The Long View 2009-09-26: Jung in the 21st Century

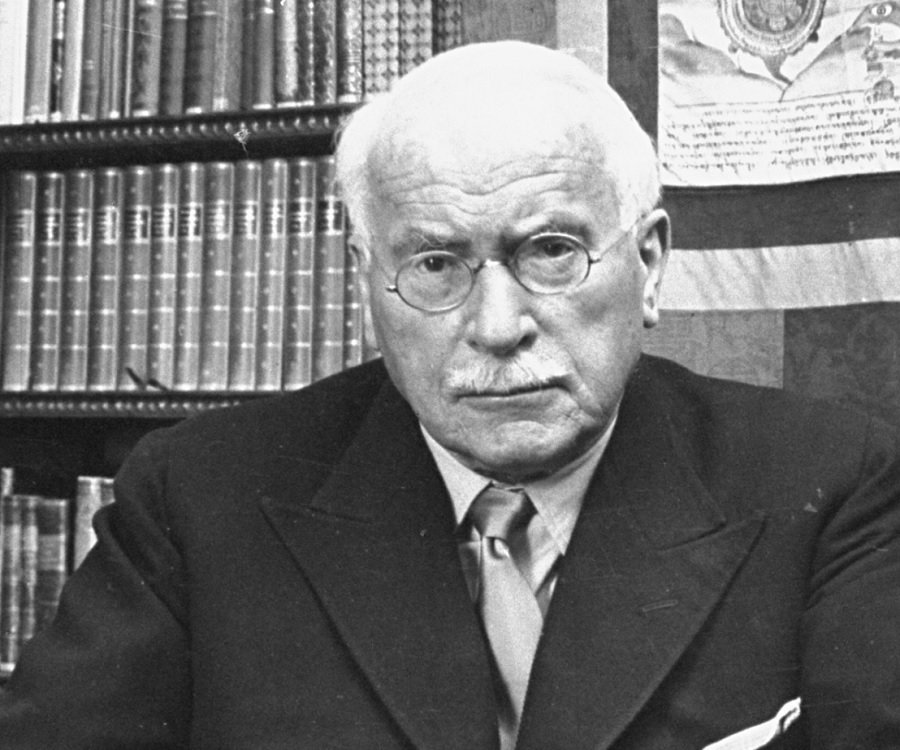

Carl Jung

It isn't at all clear that Carl Gustav Jung's reputation survived the publication of his most famous work, Liber Novus, known as the Red Book. Both John Reilly and Tim Powers have made use of his ideas, but the sheer strangeness of the work makes it uninteresting to the prosaic and political twenty-first century.

Jung in the 21st Century

When I was in college, I read my way through most of Carl Gustav Jung's Collected Works, in the elaborately illustrated and suitably dark hardcover volumes issued by the Bollingen Foundation. I by no means regard the time spent as wasted; you can get a good education just acquiring the resources to understand a system like Jung's. Neither do I condescend to Jungians with the attitude that Jung's philosophy is just something you outgrow; there are many unfootnoted Jungian notions floating around in my published work. Still, I don't think there was ever a time when I confused Jungianism with enlightenment, much less with salvation (people who knew me 35 years ago may remember otherwise, but if so, their memories are defective).

In any case, the Bollingen Foundation no longer exists. They decided in the 1960s that their work of making Jung's principal works available was complete and they turned the Bollingen Series over to Princeton University Press. Smaller entities have continued to promote Jung's works and ideas, however. Among them is the Philemon Foundation, which is about to strike a publishing coup:

During WWI, Jung commenced an extended self-exploration that he called his "confrontation with the unconscious." During this period, he developed his principal theories of the collective unconscious, the archetypes, psychological types and the process of individuation, and transformed psychotherapy from a practice concerned with the treatment of pathology into a means for reconnection with the soul and the recovery of meaning in life. At the heart of this endeavor was his legendary Red Book, a large, leather bound, illuminated volume that he created between 1914 and 1930, and which contained the nucleus of his later works. While Jung considered the Red Book, or Liber Novus (New Book) to be the central work in his oeuvre, it has remained unpublished...

Unpublished until October of this year, when a carefully produced facsimile edition with a critical (as in "annotated") English translation from the German will appear.

