The Long View: Omens of Millennium: The Gnosis of Angels, Dreams, and Resurrection

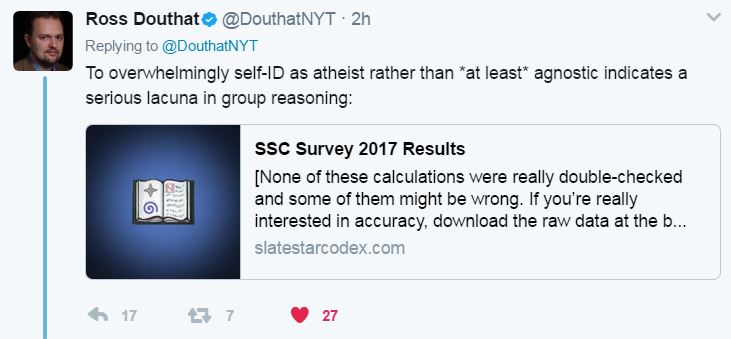

Ross Douthat pointed out today that atheism, as such, isn't particularly rational. For most of recorded history, gnosticism has been the preferred alternative for intellectuals to classical monotheism or paganism. The argument that God is evil is a far stronger one than that God doesn't exist.

Also, this paragraph:

Gnosticism

The short answer to this view is that apocalypse and gnosis usually go together. Certainly they did in Zoroastrianism, the apparent source of much of Judeo-Christian apocalyptic. It is common in religious systems for eschatology to be expressed on both the personal and the universal level. In other words, the fate of the world and the fate of individual human souls tend to follow parallel patterns, and Gnostic theology is no different. Manicheanism, for instance, had a particularly elaborate cosmology describing how the divine substance was trapped in the world of matter, forming the secret core of human souls. The hope Manicheanism offered was that someday this divine essence will all be finally released in a terminal conflagration. Details vary among Gnostic systems, but they generally hold that the creation of the world shattered God. History and the world will end when the fragments are reassembled. Often this takes the form of the reintegration of the Primal Adam, the cosmic giant whose fragments are our souls. While this aspect of gnosis can also be taken metaphorically, the fact is that Gnostic millenarianism has not been at all rare in history.

is the best summary of End of Evangelion I've ever seen. Far better than this psychoanalytic take [Freud was a fraud, dammit].

Omens of Millennium: The Gnosis of Angels, Dreams, and Resurrection

By Harold Bloom

Riverhead Books (G.P.Putnam's Sons), 1996

$24.95, pp. 255

ISBN: 1-57322-045-0

Getting Over the End of the World

Harold Bloom, perhaps, needs no introduction. A professor at both Yale and New York University, he is primarily a Shakespearean scholar who in recent years has taken an interest in religious questions in general and American religion in particular. This book is a personal spiritual meditation. Though quite devoid of index, footnotes or bibliography, it is well-informed, and the author is good about citing his sources. In fact, the book has something of the appeal of G.K. Chesterton’s historical works: the author relies on a modest selection of books with which many of his readers are probably familiar, so the argument is not intimidating. Reading it, you will learn a great deal about Sufism, Kabbalah and those aspects of popular culture that seem to be influenced by the impending turn of the millennium. You will, however, learn less about millennial anticipation than you might have hoped. The lack is not an oversight: apocalypse is a kind of spirituality that holds little appeal for Bloom. While this preference is of course his privilege, it does mean that, like the mainline churches which prefer to take these things metaphorically, his understanding of the spiritual state of today’s millennial America has a major blind spot.

Bloom's subject is his experience of "gnosis," the secret knowledge that is at once self-knowledge and cosmic revelation. The book's method is a review of different kinds of gnosis. Bloom has much to say about "Gnosticism" properly so-called, which was the religion of heretical Christians and Jews in the early centuries of the Christian era. (It would be churlish to put "heretical" in quotations marks here. The word, after all, was coined with the Gnostics in mind.) He is also concerned with contemporary popular spiritual enthusiasms. We hear a lot about the fascination with angels, dreams, near-death experiences and intimations of the end of the age that take up so much shelf-space in bookstores these days. Bloom is at pains to show that these sentimental phenomena in fact are part of a long Gnostic tradition that has engaged some of the finest minds of every age.

This aspect of the book is perhaps something of a patriotic exercise, since Bloom reached the conclusion in his study, "The American Religion," that America is a fundamentally Gnostic country, whose most characteristic religious product is the Church of Latter Day Saints. Bloom’s conclusions struck many people familiar with the professed theologies of America’s major denominations as a trifle eccentric, but he was scarcely the first commentator to claim that the people in the pews actually believe somthing quite different from what their ministers learned at the seminary. Besides, Tolstoy thought much the same thing as Bloom about the place of the Mormons in American culture, so who will debate the point?

