Why Christians Should Read Adventure Fiction

I think the obvious answer to the question, “should Christians read adventure fiction?”, is “Yes”, but since I see a surprising amount of discomfort around the topic, I thought I would delve into it more deeply. I can posit at least three reasons that I will explore at length:

- Adventure is one of the foundational types of literature.

- Adventure fiction provides escapist entertainment.

- Adventure fiction is a tool for shaping healthy masculinity.

I take it as foundational that Christians want to engage with culture, to enjoy good stories, and to help men live their vocations, whatever they may be. I am well aware that not everyone does want these things, but that conversation isn’t really about stories at all.

Adventure fiction

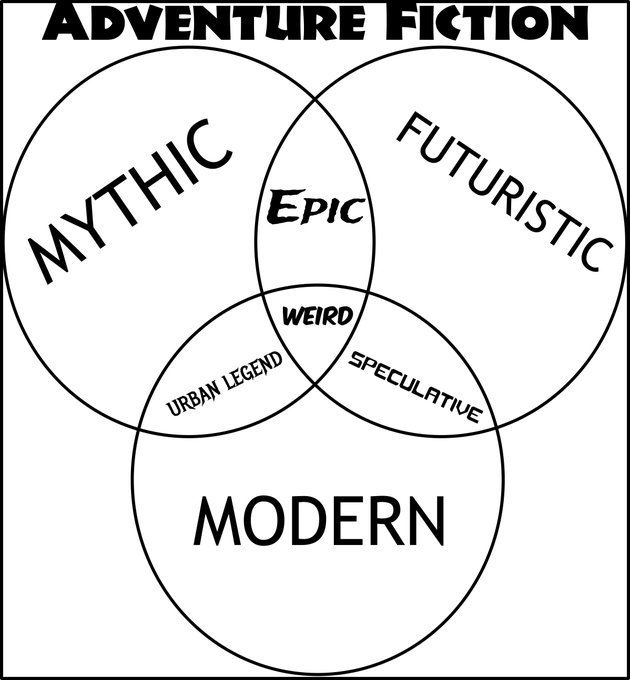

When I say that I think Christians should read adventure fiction, it is important to define terms, as “adventure” is a pretty broad term, and it is likely to be interpreted in a variety of senses. I mean stories that evoke a sense of wonder. The older term, now hopelessly confusing, is a romance, a sequence of marvelous adventures. Romance, along with tragedy, comedy, and irony, is one of the four fundamental types of stories you can tell.

JD Cowan explains the essence of wonder fiction:

Wonder is a trait from adventure fiction and its subgenres fantasy and horror. It is the adventure of exploring new lands, peoples, and possibilities.

Cowan expands on this by quoting Sam J. Lundwall in Fandom: An Illustrated History:

"Its strong connections with the Medieval chansons de geste and other tales of chivalry with their unbearable noble heroes, incredible, constantly swooning ladies and unbelievable villains, gives the genre life and gusto and guarantees new, staggering thrills on every page. It is very dramatic, alternating between the pathetic and the grotesque and characterized by mighty heroics, swords, blood and hideous slithering things in the darkness of convenient crypts."

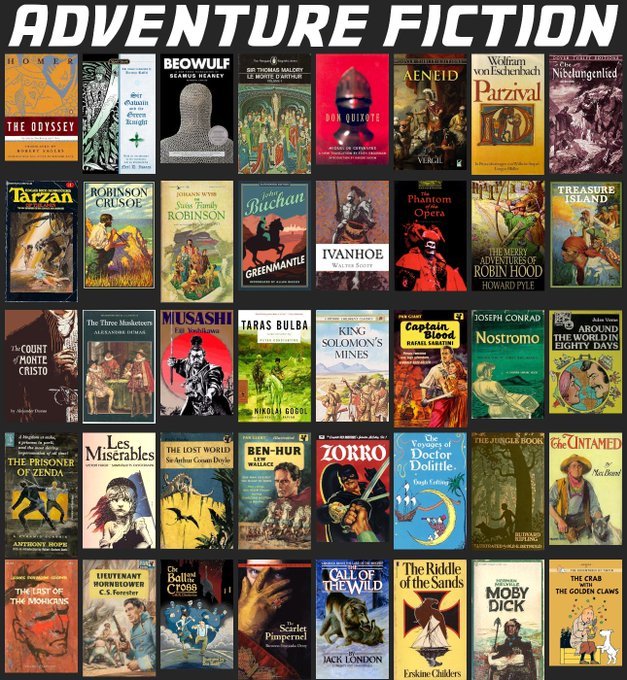

Many of the oldest stories we know of, The Odyssey or the Epic of Gilgamesh for example, are adventures. Adventure has been very popular for a very long time, and this form contains many great works of literature that you need to read to be part of the great conversation. I don’t think that is a requirement for everyone, but I started with it because I suspect that a great many people who look askance at adventure as “low quality” are making a mental reservation for important classic works.

