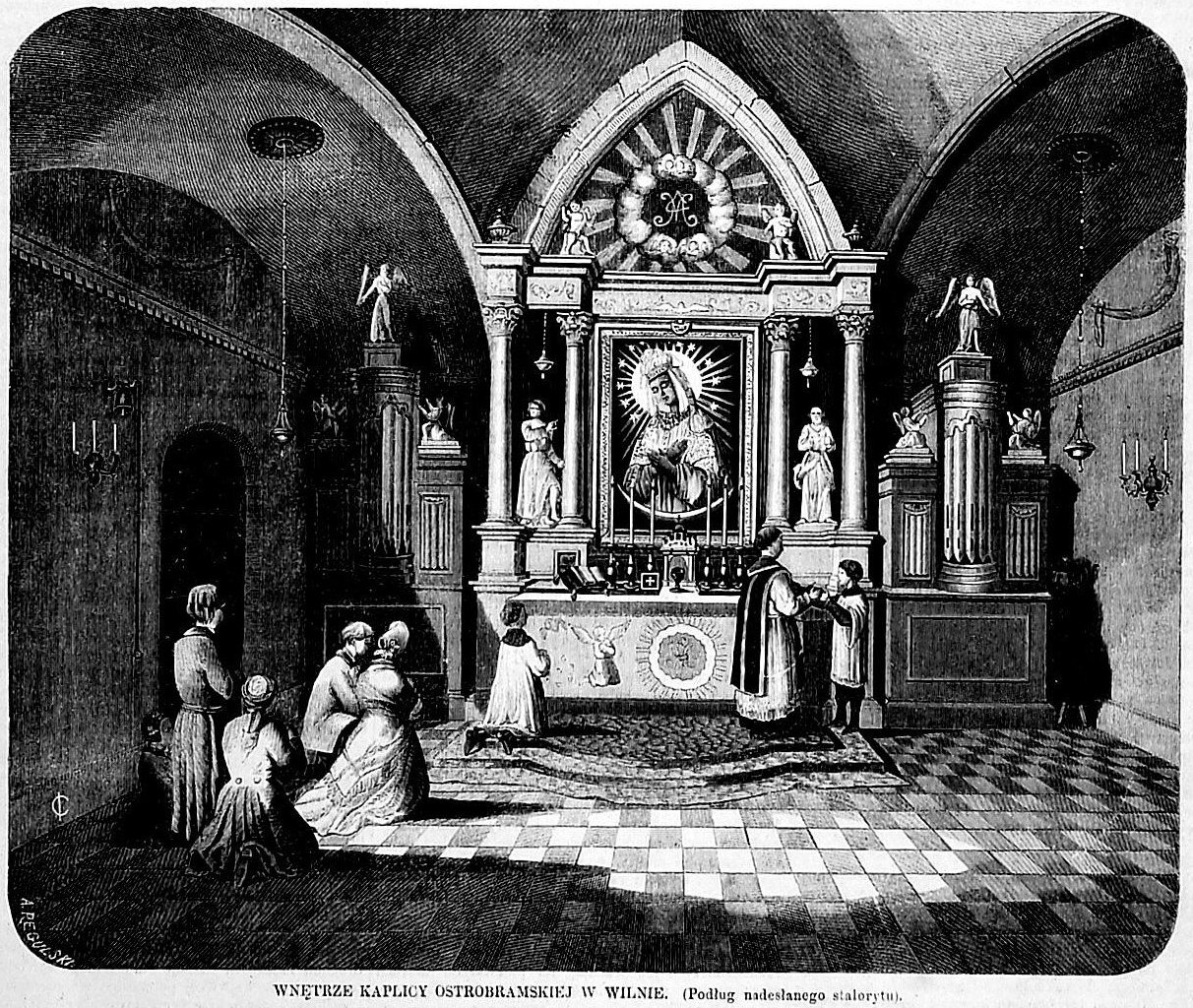

Low Mass celebrated at the Chapel of the Dawn Gate in Wilno (Vilnius). Interior in 1864.

Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=248081

Summorum Pontificum

Today is the official publication date of a document and cover letter from Pope Benedict XVI that permit the Tridentine Latin Mass to be said in any parish whose pastor approves its celebration. The document is a motu proprio, a term meaning "on his own initiative." The title is Summorum Pontificum, meaning "of the sovereign pontiffs."

