The Great Year Book Review

The Great Year By Nicholas Campion Penguin Books (March 1, 1995)

Damian's endorsement of the Great Year

By Nicholas Campion

Penguin Arkana, 1994

696 Pages, US$14.95

ISBN 9780140192964

I picked this book up on the advice of Damian Thompson, Catholic gadfly and Internet rabble-rouser. It has taken me a while to get around to it, but this is a propitious time.

This book is by turns fascinating and maddening. Campion's survey of the development of astrology in the Middle East is superb. I don't think I ever truly appreciated the way in which astrology was the political science of its day: an attempt to guide acts of state using the best knowledge available. On the other hand, Campion's use of primary sources seems fanciful, at best. In most cases, when I am familiar with the work cited, I don't agree with his interpretation. It is also far too long. I might have been more inclined to entertain Campion's theories if he didn't repeat himself quite so often, at such length.

The grandest of Campion's theories is that you can trace a common thread from Sumer in 3000 B.C. to contemporary Christian millenarians. I think this theory has quite a bit of truth in it, despite Campion's penchant for making lazy associations between any two things that share a superficial similarity. The grand sweep of the theory is this: the Babylonians inherited the political astrology of the Sumerians, which was part of a broader tradition common to the Near East. Key elements of that political astrology, along with foundational myths, were borrowed by the Jews. Christianity then merged Jewish apocalypticism with Greek philosophy [also heir to common astrological traditions], and then went on to dominate the thought of Europe. That seems reasonable, so broadly stated. It is the details that keep tripping me up. Let's delve into those details a bit.