But to do this forms a lacunae in your understanding of the world. Contemporary conventions of literary realism and plausibly reflecting the world as it is can inadvertently bind you to the conventions of our culture and our time. Literary fiction has pretensions of critiquing the shortcomings of our civilization, but in reality it is mostly a reflection of its worst aspects. By way of contrast, consider what Thomas Bertonneau said about the works of Edgar Rice Burroughs, an immensely popular author who if he is remembered at all, is considered to have written works that “dealt with their themes in a childish way”:

The Burroughsian Female and the Modern Male. I detect in these prefatory complaints and apologies the figural stand-in for a deeper anxiety that goes unspoken partly, I suppose, out of fear that speaking it will, to invoke the metaphor, spill the beans about a severe limitation in the contemporary literary sensibility, even, or perhaps especially, where it concerns popular narrative. Burroughs did not quite invent, but he refined and codified a robust popular masculine narrative, which, while celebrating heroic character, also promulgated the values of literate knowledge and philosophic inquiry. Burroughsian narrative also provides the locus for a non-systematic but incisive critique of the standing culture, as it became increasingly emasculated, regulated, and anti-intellectual in the middle decades of the Twentieth Century. This same masculine narrative entails, finally, a conception of the feminine that elevates the woman to the same level as the man and that – in such characters as Dian of the Pellucidar novels or Dejah Thoris of the Barsoom novels – figures forth a female type who corresponds neither to the desperate housewife, the overdressed prom-date, the middle-level careerist office-manager, nor the frowning ideological feminist-professor, but who exceeds all these by leaping bounds in her realized humanity and in so doing suggests the insipidity of the contrasting personality types.

In addition to apologizing for Burroughs in various ways, the preface-writers for the Bison editions emphasize the “escapist” quality of Burroughsian fantasy. Without pushing the paradox too far, I would say that A Princess of Mars, Lost on Venus, Pellucidar, and Beyond Thirty respond healthily to the increasingly unreal character of life itself in the emerging, submissive consumer-society of the Mid-Twentieth Century and beyond. One judges escapism by measuring it against that, from which it would escape. In addition, while Burroughsian narrative is unapologetically escapist, it is at the same time satiric and critical. Burroughs knows reality quite well; he understands it and he knows that his readership understands it. The social critique belongs to the shared experience of the story – the communion between writer and audience.

I believe that if you look at the way literature and culture has moved in the years since the Great War, you can detect what C. S. Lewis lampooned as “men without chests”, a marked lack of fierce passion directed to the true and the good. The point of art, especially popular art, is to form the emotions. The contempt and disregard directed toward one of the four pillars of literature has produced a lack of just sentiments, emotions rightly ordered to reality. Wonder fiction is perhaps best suited to this task. Read adventure, it is good for you.

Foundational works of adventure fiction

However, adventure fiction also contains many works that are simply escapist entertainment, low art in the best sense of the word. But again, I think it is important to define terms. Low art and popular entertainment are often used as pejoratives, but they should not be.

Let’s look at what Cowan had to say about low art in his book Pulp Mindset:

Low art deals with visceral and tangible goals and stakes, while high art deals with ephemeral and heady concepts.

…

If you’re reading a book by Dostoevsky or Flannery O’Connor, you are not there to be greeted with fast-paced stories of heroes shooting villains and rescuing space princesses. This sort of fiction exists for an entirely different reason than the pulps. People pick up an adventure book for the thrill of it all, not to examine their souls and learn more about why we are here and where we are going. High art is made to dwell in more complex spaces, while low art deals in excitement. You read high art to understand higher things, not to be be pulled into a globe-trotting yarn.

What low art exists for is this escapism, and it does this with its greatest weapon: action.

So I think this raises the question: why is escapism good? This is another term used with a negative connation, but I want to challenge that usage.

