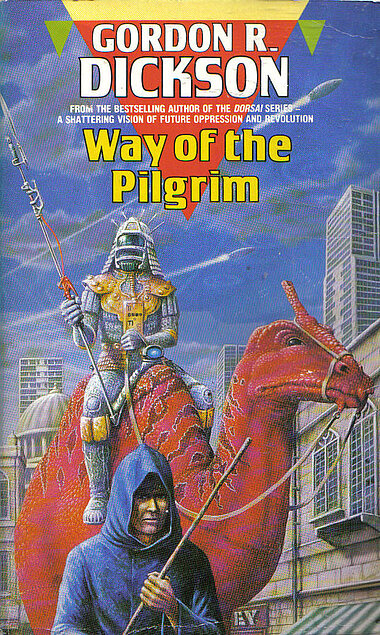

The Way of the Pilgrim

Way of the Pilgrim By Gordon R. Dickson $4.50; 439 pages

Way of the Pilgrim

By Gordon R. Dickson

$4.50; 439 pages

I came across Way of the Pilgrim by means of Jerry Pournelle's There Will Be War series. Chapter 2 of Way of the Pilgrim appears in Volume IV: Day of the Tyrant. I thought the story was intriguing enough to make it worth reading, and I was right.

Way of the Pilgrim is a good example of the value of hard sci-fi. The core of a good hard sci-fi story is built around some insight into how the world really works. Sometimes the plot is an afterthought to this, and sometimes not. This insight need not actually be from physics or engineering, although that is standard. The core insight in Way of the Pilgrim is all about language, and how hard it is to conceive things for which your language does not even have a word.

Way of the Pilgrim turns the typical sci-fi story on its head, both for its setting, the utter conquest and subjugation of humanity by a foe, the Aalaag, that is ridiculously superior, and for its relative uninterest in the technology of the conquerors, which is so advanced as to be indistinguishable from magic. Resistance really is futile. There will be no grand revolution of the oppressed masses. Merely eternal servitude.

While there is action and intrigue here, the real meat of the book centers on extensive dialogue and psychological deductions. Ultimately everything turns on a moral question. The problem the book posits: what is the value of a human being? The conquerors refer to us as cattle, because they are superior to us in every way: bigger, stronger, faster, smarter, healthier, longer-lived, more rational, more moral. The Aalaag are simply better than us, and they know it. The humans feel otherwise, but they have no ability to effectively protest. There are not even words to express the idea in the true language. The Aalaag do have a word, yowaragh, for the irrational failure of a beast to submit to its rightful master. Humans are exceptionally likely to suffer from this sickness.

The central drama of the protagonist's life is also moral. Shane Evert serves the commander of the Aalaag as an interpreter/courier, because of his unusual linguistic abilities that allow him to speak the Aalaag language. He enjoys great privilege from his position, as a favored pet might. Naturally, everyone else hates him for serving their indifferent masters. I would say cruel, but the Aalaag are too practical to be cruel. They will not waste good cattle unless they need to. However, they often need to, because humans persist in resisting their masters.

Shane tries his best to be indifferent, partly as a matter of survival, for the Aalaag expect their servants to be as stoic as they, but Shane cannot reconcile the objective superiority of his masters with an inchoate intuition of human dignity. He cannot help but care for the fate of his fellow humans. He commits his own act of yowaragh, sketching a hooded pilgrim beneath the corpse of a man executed for daring to challenge an Aalaag that nearly trampled his wife. Shane's act of rebellion does spark a worldwide revolution, which he finds himself drawn into against his will.

Shane initially wants to exploit this revolution for his own ends, because it is completely without hope of success, so he is looking to position himself for its inevitable failure. However, the intuition of human dignity that caused him to sketch the pilgrim also causes him to begin to love his fellow men for the first time in his life, and he seeks a way to actually drive the Aalaag from the planet.

The climax of the book leaves the tension between Aalaag and human unresolved. There is simply too little common ground to come to any kind of satisfactory resolution. The ending is quite startling in its refusal to settle the issue at hand. Perhaps even more interesting than the bleak setting and inconclusive conclusion is what remains unsaid throughout the book.

The Aalaag stand as a rebuke towards any instrumental view of human nature that seeks to define us as worthy of moral respect because of what we do rather than who we are. The Aalaag's view of humanity is disturbing because it is correct. The Aalaag really are superior to us. If what makes us worthy of respect is our behavior, or our consciousness, or our ability to make free choices, we have no hope of standing as equals. Yet, for all that, they are ultimately just as broken as we are. It is just less obvious from a modern point of view why this is so, because a clean, orderly, crime-free, egalitarian society is what we all really want, right?

Comments ()