The gist of it is that the Tridentine Mass now may be said without the need for special permission from the local bishop. Summorum Pontificum essentially reverses the default in this regard; such permission had heretofore been necessary. The text of Summorum Pontificum and Benedict's accompanying explanatory letter are available here on the site of the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops.

That site also includes a Question-and-Answer section from the Conference's own liturgical experts that is as hilarious an example as you will ever see of commentary written through clenched teeth. Most of the bishops don't have strong feelings on this matter. Half the bishops in the United States have in fact given permission to one or more parishes in their dioceses to use the Tridentine Mass. The network of liturgical experts and institutes, however, really, really hate the idea of the use of the old Mass, even its use as a rare treat. Their arguments are not irrational, but this is a situation where Darwin has spoken, whether or not the Holy Spirit has. The old Tridentine use is robust, perhaps more robust than the liturgical forms the liturgists have been promoting.

A few links and oddities: The Vatican's own site has only the cover letter available in English at this writing. The text of both documents was actually leaked to Whispers in the Loggia and reported on there by Rocco Palmo, who charmingly says this about jumping the gun:

On a final note, in keeping with the firm policy of these pages and this narrator, let me state unequivocally that no embargoes were broken from this end in the obtaining of this text -- precisely because none was ever imposed.

...at least, not on me.

Tell that to Scooter Libby, I say. Actually, the point is idle, since the effective date of the motu proprio is September 14.

Note that this is not the only papal document with the title Summorum Pontificum. An Apostolic Letter was issued by Pius XI, endorsing the Spiritual Exercises of St. Ignatius Loyola. You can find it here, but it has nothing to do with Benedict's initiative.

* * *

As we noted above, Summorum Pontificum reverses the defaults on the use of the Tridentine Mass. Indeed, it goes further. What had been forbidden unless it was specifically permitted is now to be facilitated unless it is impossible. The Novus Ordo Mass, the "New Mass" that was promulgated after the Second Vatican Council, is to continue to be the "ordinary" form or use of the Roman Rite. The old Mass, known as the Tridentine Mass, is to be the "extraordinary" form or use, but "extraordinary" is not to mean "rare" or "disfavored."

The motu proprio makes provision for use of the old Mass by religious communities, and notes that any priest may say the old Mass "privately" with interested laity in attendance. The typical case which Benedict imagines is a parish where there is a "stable" group that wants the old Mass regularly. Apparently, if these people (no minimum number is given) ask the local pastor for a Latin Mass, he is supposed to accede to that request if it is at all possible. Where several Masses are said every Sunday, for instance, one might be in Latin, if a priest can be found who knows the use; or maybe one such Mass per month, if a Latinizing priest has to ride circuit. But suppose a pastor cannot or will not comply with such a request from members of the congregation?

Art. 7. Where some group of lay faithful, mentioned in art. 5§1 does not obtain what it requests from the pastor, it should inform the diocesan Bishop of the fact. The Bishop is earnestly requested to grant their desire. If he cannot provide for this kind of celebration, let the matter be referred to the Pontifical Commission Ecclesia Dei.

Art. 8. A Bishop who desires to make provision for requests of lay faithful of this kind, but is for various reasons prevented from doing so, may refer the matter to the Pontifical Commission ?Ecclesia Dei?, which should give him advice and help.

These articles suggest a great deal of oversight, more than is usual for the Catholic Church. And then there is this cordial to warm a liturgist's heart:

Art. 9, § 1. Likewise a pastor may, all things duly considered, grant permission to use the older ritual in administering the Sacraments of Baptism, Matrimony, Penance and the Anointing of the Sick, as the good of souls may suggest.

Why did Benedict take these steps? He speaks most about the schismatic Latin Mass groups, particularly the Society of Pius X. He notes that, in the past, the Church spun off new denominations because the hierarchy was not tactful and did not try to understand the protesters. We should note, though, that the actual Latin Mass schismatics are unlikely to be greatly mollified by Summorum Pontificum. The pope's documents insist that priests who use the Tridentine Mass also use the Novus Ordo when the occasion arises. That the priests of the Society of Pius X have refused to do.