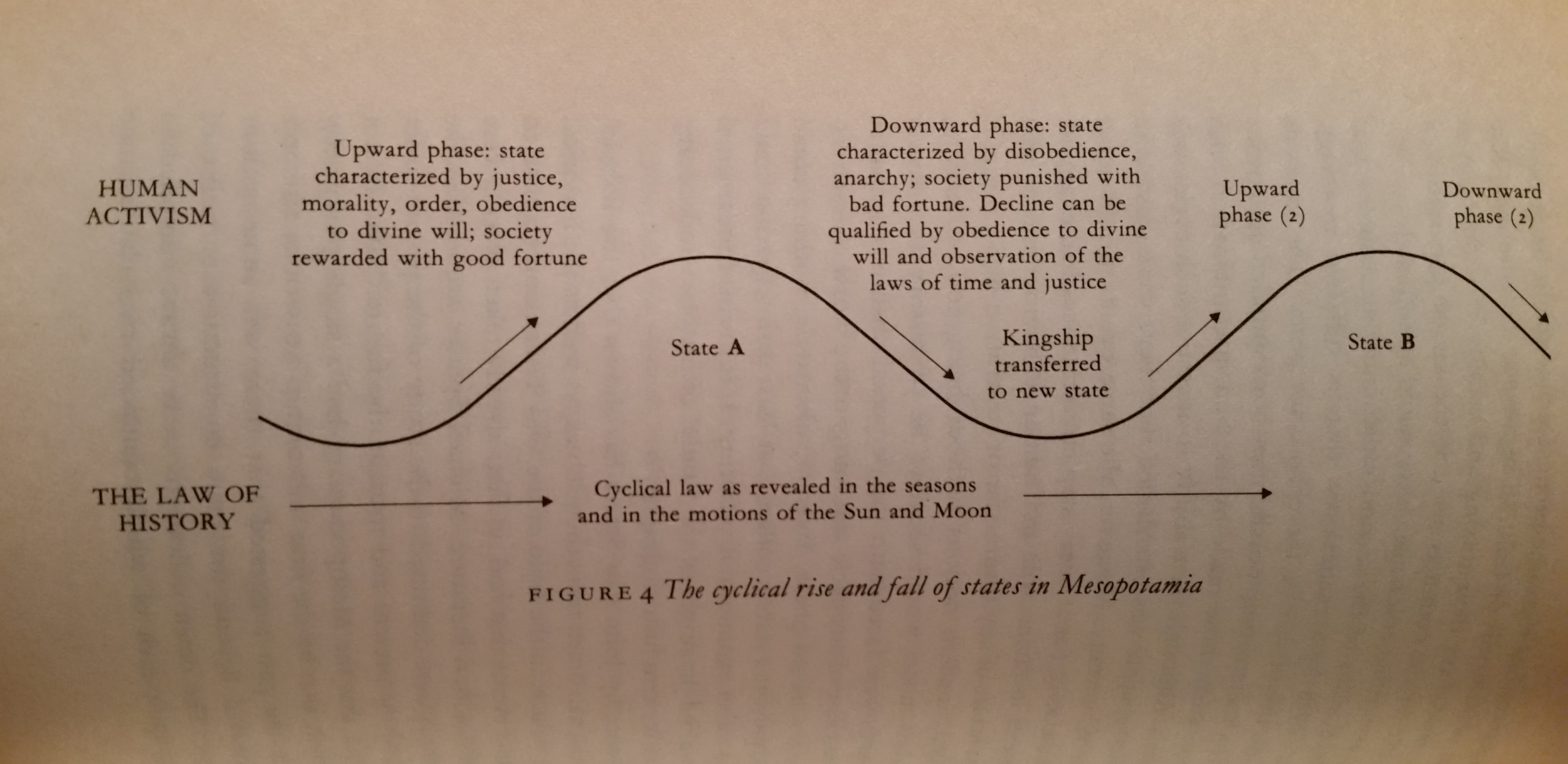

I found the initial chapters on Sumer, Babylon, and Egypt the most interesting. I also know very little about the Bronze Age history of these cultures, so perhaps that explains why this bit was more fun to read. The start of astrology was omen divination, driven by "a belief that events that occurred at the same time are connected for that very reason," [Campion p. 51] along with the observations of the periodicity of the day and the year. Campion divides divination into two fundamental types: operational and observational. Operational divination actively sought an answer from the gods, whereas observational divination simply took note of the prevailing conditions.

This started to get very sophisticated by the eighth century B.C., which is when we start to see very detailed astronomical records, and something like a theory of history. How those worked together was that if you could predict the positions of the planets relative to the constellations, then you could expect to know the timing of the next cycle based on the last cycle, and adjust your behavior accordingly.