Peter Lawler wrote this at Mind & Spirit about Percy Walker’s book Lost in the Cosmos:

"From Percy’s view, our bookstores are mostly filled with two kinds of books—self-help books and diverting or entertaining books about scandal-ridden law firms or extraterrestrials or VAMPIRES or a bunch of sexually obsessive shades of grey. Diversions, of course, get your mind off yourself, relieve your stress, help out in alleviating your fears, your anxieties, your boredom. According to Blaise Pascal, most of our lives are diversions, escapes from what we really know, evidence of our misery without God. According to Percy, most of our lives these days are diversions that become progressively more disappointing. The pursuit of happiness has become the pursuit of diversion in the midst of prosperity. And one problem among many about living in our highly self-conscious time is that diversions we know are merely diversions are boring or only very weak and evaporating antidotes to despair. That’s why Percy knew people visiting museums are mostly ineffectively fending off despondency. That’s also why highly educated bourgeois Americans today try so hard and fail so miserably in being bohemians too."

As Cowan says in his commentary on escapism, we feel lost because we are lost. No Christian should be surprised that we do not truly feel at home in this world. But that doesn’t quite get at why escapist entertainment is good. Adventure, wonder fiction in the sense that I am using the term, always points at something beyond this world even while it entertains. That is the transcendence that makes the best fiction more than the mere pursuit of diversion.

The larger-than-life heroics that are a standard feature of adventure can be a signpost pointing to greater things. But we should never confuse good stories tor the Good News. Fiction cannot save you, although I do think it can help you on the journey.

Which is where we transition into the final point, that adventure fiction can help foster healthy masculinity. One of the ways it can do this is by illustrating the archetypes that lay behind masculinity, giving us something to aspire to. Wonder fiction, or adventure, is stereotypically male, although not quite as limited in its appeal to women as the female-dominated relationship-oriented genre we now call romance is to men.

However, not everything that can be plausibly called “adventure” is actually going to be helpful in fostering healthy masculinity. And I suspect the accurate perception that some adventure fiction is like this prevents people from seeing the value in the rest.

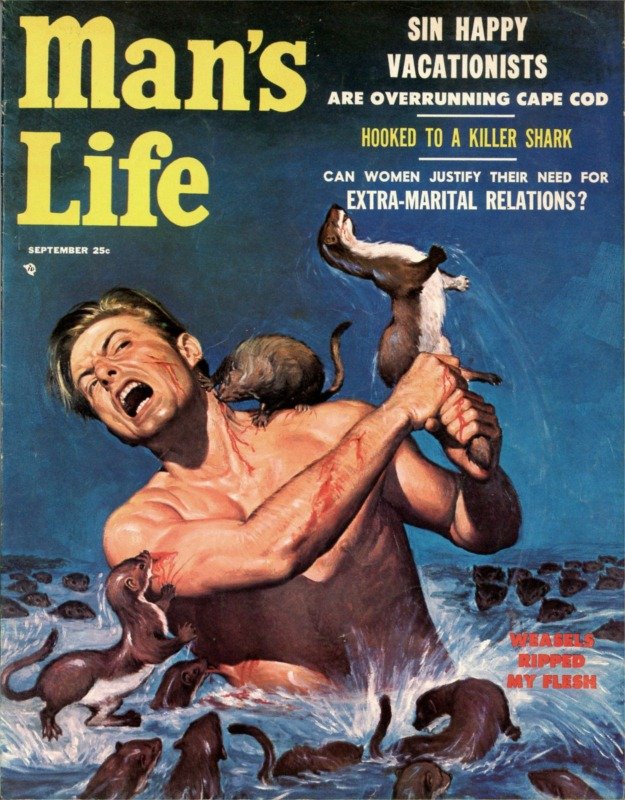

The pre-eminent example of less-than-aspirational fiction is the “Weasels ripped my flesh” kind of men’s “adventure” magazine. But why not? It has adventure in the title after all. I will admit to a lack of experience with the kind of stories you can actually find in these magazines. I would not be surprised if there were some hidden gems in there. The best I can do is judge a book by its cover. And the covers do promise action and adventure, but also titillation.

