The Long View: Flicker

More fun with Albigensians, this time in novel form.

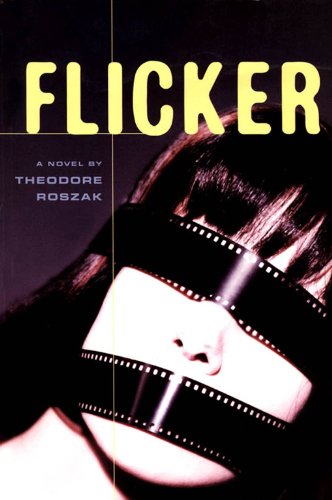

Flicker: A Novel

By Theodore Roszak

Summit Books, 1991

591 Pages, US$19.95

ISBN 10:155652577X

https://amzn.to/2YUEv6l

One pities Mr. Roszak his reader mail, because it’s going to sound like this:

At last the great conspiracy which has lain at the heart of Western history for the past 700 years has been publicly revealed. A single, hidden hand has been gradually guiding science, politics and the arts toward the planned sterilization of the planet in the year 2014. This hand is none other than the underground Albigensian Church.

Otherwise known as the Cathars, or “pure ones,” this sect is the linear descendant of the terrible Gnostic heresy founded by Simon the Magus, Christ’s contemporary and counterfeit. A thousand years later, they were in open control of southern France: the troubadours were their secret missionaries. The textbooks say that they were eradicated by the Albigensian Crusade of the first half of the thirteenth century, (The special courts called the Inquisition were invented to deal with them.)

However, these world-hating heretics were not destroyed. Rather, they spent the intervening centuries planning and infiltrating, until finally no major institution or system of thought in the West, indeed the world, is free of their influence. Of course, people who declare this danger openly are routinely branded insane or, when that will not serve, they simply “disappear.” Therefore Mr. Roszak has cleverly cloaked his revelations in the form of a novel, purporting to be the memoirs of a UCLA film school professor. Those who have discovered the ghastly truth for themselves, however, will see what he is really up to.

Well, maybe. What Mr. Roszak really seems to have done is to have critiqued the antinaturalist streak in modern culture with rare wit and persuasiveness. In point of fact, while the business about Cathars, Templars and Albigensians will prove to be enormously entertaining to connoisseurs of conspiracy theories, the bulk of the book is a rousing satire of film criticism, academic and otherwise. He pulls this off by describing how his hero, a young and slightly gullible film historian, starts his academic career about 1960 viewing film noir masterpieces in a grimy repertory house, only to end up writing reviews (just before the Albigensians get him) of “serious” movies with titles like The Lonesome Lovesong of the Sad Sewer Babies.

The author has argued in some of his earlier works (he is chiefly known for his account of the 1960s, The Making of a Counter-culture), that there is in fact a “Gnostic” element running throughout Western history. This is a tendency to despise the physical world as we perceive it. In the work of scientists, this takes the form of the search for disembodied abstractions behind particular phenomena. On the cultural level, it shows up as a loathing and contempt for ordinary human beings, for ordinary life, for the system of the world as it stands. Though he nowhere says so, Roszak seems to be suggesting that the very notion of the avant garde, the definition of artistic merit as “the shock of the new,” is founded on a hatred for life itself.

We learn about this through the reminiscences of a man who began attending art films in high school so as to see as much exposed female skin as possible. What first brings the hero of the book into contact with the Great Conspiracy, however, is his study of a director from Weimar Germany who immigrated to Hollywood in the 1920s. Once there, this director’s career rapidly degenerated. Finally, he could find work only in horror flicks filled with vampires and mummies.

The young scholar eventually realizes that these B movies are more affecting than they have any right to be. He soon discovers that they have ingenious subliminal effects, movies within movies, designed to make violence seem attractive and normal sex disgusting. (If you’ve ever had any questions about Tantric sex, by the way, this book will answer them, I think.) The clincher is the discovery that these subliminal messages are a form of conditioning by the eccentric religious organization which raised and educated the director.

The Gnostics of history, and apparently also the real Cathars, were Dualists. They held that a good god and an evil god were at war in the universe. The world of history was the domain of the evil god, who keeps the souls of men entrapped and deluded in matter through the horror of organic life. It is the hope of the Cathars (in the book) to end procreation, and indeed biological life.

One can, of course, suggest that a spiritual mood can be reproduced at different times and different places without being transmitted through an organization or a tradition. For instance, the chief modern historian of Gnosticism, Hans Jonas, has suggested that the more manic depressive forms of Existentialism manifest a type of cosmic despair that is strongly reminiscent of Gnosticism but without being derived from it. Roszak’s more modest proposal is that the relentless increase of violence, scatology, and pure horror in the popular media, particularly film, represents a cultural atmosphere that the Cathars would have cultivated if they were alive today.

It was no small accomplishment on Roszak’s part to put this grim thesis across with considerable hilarity. Though his universal conspiracy will probably get more attention than it deserves (it certainly has in this review), it is very good for its class. It is certainly much better than that scruffy crew Umberto Eco got together for Foucault’s Pendulum, which had much the same class of conspiratorial characters. There are lots of nice touches his research obviously suggested, such as the fact that the Cathar bigwigs all bear the names of obscure Gnostics heretics (Father Marcion, Brother Valentius, etc.) from the early Christian era. I might also note that the god Odin, who appears briefly in the guise of a UCLA professor of medieval studies, makes rather a muddle of the relationship between the Cathars and the Templars, but even the muddle is in character.

Of course, any attempt to recite the cultural history of the last thirty years is bound to have some unintended glitches; the one rock group he discusses in detail, called The Extinction Now Boys’ Choir, can’t seem to make up its mind whether it’s early punk or late speed metal. However, this is nitpicking.

This may not be just any book. For decades now, anyone confronted with a film that shocked or reeked of despair would be inclined to give it the benefit of the doubt. Isn’t the breaking down of inhibitions what art is supposed to be about? Roszak suggests, by implication, that it doesn’t have to be.

This review originally appeared in the January 1992 issue of Fidelity.

Copyright © 2007 by John J. Reilly

Support the Long View re-posting project by downloading Brave browser. With Both Hands is a verified Brave publisher, you can leave me a tip too!

Comments ()