Campion p. 56

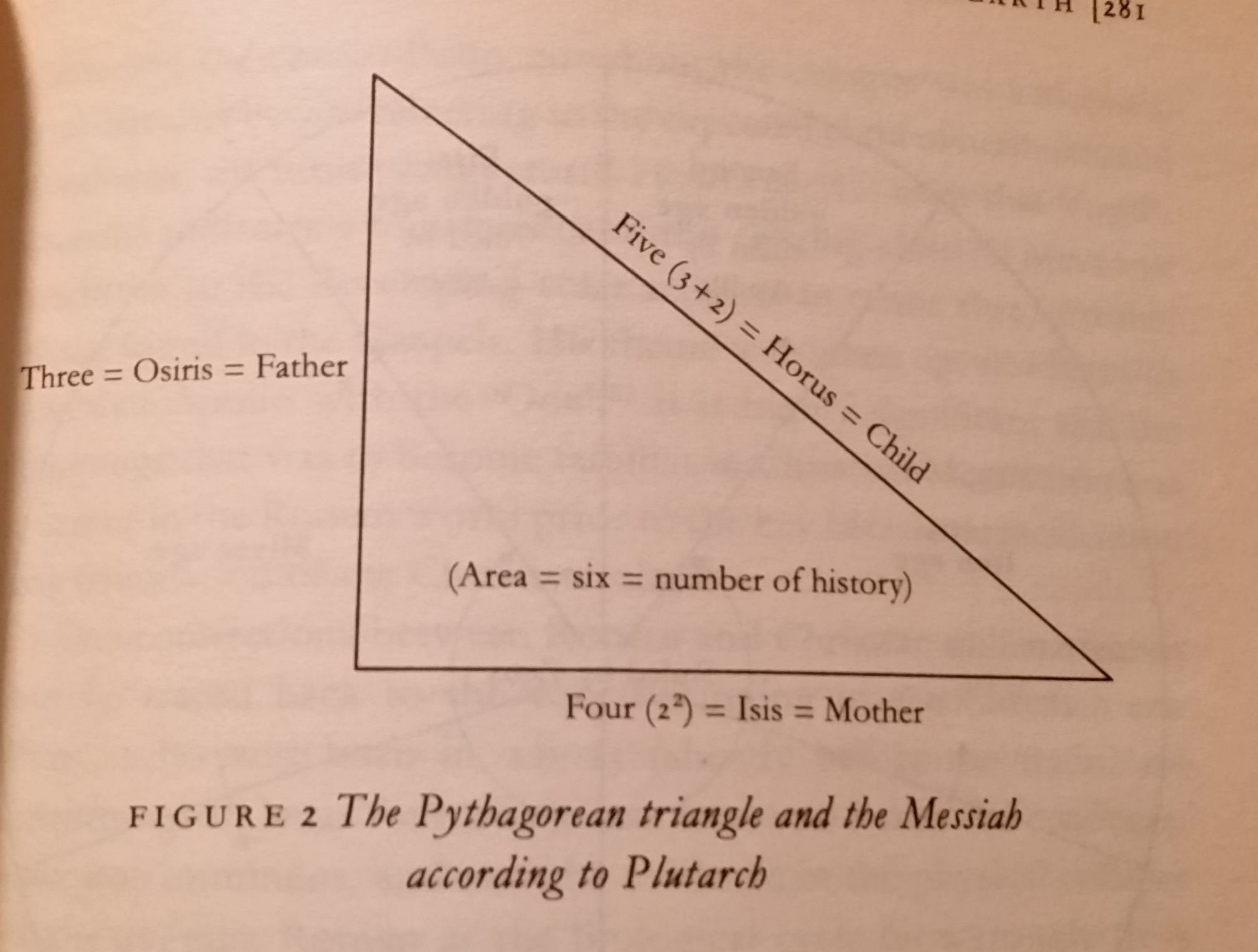

Chapters 3-7 contain an explanation of the common tradition of Near Eastern numerology. While I generally enjoyed the first third of the book, this is my favorite section. When I was considering becoming a Catholic, I was fascinated that numerology used to be a significant part of Christian thought, and Greek philosophy as well, but that in the modern West it is limited to the kookier types. Campion's presentation of the idea helped me see it as a 5th century Pythagorean might have, as an expression of the beauty and perfection of the universe. That alone was worth it.