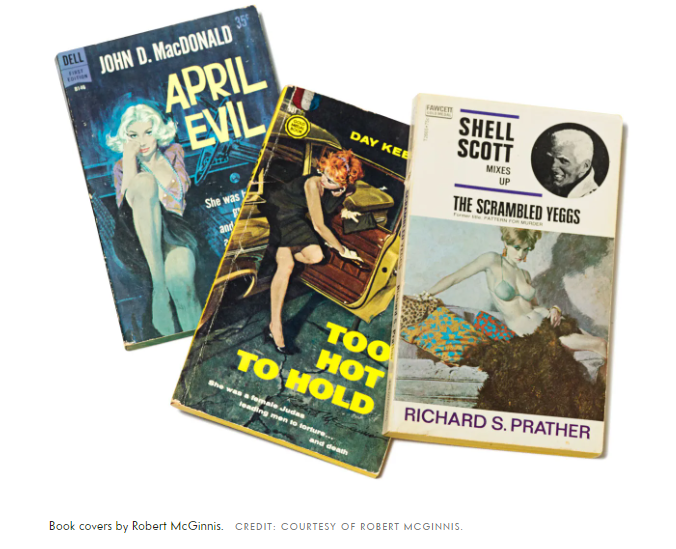

And as women’s romances run the gamut from Jane Austen to mommy porn, adventure fiction marketed to men spans a range from Robert Louis Stevenson to the kind of paperback with an egg tempera cover by Robert McGinnis.

At best, such things may be harmless. But in a world still recovering from the collective madness unleashed by the sexual revolution, I advise caution in consuming too much fiction that appeals to prurience.

If you accept that the purpose of art is to form the emotions, and that popular adventure stories engage with the emotions in a particularly direct way, then it makes sense to seek out stories that embody the best a man can be. The thing I find most fascinating about the best works of adventure is that they can be crafted as thrilling works of low art, yet are as incisive about the human condition as any literary novel. In fact, some parts of human experience are far better represented by wonder stories than by the contemporary conventions of the realistic novel. Particularly because the real world is far weirder than the conventions of the literary novel can allow.

Triumph of The Cross fresco (detail), 1585, Sala di Costantino, Vatican Palace.

Let us turn to the late Bertonneau again, in this essay on why Robert E. Howard’s Conan is a paracletic hero

Howard’s story appears in the same number of Weird Tales as C. L. Moore’s “Black Thirst,” one of her Northwest Smith sagas, and Clark Ashton Smith’s “Death of Malygris,” an item in his Poseidonia cycle. Howard resembles Moore and Smith in achieving a signature literary style that betokens a profound literary basis, especially in the traditions of myth and epic, and an intuitive grasp not only of metaphysics, that science of the invisible, but of the deep structure of morality. Twenty years ago, in an article for the journal Anthropoetics entitled Monstrous Theologies, an obscure scholar of genre fiction classified Moore’s Northwest Smith as a “Paracletic Hero.” The author had discerned in reading Moore’s story-cycle the recurrent pattern wherein Smith acts to free an afflicted community from the tyranny of a sacrificial order. The term Paracletic derives from the Greek name for the Third Person of the Trinity, who functions, in one of his roles, to bear witness against the injustice of scapegoating, a human propensity that manifests itself as ritual – the immemorial but hidden reign of which Christian revelation brings to light. Smith’s stories likewise expose the gruesome vanity of sacrifice, but without the explicit moral framework of the Moore’s narrative and lacking a heroic protagonist. Sacrifice furnishes a recurring theme in the Conan sequence to the degree that Conan also qualifies, if not quite so fully as Northwest Smith, as a Paracletic Hero. Human sacrifice inspires Conan with revulsion. Conan’s deity, Mitra, whom he regularly invokes, figures in a religion that explicitly rejects human sacrifice and in so doing differentiates itself from the other cults of Howard’s Hyborian Age.

Conan is in fact the worst barbarian ever, because the character is not intended to be an anthropologically accurate portrait, but rather an archetype brought to life in a way that both satisfied the deep structure of myth and legend, and was also entertaining to the ordinary people who paid to read these stories.

There is abundant anecdote that Burroughs and Howard and the rest were inspiring to their readers. That in some small way, these stories were not just a way of passing the time, but a way of reminding ourselves of the good and the true and the beautiful in the midst of lives which are all too often filled with quotidian concerns. It is definitely true that reading alone cannot make a whole man. But I do argue that this kind of fiction is an important part of attaining the sound mind part of mens sana in corpore sano.

It would be far too strong a conclusion to say that Christians must read adventure fiction, but I think for the vast majority of men especially, adventure is entertainment that can be ordered to the good of your mind and supportive of your faith, if curated properly. From my experience, there is enough quality adventure fiction that meets that bar to last a lifetime. And my hope is that in some small way, I can make those stories better known.

Comments ()