Bloom is perfectly justified in complaining that the angels in particular have been shamefully misrepresented in America today. In the popular literature of angels, they appear as a species of superhero. They friendly folks just like you and me, except they are gifted with extraordinary powers to make themselves helpful, especially to people in life-threatening situations. Angels in art have been as cute as puppies for so long that the popular mind has wholly lost contact with the terrifying entities of Ezechiel’s vision. Bloom seeks to reacquaint us with these images, particularly as they have survived in Kabbalah and in Sufi speculation. He is much concerned with Metatron, the Angel of America, variously thought to be the Enoch of Genesis and the secret soul of the Mormon prophet Joseph Smith. His treatment of Metatron never quite rises to that of Neil Gaiman and Terry Pratchett in their novel, “Good Omens,” who describe him as, “The Voice of God. But not the ‘voice’ of God. A[n] entity in its own right. Rather like a presidential spokesman.” Nevertheless, it is good to see some hint of the true depths of angelic theology make available to the general public.

While “Omens of Millennium” is not without its entertaining aspects for people who do not regularly follow New Age phenomena, Bloom does seek to promote a serious spiritual agenda. The central insight of gnosis (at least if you believe Hans Jonas, as Bloom does without reservation) is the alienage of man from this world. We are strangers to both matter and history. Bloom despairs of theodicy. Considered with an objective secular eye, the world is at best a theater of the absurd and at worst a torture chamber. If there is a god responsible for this world, then that god is a monster or a fool. And in fact, for just shy of two millennia, Gnostics of various persuasions have said that the god of conventional religion was just such an incompetent creator. The consolation of gnosis is that there is a perfect reality beyond the reality of the senses, and a God unsullied by the creation of the world we know. The fiery angels, the prophetic dreams, the visions of an afterlife that make up much of the occult corpus are images of that true reality. They move in a middle realm, connecting the temporal and the eternal, ready to guide human beings desperate enough to seek the secret knowledge that gives mastery over them.

The people take these images literally. They believe they will not die, or that the resurrection is an event that will take place in the future. They believe that spiritual entities wholly distinct from themselves love them and care for them. They wait, sometimes with anxiety and sometimes with hope, for the transformation of this world. The Gnostic elite, in contrast, knows that these things are symbols. They understand that there is something in themselves that was never created, and so can never die. They can learn to use the images of the mid-world to approach these fundamental things, but without investing them with an independent reality. They need neither hope nor faith: they know, and their salvation is already achieved.

All of this sounds wonderfully austere. It allows for an aesthetic spirituality that avoids the twin perils of dead-between-the-ears materialism and vulgar supernaturalism. It is, one supposes, this sort of sensibility that accounts for the popularity of chant as elevator music. Neither is this spirituality without formidable literary exponents. Robertson Davies, for instance, suffused his fiction for decades with a genial Gnostic glow, marred only occasionally by a flash of contempt for the “peanut god” of the masses. Of even greater interest to Bloom, perhaps, would be the fiction of John Crowley. His recent novel, “Love and Sleep,” is entitled with the esoteric terms for the forces by which the truly divine is imprisoned in the world of matter. The story even treats in large part of Shakespeare and Elizabethan England, Bloom’s special province. If gnosis as such still seems to have a relatively small audience, this could be reasonably ascribed to its very nature as a philosophy for a spiritual elite. The problem with Bloom’s particular take on gnosticism, however, is that it is not only alien to sentimental popular religion, it is also alien to the esoteric forms gnosis has taken throughout history.

Bloom believes that gnosis appears when apocalyptic fails. This is what he believes happened in Judaism around the time of Jesus. By that point, Palestine had been bubbling with literal millenarianism for two centuries. Generation after generation looked for the imminent divine chastisement of Israel’s enemies and the establishment of a messianic kingdom. This universal regime would endure for an age of the world that, thanks to the Book of Revelation, finally came to be called “the millennium.” The dead would rise, the poor would be comforted, and the wicked would be infallibly punished. It was the stubborn refusal of these things to happen that prompted the strong spirits of those days to consider whether they may not have been looking for these things on the wrong level of reality. They were not arbitrary fantasies; they spoke to the heart in a way that mere history could not. Rather, they were images of realties beyond what this dark world could ever support. This was true also of the image of the apocalypse, in which this world comes to the end it so richly deserves. Apocalypse properly understood is not prophecy, but an assessment that put this world in its place. More important, it pointed to the greater reality that lay eternally beyond the world. Bloom hints that this process of ontological etherealization is in fact the explanation for Christianity itself, since he suspects that Jesus himself was a Gnostic whose subtle teachings were grossly misinterpreted by the irascible apostle Paul.