Campion p. 281

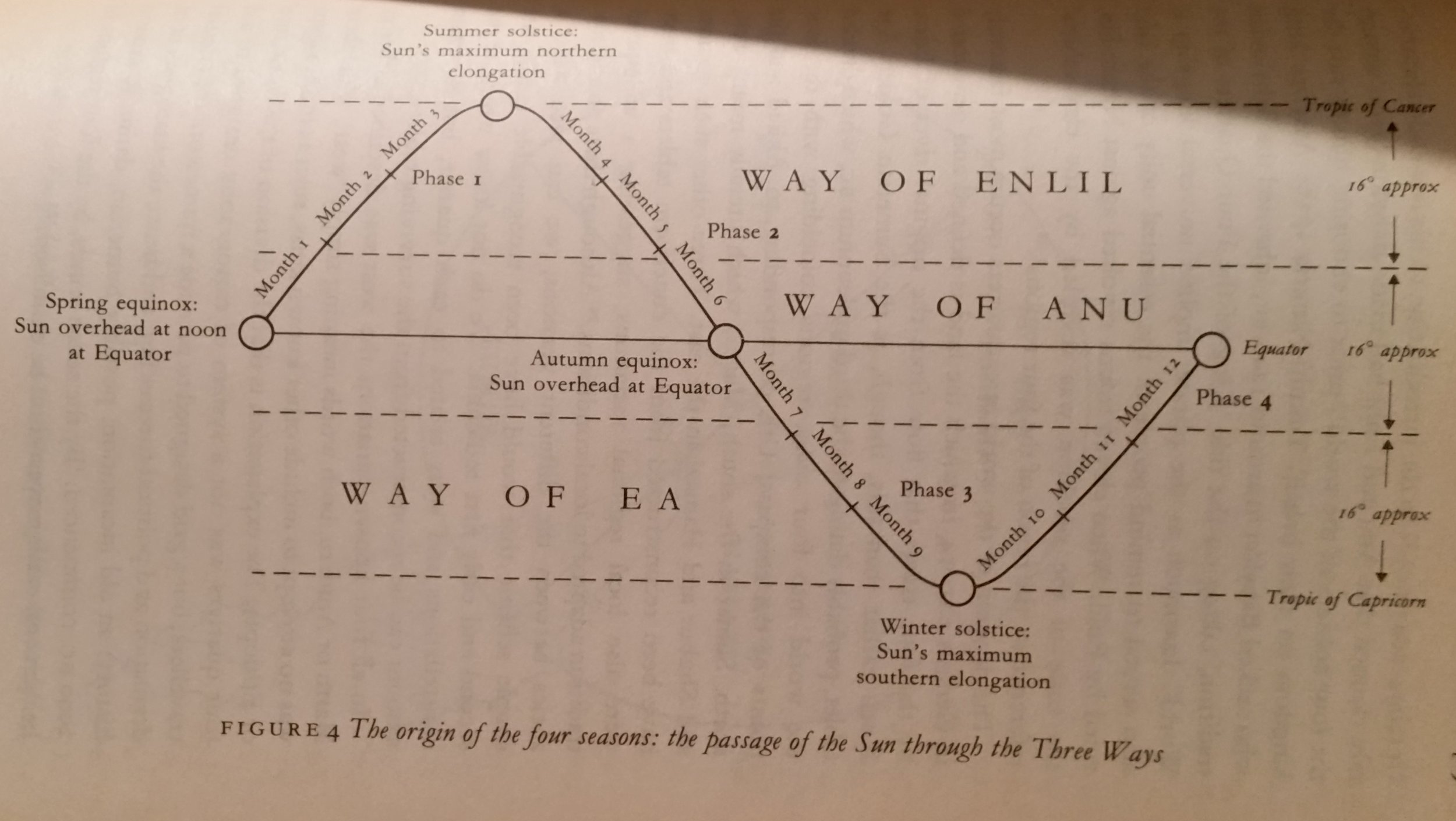

On one level, the symbolism of numbers was purely conventional, insofar as the symbols for the gods in Assyria were simply repurposed cuneiform numerals. On another level, these numbers seemed to represent fundamental truths about the world. For example, 3, 4, 7, and 12 were numbers of great meaning in this Near Eastern numerological tradition. Three had a variety of meanings, including the fundamental familial relationship of father, mother, and child, but the meaning that tied it all together was the way the motion of the rising and setting sun came to be identified with three regions. As the seasons progress, the sun moves to the north, returns to the center, passes the center to the south, and returns to the center. There are three regions, but four seasons, linking 3 and 4. In terms of geography, the three regions are the Equator, the Tropic of Cancer to the North, and the Tropic of Capricorn to the South.

Campion p. 89

Twelve comes in both because it is three times four, and because there are approximately twelve lunar months in a solar year. This all then gets tied in to astrology because each month was marked off by a constellation in the Zodiac. The signs of the Zodiac were used in the Assyrian political astrology because that was a convenient way to remember when things happened in the past, and could be expected to happen again in the future.

Seven is three plus four, but other than that Campion has no ready explanation for its significance. There is the legend of the Seven Sages, a legend that is common to Babylon, Greece, Rome, and China, at the very least, which claims that civilization arose from seven wise men, or fish men, or something.