In some ways, the Red Book, as it will be called, sounds a bit like the Hypnerotomachia Poliphili, which is also a heavily illustrated expression of the “active imagination”:

([I]n English Poliphilo's Strife of Love in a Dream, from Greek hypnos, "sleep", eros, "love", and mache, "fight") is a romance by Francesco Colonna and a famous example of early printing. First published in Venice, 1499, in an elegant page layout, with refined woodcut illustrations in an Early Renaissance style, Hypnerotomachia Poliphili presents a mysterious arcane allegory in which Poliphilo pursues his love Polia through a dreamlike landscape, and is at last reconciled with her by the Fountain of Venus.

(We know that Aldus Manutius published the work, by the way, but there is more than one view about authorship. Samples of the work are available at that link, too.)

Despite the parallels, the Hypnerotomachia Poliphili seems to be different in kind from the Red Book. For one thing, the former is a carefully constructed work designed in part to show off the author's Classical erudition. By all accounts, the Red Book is dense with obscure references, too, but only incidentally. The author was deliberately trying not to construct the book, but to let his imagination function without editing. There is also this: the book is fascinating, in the special sense of mesmerizing or bewitching, to Jungians and to people interested in related subjects. That is certainly the impression created by Sara Corbett's long article in the September 20 issue of the New York Times Magazine on the upcoming publication of the Red Book, The Holy Grail of the Unconscious. To some extent, the fascination adheres to the physical book itself, for so many years just an illuminated rumor in a bank vault. The book does have text, however:

Jung says: "I too believe that I've completely lost myself. Am I really crazy? It"s all terribly confusing."

The professor responds: "Have patience, everything will work out. Anyway, sleep well."

Two items in Jung's box of tricks seem particularly responsible for keeping spiritual seekers interested in the system, for the excellent reason that these items resonate in the seekers' experience. One is that, if you pay attention to your dreams, they really will put on a show for you, though one may question whether the performance reliably follows the depth-psychological script or means quite what the depth-psychologists say. The other attraction is "synchronicity," the phenomenon of the "significant coincidence." Again, if you look for synchronous events, you will surely find them. If you are at all philosophically minded, you will spend many happy hours trying to figure out whether the coincidences are real or just a product of selective attention, or whether that distinction can have any meaning. And look, here is a synchronous event right here, since the very day the New York Times piece appeared (though before I read it or heard rumor of it, I solemnly swear) I posted to my website a long review of Frank McLynn's biography of Marcus Aurelius, which contains this passage:

The author brings some interests to this study that are peculiarly relevant to the period, but that some early 21st-century readers may find as exotic as the gladiatorial games that Marcus found so tedious. The author is keenly interested in depth psychology, particularly of the Jungian variety, which really was prefigured in the medicine of the second century. The famous second-century oneirologist Artemidorus gets several mentions (he is not very obscure, since he influenced both Jung and Freud). For that matter, so does the deified Asclepius, who offered advice in dreams to both physicians and patients; this was a culture in which valetudinarianism seems almost to have been a spiritual discipline.

Robertson Davies, himself a Jungian of the strict observance, attempted in The Cunning Man to describe an internist's medical practice that employed such a model. Regarding the second century, Peter Brown has noted that the Antonine Age enjoyed, or at least experienced, a low-key but personally important spiritual life that involved access to the numinous through dreams; and one might add, through the affect associated with holy places. However, we should remember that, even centuries earlier when pure theory preoccupied the finest minds of the Classical world, the ancients meant by the term "philosophy" something very like what Jungians mean by Jungianism: not just a system of propositions, but a therapeutic regimen with a comprehensive intellectual component.

On the whole, it seems to me that there are two things to remember about Jungianism. The first, which the Jungians themselves urge, is that their system may be good for you but it is not really “medicine.” The second is that Jungianism is not a religion, though it functions as one for many of its adherents. It some respects, it seems to have been designed to make possible a spiritual life without a transcendent dimension. This would be as much a mistake in the twenty-first century as it was in the second.

* * *

Speaking of Jung, Hermann Hesse was a fan, but he seems to have come to the conclusion that Jungianism was a self-referential exercise, a sort of game of symbols. Am I the first person to whom it has occurred that the annual Eranos Conferences in Switzerland, with their gatherings of "psychologists, philosophers, theologians, orientalists, historians of religions, ethnologists, Indologists, Islamists, Egyptologists, mythologists and scientists" (and senior CIA officials, but don't get me started) was the model for the annual Glass Bead Game in Hesse's book of the same title?

Copyright © 2009 by John J. Reilly

Comments ()