The short answer to this view is that apocalypse and gnosis usually go together. Certainly they did in Zoroastrianism, the apparent source of much of Judeo-Christian apocalyptic. It is common in religious systems for eschatology to be expressed on both the personal and the universal level. In other words, the fate of the world and the fate of individual human souls tend to follow parallel patterns, and Gnostic theology is no different. Manicheanism, for instance, had a particularly elaborate cosmology describing how the divine substance was trapped in the world of matter, forming the secret core of human souls. The hope Manicheanism offered was that someday this divine essence will all be finally released in a terminal conflagration. Details vary among Gnostic systems, but they generally hold that the creation of the world shattered God. History and the world will end when the fragments are reassembled. Often this takes the form of the reintegration of the Primal Adam, the cosmic giant whose fragments are our souls. While this aspect of gnosis can also be taken metaphorically, the fact is that Gnostic millenarianism has not been at all rare in history.

One of the impediments to understanding apocalyptic is the secular superstition, perhaps best exemplified by E.J. Hobsbawm’s book “Primitive Rebels,” that millenarianism is essentially a form of naive social revolution. Thus, one would expect people with an apocalyptic turn of mind to be ill-educated and poor. Bloom is therefore at something of a loss to explain the ineradicable streak of millenarianism in American culture, a streak found not least among comfortable middle class people who worship in suburban churches with picture windows. His confusion is unnecessary. Indeed, once could argue that the persistence of American millenarianism is some evidence for his thesis that America is a Gnostic country, since gnosticism is precisely the context in which apocalyptic flourishes among the world’s elites.

Sufi-influenced Islamic rulers, from the Old Man of the Mountain to last Pahlevi Shah of Iran, have a long tradition of ascribing eschatological significance to their reigns. Kabbalah has an explosive messianic tradition that has strongly influenced Jewish history more than once, most recently in the ferment among the Lubavitchers of Brooklyn. (The tradition is itself part of an intricate system of cosmic cycles and world ages, in which more or less of the Torah is made manifest.) Regarding Christian Europe, Norman Cohn has made a special study of the Heresy of the Free Spirit, which from the 13th century forward offered Gnostic illumination to the educated of the West in a package that came with the hope of an imminent new age of the spirit. As Bloom knows, the Renaissance and early modern era, and not least Elizabethan England, was rife with hermeticists like Giordano Bruno who divided their time between political intrigue and their own occult apotheosis. The gentlemanly lodge-politics of the pre-revolutionary 18th century made a firm connection between hermetic theory and the hope of revolution (as well as providing endless entertainment for conspiracy buffs who think that secret societies like the Bavarian Illuminati are somehow immortal). Whatever else can be said about gnosis, it is clearly not hostile to apocalyptic thinking.

In the light of this history, it is hard to accept Bloom’s complacent assertion that gnosis bears no guilt because it has never been in power. It has frequently been in power, though rarely under its own name. There is even a good argument to be made that the Nazi regime was fundamentally Gnostic. Certainly Otto Wagoner, one of Hitler’s early confidants, made note of his master’s admiration for the Cathars, those martyrs of the Gnostic tradition. Some segments of the SS even cultivated Vedanta. For that matter, as Robert Wistrich argued in “Hitler’s Apocalypse,” the regime’s chief aim was the expungement of the Judeo-Christian God from history. Marcion, the ancient heresiarch who rejected the Old Testament as the work of the evil demiurge, might have been pleased.

Is there a logical connection between gnosis and apocalyptic? Of course. Apocalypses come in various flavors. Some are hopeful, some are fearful, some are actually conservative. There is also an apocalypse of loathing, of contempt and hatred for the world and its history. We can clearly see such a mood in societies that nearly destroy themselves, such as Pol Pot’s Cambodia, or sixteenth century Mexico, but to a smaller degree it has also informed less extreme revolutions and upheavals throughout history. Gnosis has much in common with this mood. Gnostics at best seek to be reconciled with the world. Some seek to purify themselves of it. Others look forward to its destruction in a grossly literal fashion. More than a few, it seems, have been willing to help the process along.

Finally, at the risk of making a churlish comment about what after all is supposed to be a personal spiritual statement, one might question the credentials of gnosis to be the treasured possession of a true spiritual elite. Bloom mentions at one point that C.S. Lewis’s “Mere Christianity” is one of his least favorite books. One may be forgiven for wondering whether this antipathy arises because even a cursory acquaintance with Lewis’s writings show him to have been a Gnostic who eventually grew out of it. (If you want a popular description of serious angels, no book but Lewis’s novel “That Hideous Strength” comes to mind.) As St. Augustine’s “Confessions” illustrates, gnosis may be a stage in spiritual maturity, but it has not been the final destination for many of the finest spirits. Bloom seems to think that his version of gnosis has a great future in the next century, after people tire of their current millennial enthusiasms. Perhaps some form of spirituality has a great future, but it is unlikely to be the one he has in mind.

An abbreviated version of this article appeared in the February 1997 issue of First Things magazine.

Copyright © 1997 by John J. Reilly

Omens of the Millennium: The Gnosis of Angels, Dreams, and Resurrection By Harold Bloom

Comments ()