We have relatively better examples of the writings of the classical Greeks and Romans, where these ideas were polished to perfection. Campion gives examples of this from a number of well-known authors of the period, including Pythagoras, Plato, Aristotle, and Plutarch. However, this is where the book started to come off the rails for me, since I am reasonably familiar with most of Plato and Aristotle's major works.

For example, at the beginning of chapter 7 we have this section:

Campion p 187

Let's look at that footnote 2:

Campion p 567

And the referenced work of Aristotle:

[1072a] [1] Again, Plato at least cannot even explain what it is that he sometimes thinks to be the source of motion, i.e., that which moves itself; for according to him the soul is posterior to motion and coeval with the sensible universe. Now to suppose that potentiality is prior to actuality is in one sense right and in another wrong; we have explained the distinction.But that actuality is prior is testified by Anaxagoras (since mind is actuality), and by Empedocles with his theory of Love and Strife, and by those who hold that motion is eternal, e.g. Leucippus.

Therefore Chaos or Night did not endure for an unlimited time, but the same things have always existed, either passing through a cycle or in accordance with some other principle—that is, if actuality is prior to potentiality. Now if there is a regular cycle, there must be something which remains always active in the same way; but if there is to be generation and destruction, there must be something else which is always active in two different ways. Therefore this must be active in one way independently, and in the other in virtue of something else, i.e. either of some third active principle or of the first.It must, then, be in virtue of the first; for this is in turn the cause both of the third and of the second. Therefore the first is preferable, since it was the cause of perpetual regular motion, and something else was the cause of variety; and obviously both together make up the cause of perpetual variety. Now this is just what actually characterizes motions; therefore why need we seek any further principles?

Since (a) this is a possible explanation, and (b) if it is not true, we shall have to regard everything as coming from "Night" and "all things together" and "not-being," [20] these difficulties may be considered to be solved. There is something which is eternally moved with an unceasing motion, and that circular motion. This is evident not merely in theory, but in fact. Therefore the "ultimate heaven" must be eternal. Then there is also something which moves it. And since that which is moved while it moves is intermediate, there is something which moves without being moved; something eternal which is both substance and actuality.

Now it moves in the following manner. The object of desire and the object of thought move without being moved. The primary objects of desire and thought are the same. For it is the apparent good that is the object of appetite, and the real good that is the object of the rational will. Desire is the result of opinion rather than opinion that of desire; it is the act of thinking that is the starting-point.Now thought is moved by the intelligible, and one of the series of contraries is essentially intelligible. In this series substance stands first, and of substance that which is simple and exists actually. (The one and the simple are not the same; for one signifies a measure, whereas "simple" means that the subject itself is in a certain state.)But the Good, and that which is in itself desirable, are also in the same series;

The concepts Campion points to are referenced here, but they are rather orthogonal to the point Aristotle is making, which is what a First Cause, or an Unmoved Mover would have to be like.