The Latin Mass recusants make for interesting study, but I suspect that this interest is chiefly historical. As Benedict observes, the number of priests who could say a Tridentine Mass is limited, so Summorum Pontificum is not going to make an immediate difference in the way most parishes function. For the longer term, however, I would suggest otherwise. Consider this point that Benedict makes, almost as an afterthought:

Immediately after the Second Vatican Council it was presumed that requests for the use of the 1962 Missal would be limited to the older generation which had grown up with it, but in the meantime it has clearly been demonstrated that young persons too have discovered this liturgical form, felt its attraction and found in it a form of encounter with the Mystery of the Most Holy Eucharist, particularly suited to them. Thus the need has arisen for a clearer juridical regulation which had not been foreseen at the time of the 1988 Motu Proprio [from John Paul II, allowing the bishops to give permission to use the Tridentine Mass].

There are people for whom the Latin Mass is just a badge of identity, or a cover for a political agenda that does not bear close examination. This comment by J. Peter Nixon in yesterday's Commonweal Blog, however, describes the living impulse in the Latin revival:

As to what the “extraordinary form” can give to the “ordinary form,” it seems that its primary contribution will be “sacrality” rather than specific ritual forms...There are times when I think what many critics of contemporary liturgy want is not so much the 1962 rite but the 1962 rubrics.

The irony here is that we are talking about two Latin Masses. The "typical" version of the Novus Ordo is a Latin Mass from which translations were made into the world's vernaculars. Any priest at any time could use the Latin version, a version that easily accommodates the 1,500 years of liturgical music that is the chief reason so many people find the Latin liturgy worth saving. That was rarely done, however. The result, not all the time but too often, was the "sacrality" deficit that JP Nixon notes. In fact, Benedict makes the same point in his cover letter; the English even uses the term "sacrality." The pope expresses the hope that each use will be a good influence on the other:

For that matter, the two Forms of the usage of the Roman Rite can be mutually enriching: new Saints and some of the new Prefaces can and should be inserted in the old Missal.

It would have been better, perhaps, if the motu proprio had emphasized the esthetic improvement that old Mass could convey to the new. Just as it is possible to do the Novus Ordo movingly, so it is possible to say the old Mass, and particularly the Low Mass without music, with about as much edification for the congregation as turning a prayer wheel. If you think it's hard to find a priest who can say any kind of Latin Mass, just wait until you try to find a parochial "minister of music" who has a clue about Gregorian chant.

* * *

The Sacrality Deficit is not one of the points that liturgists of the US Conference of Catholic Bishops choose to address in their point-by-point comparison of the old and new Masses, though they do raise the possibility that the old Mass might be antisemitic. (The Tridentine service for Good Friday, not technically a "Mass," has prayers for the conversion of schismatics, heretics, Jews, and pagans: get over it.) We are also going to see a great deal of comical ecclesiastical politicking, some by bishops favoring Darwin Award liturgies and some by schismatics who will not take "yes" for an answer. There is also this: the Mass is a "killer application" for Latin, the sort of use that makes a technology ubiquitous. However, when Latin is studied these days, it is rarely the Italianate Latin of the Church, but a Classical reconstruction with a quite different pronunciation. The new Tridentine use could end up sounding quite different from the old, as it will be different in other ways.

These points, though, are just the sort of entertainment that history offers. The important trend will be the accelerating movement to overcome "the sacrality deficit," with all that means for the spirit and for culture. Benedict says that he is continuing the project that the Church began at the very beginning of the West:

Among Pontiffs who have displayed such care there excels the name of Saint Gregory the Great, who saw to the transmission to the new peoples of Europe both of the Catholic faith and of the treasures of worship and culture accumulated by the Romans in preceding centuries.

Documents and proclamations are only ripples on the deep currents of time. However, it is no fallacy to use them to mark an era, even when we know that era will not be plainly visible for some decades. For the purposes of the text books, we can say that the Second Religiousness of the West began on 7 - 7 - 7.

* * *

And while I am on the subject, here is an unpaid ad. Someday I will have to learn Flash.

[BE ad removed, as the Latin mass in question has long since ceased]

Copyright © 2007 by John J. Reilly

Support the Long View re-posting project by downloading Brave browser. With Both Hands is a verified Brave publisher, you can leave me a tip too!

Comments ()