The Long View 2004-08-30: Victory, Law-and-Order, Peace

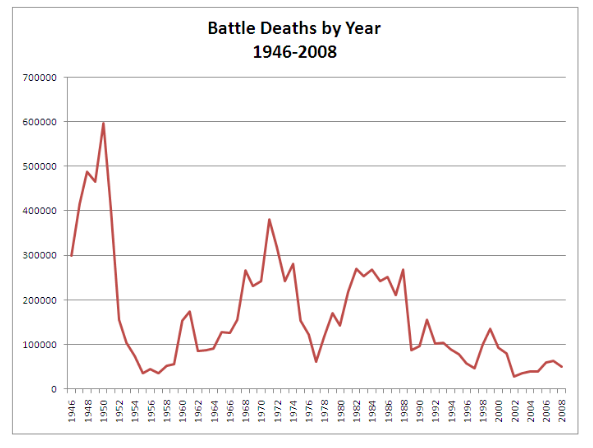

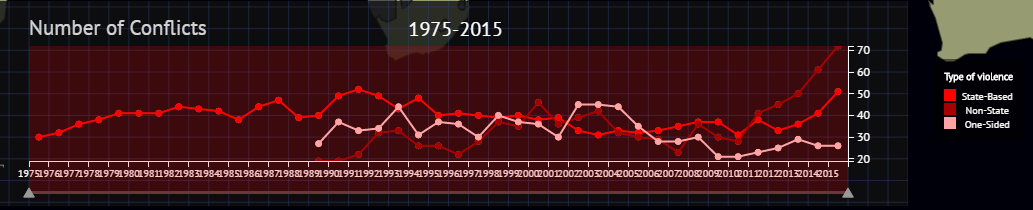

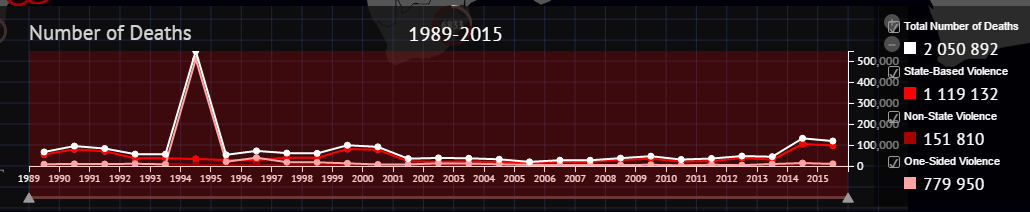

The rosy picture of human conflict John reported in this post from 2004, called Pinkerization after Steven Pinker's book The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined, no longer looks so good. As late as 2008, the data from the Uppsala Conflict Data Program looked much the same as it did in 2004, but in 2017 things are looking considerably worse.

Number of Conflicts

Number of Deaths

Neither of the graphs above would be discernable if the axis extended back to WWII. Compared to that, everything else is just noise. Hopefully, that trend will continue.

Victory, Law-and-Order, Peace

Over the weekend, PBS broadcast the classic political film, The Candidate. Though it premiered in 1972, it has aged remarkably well. The scary thing, in fact, is that one or two of the journalists who are mentioned in the film are still in business.

The movie is about a young, liberal Californian public interest lawyer named Bill McKay (played by Robert Redford), who is prevailed upon by a political consultant to run for the U.S. Senate. His Republican opponent is a pompous old incumbent named Crocker Jarmon (played by Don Porter). McKay, though the son of a former governor, has no political ambitions. However, he is energized to run when he goes to a Jarmon rally and hears his reactionary program: welfare reform; the accommodation of environmental regulation to the needs of economic growth; pro-life; reflexive patriotism.

I saw The Candidate when it first came out, and like everyone else, I liked it then. Like most people at the time, I also hummed along with McKay's politics. What is shocking after all these years is how completely Jarmon's ideas have become the dynamic ones. Today, a candidate as young as McKay, and sporting the same kind of golden-helmet haircut, would almost certainly be delivering Jarmon's stump speech.

* * *

Speaking of dynamic ideas, The New York Times Magazine yesterday tried to offer the Republican Party a few, in an article entitled How to Reinvent the G.O.P. The piece was by David Brooks, a Republican but a social liberal, whom the Times keeps as a columnist so the paper can pretend it has an ideologically inclusive editorial page.