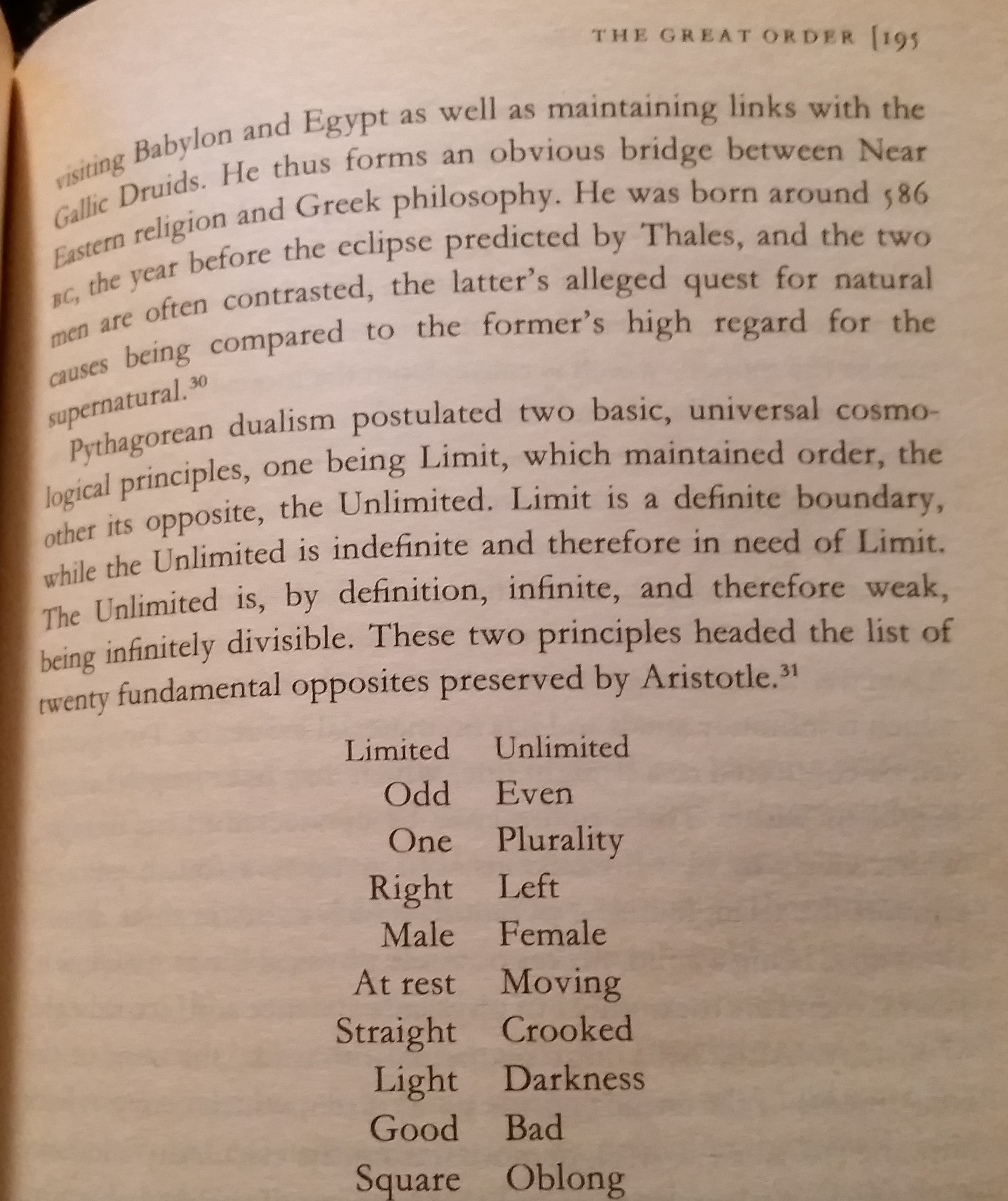

And another, this list from the Metaphysics:

Campion p 195

Which is preserved by Aristotle, but mostly as something he wants to expand upon and partly argue against. There is a very narrow sense in which these footnotes are defensible, but not in the way they are used here. Which got me to thinking: if Campion does this where I know the sources this well, what is he doing where I don't?

