The Pastel City by M. John Harrison

The Pastel City by M. John Harrison is a tightly written tale of defeat and triumph, duty and revenge, all in 144 melancholy pages. It is vastly different than the kind of fantasy book often written now. More happens in this slim volume than in trilogies of contemporary works. And this is only the first one in the Viriconium sequence.

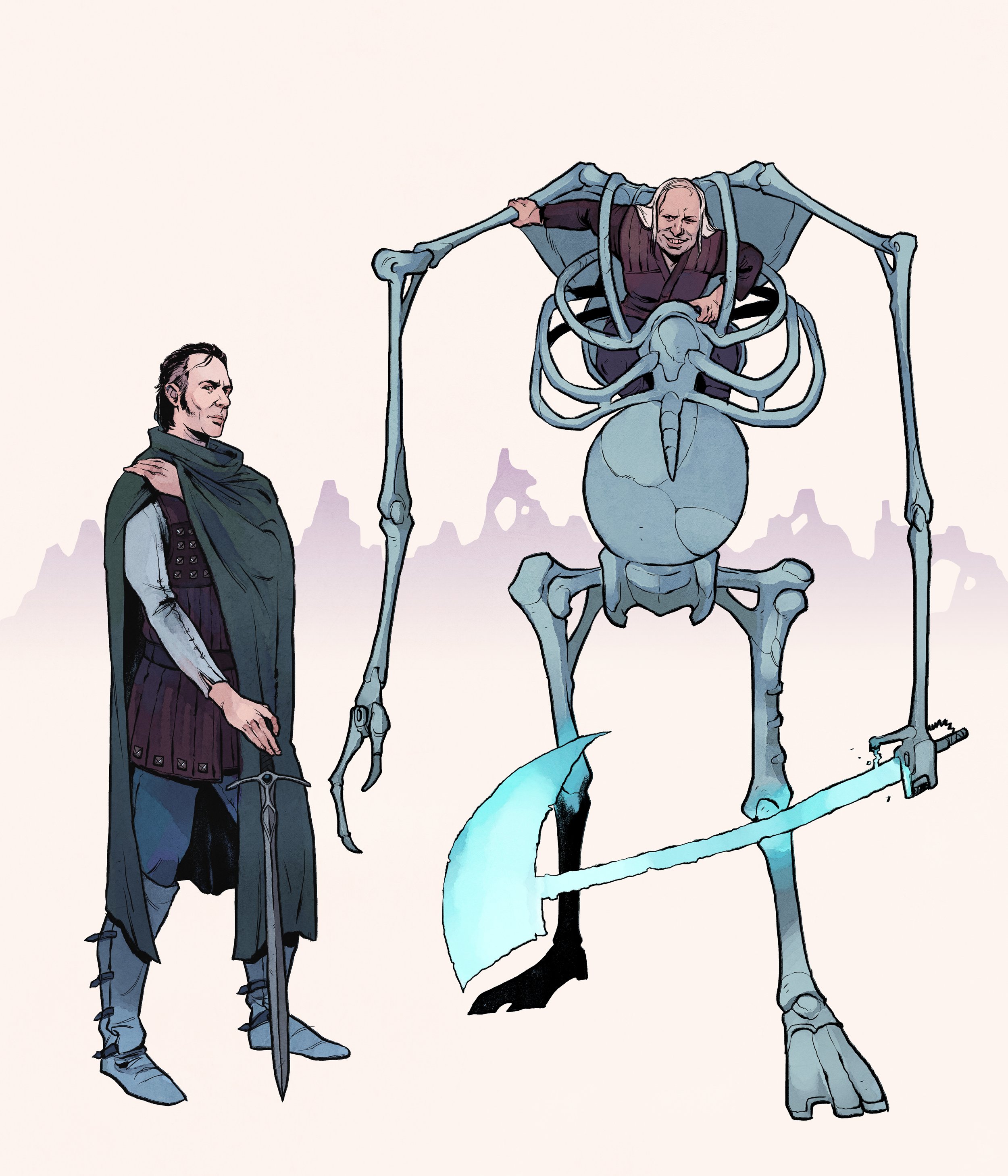

It was this image of two men, one shrunken and leering, the other pensive but raptor-like, that made me go pick up this book. Without ever knowing who Tomb the Dwarf or tegeus-Cromis were, this image captured something essential about these characters that made me want to know more.

A part of the magic of Harrison’s style is there is both more and less than most readers probably expect in the exposition. There is great deal of compact, allusive language, a world painted in deft thrusts like the play of an epee or a rapier in the hands of a master.

Some seventeen notable empires rose in the Middle Period of the Earth. These were the Afternoon Cultures. All but one are unimportant to this narrative, and there is little need to speak of them save to say that none of them lasted for less than a millennium, none for more than ten; that each extracted such secrets and obtained such comforts as its nature (and the nature of the universe) enabled it to find; and that each fell back from the universe in confusion, dwindled, and died. The last of them left its name written in the stars, but no one who came later could read it. More important, perhaps, it built enduringly despite its failing strength—leaving certain technologies that, for good or ill, retained their properties of operation for well over over a thousand years. And more important still, it was the last of the Afternoon Cultures, and was followed by Evening, and by Viriconium.

What there isn’t is the kind of world-building that lends itself to a wiki, or a detailed timeline or map. Harrison delights in artful ambiguity and layered references. His places, the Pastel Towers, the Rust Desert, the Metal Bog, evoke emotional responses in with their direct and literal names. Some fool on Wikipedia was so bold as to claim this as a “subversion” of Tolkien, but then was so witless as to link to an essay by Harrison “What It Might Be Like to Live in Viriconium” that says the opposite.

I’m just going to quote Harrison directly:

The great modern fantasies were written out of religious, philosophical and psychological landscapes. They were sermons. They were metaphors. They were rhetoric. They were books, which means that the one thing they actually weren’t was countries with people in them.

The commercial fantasy that has replaced them is often based on a mistaken attempt to literalise someone else’s metaphor, or realise someone else’s rhetorical imagery. For instance, the moment you begin to ask (or rather to answer) questions like, “Yes, but what did Sauron look like?”; or, “Just how might an Orc regiment organise itself?”; the moment you concern yourself with the economic geography of pseudo-feudal societies, with the real way to use swords, with the politics of courts, you have diluted the poetic power of Tolkien’s images. You have brought them under control. You have tamed, colonised and put your own cultural mark on them.

It is clear that Harrison’s real target was the soulless Tolkien clones that took over fantasy in the wake of the monumental success of the Lord of the Rings. Harrison wanted to recapture the power and magic of Middle-Earth, and he decided the best way to do that was to set out in an entirely different direction.

The result is elegiac, haunting and wistful in the twilight world of Viriconium, graveyard of mankind’s hopes and dreams. This is an adventure, but it is played in a minor key. The days of glory are long past, and now what is left is only a memory of greater things.

I picked up a copy of the paperback from Abebooks, and you can also find an omnibus edition of all the Viriconium stories at Amazon.

Comments ()