The article deals with the same problem that Ralph Reed grappled with in his 1996 memoir, Active Faith: the Republican Party came to power as an opposition coalition that had few concrete ideas about governing. Even in the mid-1990s, it was absurd to for Congress to be run by a party with only negative ideas about domestic governance and no ideas at all about foreign affairs. Today, of course, it's lunacy. Fortunately, Brooks tells us:

[Some Republicans are] at least trying to come up with a governing philosophy that applies to the times. [They understand] the paradox that if you don't have a positive vision of government, you won't be able to limit the growth of government.

Chief among these is George Bush himself, whose platform in 2000 did in fact contain proposals in addition to tax cuts. Brooks, and the folks at the Weekly Standard, want to push the Republican agenda in the direction of what, before 911, they called "National Greatness," but which now they call Hamiltonian Progressive Conservatism. The argument for this is backed up by a retelling of American history that highlights the economic and social policies of Abraham Lincoln and Theodore Roosevelt.

This is good enough, as far as it goes, but there is a solid nugget of dissimulation in Brooks's outline for an entitlements policy that could ensure that the Republicans never become a real majority party:

The solution is clear: push back the retirement age, reduce benefits for upper-income people, redesign the welfare state so that individuals have control over their own benefits packages. That means designing programs that allow people to have their own health insurance, which they can carry from job to job; to control their own unemployment insurance and tailor their retraining efforts to suit their own talents; to invest part of their own pension money and benefit from higher returns, so they have greater incentives to save on their own. It means reforming the health care system so competition works as it does in every other sphere -- to improve value, spur innovation and reduce costs.

People don't want more choices about health insurance and Social Security. I suspect that most of us have gathered by now that foundations that promote "reproductive choice" are less interested in expanding the sphere of choice than in limiting reproduction. In the context of support for the old and the sick, this verbal gimmickry will quickly become both obvious and intolerable.

There are two points to keep in mind about entitlement reform:

--If the US economy is not producing enough tax revenue to pay Social Security benefits, it will not be producing enough interest or dividends to do so, either.

--Health care is a question of basic public order, like police and fire services. Elements of the system can be private, but "choice" can never be a fundamental consideration.

* * *

Evidence is trickling in that the Millennium really did begin when the millennium began:

In fact, the number killed in battle has fallen to its lowest point in the post-World War II period, dipping below 20,000 a year by one measure. Peacemaking missions, meantime, are growing in number...A collaboration with Sweden's Uppsala University, [the 2004 Human Security Report] will conservatively estimate battle-related deaths worldwide at 15,000 in 2002 and, because of the Iraq war, rising to 20,000 in 2003. Those estimates are sharply down from annual tolls ranging from 40,000 to 100,000 in the 1990s, a time of major costly conflicts in such places as the former Zaire and southern Sudan, and from a post-World War II peak of 700,000 in 1951.

That's encouraging, but then we have the chicken-or-egg question: does the UN create peace, or do peace agreements make work for the UN?

The recent record shows "conflicts don't end without some form of intervention from outside," said Renata Dwan, who heads the [Stockholm International Peace Research Institute] program on armed conflict and conflict management... The idea of U.N. primacy in world peace and security took a "bruising" at U.S. hands in 2003, when Washington circumvented the U.N. Security Council to invade Iraq, Dwan noted. But meanwhile, elsewhere, the world body was deploying a monthly average of 38,500 military peacekeepers in 2003 -- triple the level of 1999...By year's end, the institute yearbook will conclude, "the U.N. was arguably in a stronger position than at any time in recent years

Whatever else is going on, it is still the case that we live in a demilitarizing world:

According to the study, the value of all weapons transfer agreements worldwide was more than $25.6 billion in 2003, the third consecutive year that the dollar total for global arms deals declined. When measured in dollars adjusted for inflation to give an accurate comparison to the $25.6 billion figure, the value of global arms agreements has steadily fallen, from $41 billion in 2000.

One can only repeat that the activities of the United States are not an anomaly to this trend, but its predicate:

Fewer large-scale arms purchases were being made by the wealthier oil nations in the Middle East, whose earlier buying sprees contributed to a bull market in weapons when Iraq under Saddam Hussein was a regional threat. The report said it remained uncertain whether the Persian Gulf states would now perceive a potentially hostile Iran as a new motivation to improve their arsenals.

Copyright © 2004 by John J. Reilly

The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined By Steven Pinker

Comments ()