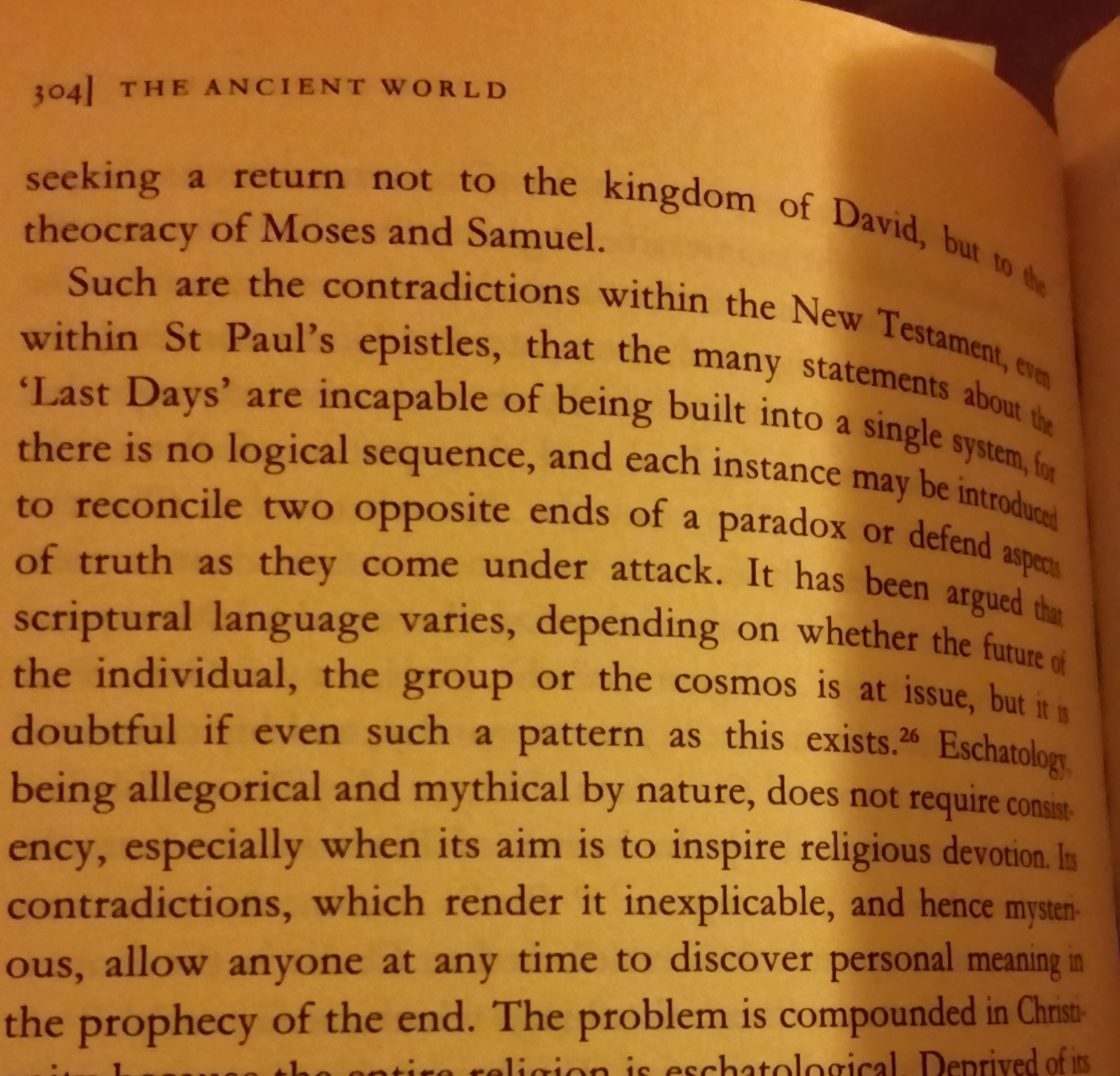

I also found Campion's village atheist shtick grating. I have no idea what Campion's beliefs are, other than "astrology", but his style follows that of notable English freethinkers in insisting upon scoffing at things not actually found outside of folk religion, for example this claim that St. Paul's eschatology cannot possibly be systematized. Or his odd claim that a Babylonian foundation for the Jewish flood myth completely undermines Judaism, which depends upon everything in the Torah being 100% autochthonous.

Campion 304

At the end, I think I can agree with Thompson's endorsement of The Great Year. Cyclical theories of history are currently out of fashion, which is quite different than being false. Honest looks at millennarian movements and their influence on history are also rare. I think you can look at this same subject without the theatrical snipes at religion and with higher standards of proof, and end up with a pretty similar place. Given those caveats, I think it is worth delving into these negelected subjects.

The Great Year: Astrology, Millenarianism, and History in the Western Tradition (Arkana) by Nicholas Campion (1995-03-01) By Nicholas Campion

Comments ()